Temple Architecture Styles : Zhōngguó Free-standing Temple architecture

Zhōngguó free-standing temple architecture1 demonstrates an architectural style that developed over millennia in Zhōngguó region (core China region/proper excluding vassal states), before spreading out to influence architecture throughout East Asia. Since the solidification of the style in Early Imperial Period (c. 221 BCE – 589 CE) , the structural principles of Zhōngguó architecture have remained largely unchanged, the main changes being only the decorative details.

Starting with Táng dynasty (618 CE – 907 CE), Zhōngguó architecture had a major influence on architectural styles of Nihon, Joseon, and Vietnam, and a varying amount of influence on architectural styles of Southeast and South Asia including Malaysia, Singapore, Indonesia, Sri Lanka, India, Thailand, Laos, Cambodia and Philippines. Zhōngguó free-standing temple style roofing and halls were also adopted into Zhōngguó region’s rock-cut architecture.

Types of temples:

Zhōngguó architecture style temples can be classified on basis on religion which also dictates the construction methods and layout.

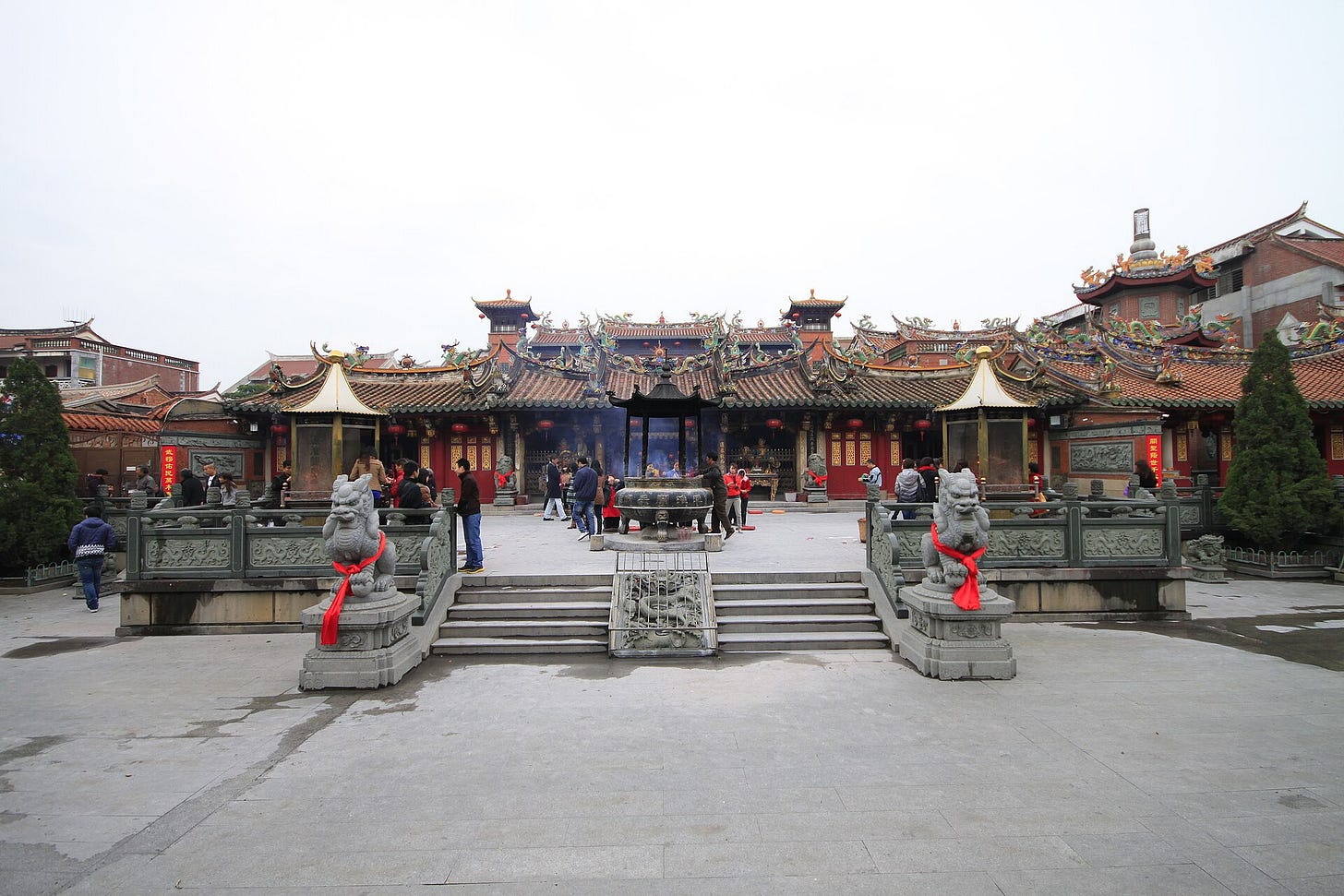

Miào (廟 ) or Diàn (殿) — mostly enshrines deities of the Zhōngguó folk pantheon like Lóng Wáng (Dragon King), Tudigong or Matsu, or mythical or historical figures, such as Guandi or Shennong

Chénghuáng Miào (城隍廟 ; Temple of City God) — worships the patron deity of a village, town or a city

Wén Miào (文廟) or Kŏng Miào (孔廟) — Rújiā Temple or Sòng-Míng lǐxué temple (actually a large temple complex) which usually functions as both temple and town school.

Wǔ Miào (武庙 ; military temple)2 — dedicated to worshiping outstanding military leaders and strategists (excluding kings and emperors). They were often built by the governments as the counterpart of civil temples (Wénmiào).

Wénwǔ Miào (文武廟 ; civil & military temple)3 — dual temple venerating both a Wéndì (文帝; civil deity) and a Wǔdì (武帝; martial deity) in same complex. In southern Zhōngguó the civil deity is Wénchāng while in the north it is Kǒng Qiū; in both areas the martial dety is Guān Yǔ.

Cí (祠), Cítáng (祠堂), Zōngcí (宗祠) or Zǔ Miào (祖廟 ) — ancestral temples, mostly enshrining the ancestral deities of a family or clan

Guàn (觀) or Dàoguàn (道觀) — Taoist temples and monasteries

Sì (寺) or Sìyuàn (寺院) — Zhōngguó Buddhist temples and monasteries

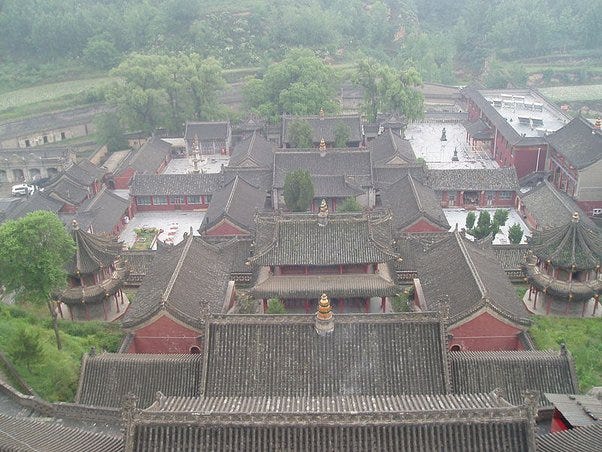

Generally speaking, Zhōngguó Buddhist architecture follows the imperial style i.e. architecture of palaces. A large Buddhist monastery normally has a front hall, housing the statues of Four Heavenly Kings, followed by a great hall, housing the statues of Buddhas. Accommodations for the monks and the nuns are located at the 2 sides. Buddhist monasteries sometimes also have pagodas, which may house the relics of Buddha; older pagodas tend to be 4-sided, while later pagodas usually have eight sides.

Taoist architecture usually follows the commoners' style i.e. architecture of common people’s homes. The main entrance is, however, usually at the side, out of superstition about demons which might try to enter the premise. In contrast to Buddhists, Taoist temple complex’s main deity is located in the main hall at the front, the lesser deities in the back hall and at the sides. This is due to Zhōngguó belief that even after the body has died, the soul is still alive. From the Hàn grave design, it shows the forces of cosmic yīn & yáng, the 2 forces from heaven and earth that creates eternity.

Development

Ancient Zhōngguó architecture has numerous similar elements in part, because of the early Zhōngguó method of standardizing and prescribing uniform features of structures. The standards are recorded in bureaucratic manuals and drawings that were passed down through generations and dynasties. These account for the similar architectural features persisting over thousands of years, starting with the earliest evidence of Zhōngguó imperial urbanism. The plans include, for example, 2D architectural drawings as early as 1st millennium CE, and explain the strong tendency for the shared architectural features in Chinese architecture, that evolved through a complicated but unified evolutionary process over the millennia. Generations of builders and craftsmen recorded their work and the collectors who collated the information into building standards (for example Yíngzào Fǎshì) and Qīng Architecture Standards were widely available, in fact strictly mandated, and passed down. The recording of architectural practice and details facilitated a transmission throughout the subsequent generations of the unique system of construction that became a body of unique architectural characteristics.

The most common building type had regularly spaced timber posts which were strengthened by horizontal cross-beams. To better protect the building from earthquake damage, very few nails were used, and joins between wooden parts were made to interlock using mortises and tenons which gave a greater flexibility. The wooden posts supported a thatch roof in earlier architecture and then a gabled and tiled roof with the corners gently curving outwards and upwards at the corners. By 3rd century CE hip and gable roofs became common.

2nd century BCE – 3rd century CE

Hàn Dynasty (202 BCE – 9 CE, 25 CE – 220 CE)4

Western Hàn (202 BCE – 9 CE)

Eastern Hàn (25 CE – 220 CE)

Polities:

Hàn dynasty was established by the rebel leader Liú Bāng and ruled by the House of Liú. It was briefly interrupted by Xīn dynasty (9 CE – 23 CE) established by the usurping regent Wáng Mǎng, and was separated into two periods — Western Hàn (202 BCE – 9 CE) and Eastern Hàn (25 CE – 220 CE) — before being succeeded by Three Kingdoms period (220 CE – 280 CE).

This was the first time when a Zhōngguó-based polity’s control extend to Xīyù5 (i.e regions west of Yumen Pass, primarily Tarim basin), which in turn laid the conditions of transmission of knowledge of Tarim region’s rock-cut caves into Zhōngguó. Xīyù Dūhù Fǔ (Protectorate of the Western Regions) consisted of various vassal states and Hàn garrisons placed under the authority of a protector-general of Western Regions, who was appointed by the Hàn court.

→ [Source: https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/0/08/Han_Dynasty_map_2CE.png]

Temples:

The use of Què gateways reached its peak during Hàn Dynasty.

With increased trade during Hàn dynasty and cultural exchanges through Silk road, lions were introduced into Zhōngguó from the ancient states of Central Asia by peoples of Sogdiana, Samarkand, and the Yuezhi in the form of pelts and live tribute, along with stories about them from Buddhist priests and travellers of the time. Buddhist version of the Lion was originally introduced to Hàn Zhōngguó as the protector of dharma and these lions have been found in religious art as early as 208 BCE. Gradually they were incorporated as guardians of Zhōngguó Imperial dharma. Lions seemed appropriately regal beasts to guard the emperor's gates and have been used as such since.

With spread of Buddhism, Helleno-Buddhist art also made its way into Zhōngguó. Some of the earliest known Buddhist artifacts found in Zhōngguó are small statues on "money trees", dated ~200 CE (Eastern Hàn period), in typical Gandharan style.

White Horse Temple Complex, Zhōngguó’s first Buddhist temple was originally constructed under Hàn dynasty. {It was reconstructed much later to its present state under Míng, Qīng and then present PRC governments}

In 205 BCE, emperor Liú Bāng became the first emperor to offer sacrifices to the memory of Kǒng Fūzǐ in Qufu. He set an example for many emperors and high officials to follow. Later, emperors would visit Qufu after their enthronement or on important occasions such as a successful war. This practice led to royal patronage to Confucianism as well, along with independent patronage to Buddhism.

3rd century CE – 7th century CE

Sānguó Shídài (Three Kingdoms period) (220 CE – 280 CE)

Six Dynasties Period (220 CE – 589 CE)

Jìn dynasty (266 CE – 420 CE)

Shíliù Guó (Sixteen Kingdoms period) (304 CE – 439 CE)

Nán běi cháo (Northern & Southern dynasties period) (386 CE – 589 CE)

Northern Wèi (Běi Wèi / Tuòbá Wèi) (386 CE – 535 CE)

This period saw many empires and kingdoms rise and fall, but a mostly politically fractured Zhōngguó until the rise of Táng dynasty.

By 6th century CE, Buddhism had spread with tremendous momentum throughout Zhōngguó: Zhōngguó culture was adjusting and adapting its traditions to include Buddhist worship.

Polities:

Hàn authority had begun to decline by 184 CE itself, and numerous warlords emerged during this period, of which 3 became the most powerful. Three Kingdoms period of 220 CE – 280 CE consisted of the reigns of Cáo Wèi (220 CE – 266 CE), Shǔ Hàn (221 CE – 263 CE) and Sūn Wú (222 CE – 280 CE).

Cáo Wèi was established in 220 by Cáo Pi, the son of Cáo Cāo, who was made the Duke of Wèi in 213 CE by the eastern Hàn government. By 249 CE, Sīmǎ Yì, the regent of Wèi state gradually consolidated power into the hands of Sīmǎ clan, making the later emperors largely puppets to them.

Jì Hàn (Junior Hàn) or Shǔ Hàn (Shǔ region’s Hàn) was a Hàn rump state formed by Hàn imperial family’s distant relative Liú Bèi. This kingdom was invaded and felled by Wèi state.

Sūn Wú was founded by Sūn Quan, formerly a Wèi vassal who declared independence in 222 CE.

→ [Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Three_Kingdoms_timelapse.gif]

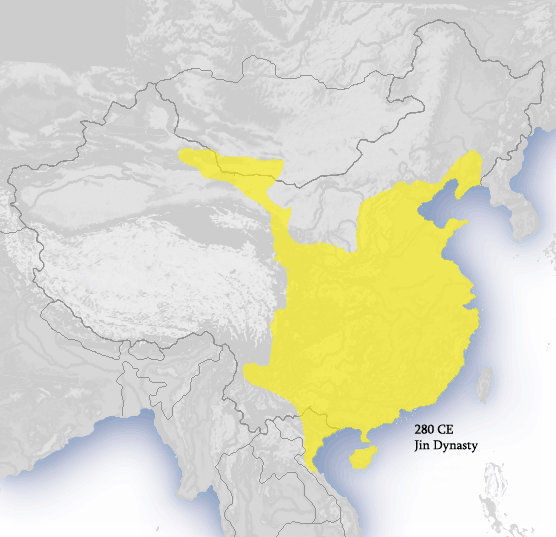

Jìn dynasty ended the Three Kingdoms period by their conquest of Sūn Wú, culminating in the reunification of Zhōngguó proper.

There are two main divisions in the history of the dynasty.

Western Jìn (266 CE – 316 CE) was established as a successor state to Early Wèi state after Sīmǎ Yán usurped the throne. It had its capital at Luoyang and later Chang'an (modern Xi'an, Shaanxi province, PRC). Western Jìn reunited Zhōngguó in 280 CE but fairly shortly thereafter fell into a succession crisis termed War of the Eight Princes, and suffered from the invasions instigated by the Non-Hàn ethnic Five Barbarians, who went on to establish various dynastic states along Huangho valley in 304 CE and successfully occupied northern Zhōngguó after Disaster of Yongjia in 311 CE. These states then immediately began fighting each other, inaugurating the chaotic and bloody Sixteen Kingdoms era.

After the fall of Chang'an in 316, Western Jìn dynasty collapsed, forcing survivors of the Jìn monarch under Sīmǎ Ruì to flee south of Yangtze to Jiankang (modern Nanjing) and establish Eastern Jìn (317 CE – 420 CE). Eastern Jìn dynasty, though under constant threats from the north, remained relatively stable for the next century, but was eventually usurped by general Liú Yù in 420 CE and replaced with Early Sòng (Liú Sòng) dynasty (420 CE – 479 CE). Western and Eastern Jìn dynasties together make up the second of Six Dynasties.

→ [Source: https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/9/9e/Western_Jeun_Dynasty_280_CE.png]

Sixteen Kingdoms period was a chaotic period in Zhōngguó history when the political order of northern Zhōngguó fractured into a series of short-lived dynastic states, most of which were founded by "Five Barbarians" - non-Hàn peoples who had settled in northern and western Zhōngguó during the preceding centuries and participated in the overthrow of Western Jìn dynasty in early 4th century CE. The kingdoms founded by ethnic Xiongnu, Xianbei, Di, Jie, Qiang, as well as Han and other ethnicities, took on Zhōngguó dynastic names, and fought against one another and Eastern Jìn dynasty. The period ended with the unification of northern Zhōngguó in early 5th century CE by Northern Wèi, a dynasty established by Xianbei Tuoba clan, and the history of ancient Zhōngguó entered Northern & Southern dynasties period.

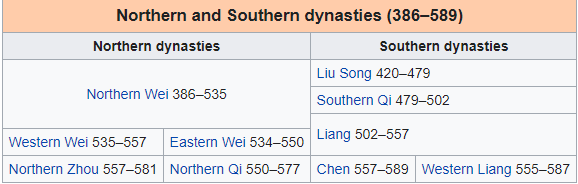

Northern and Southern dynasties was a period of political division in Zhōngguó’s history following the tumultuous era of Sixteen Kingdoms and Eastern Jìn.

→ List of Northern and Southern dynasties of the eponymous period [Source: screenshot from Northern and Southern dynasties - Wikipedia]

Temples:

Under Eastern Jìn Dynasty, Nanking Imperial University was established in first year of Sīmǎ Ruì’s reign (317 CE), initially on northern bank of Qinhuai River and later on, in 3rd year of Sīmǎ Yán (337 CE) the campus extended to southern bank. Temple of Confucius was firstly constructed in the national school in 9th year of Taiyuan (384 CE).

Several rulers of the northern kingdoms patronized Buddhism which spread across northern Zhōngguó during Sixteen Kingdoms and flourished during the subsequent Northern Dynasties.

Zhōngguó pagodas evolved during Northern and Southern dynasties period when Buddhism also started to become popular. The oldest extant Zhōngguó Buddhist pagoda is Songyue Pagoda in Dengfeng, Zhengzhou, Henan province, PRC built under Northern Wèi. It is a 12-sided tapering pagoda which seems to be an early attempt to merge Indian style stūpa architecture with traditional Zhōngguó architecture; later Zhōngguó pagodas have more traditional Zhōngguó forms — square, hexagon or octagon shape with little or no taper with height.

Members of the ruling family of Northern Wèi and Northern Zhōu constructed many of the caves of Mogao Cave complex (in Dunhuang, Gansu, PRC). These, and similar caves in Tarim basin region, are the precursors of Zhōngguó rock-cut architecture that later developed in Zhōngguó and then in Tarim basin itself.

Zushi Pagoda is a small funerary pagoda located in Foguang Temple complex (Wutai County, Shanxi Province of PRC) was either built during Northern Wèi Dynasty or Northern Qí Dynasty and possibly contains the tomb of the founder of Foguang Temple Complex.

→ Zushi Pagoda in Foguang Temple complex, Wutai County, Shanxi Province, PRC [Source: File:Foguang Temple 6.JPG - Wikimedia Commons]

Shíliù Guó (Sixteen Kingdoms period) (304 CE – 439 CE)

Several rulers of the northern kingdoms patronized Buddhism which spread across northern Zhōngguó during Sixteen Kingdoms and flourished during the subsequent Northern Dynasties.

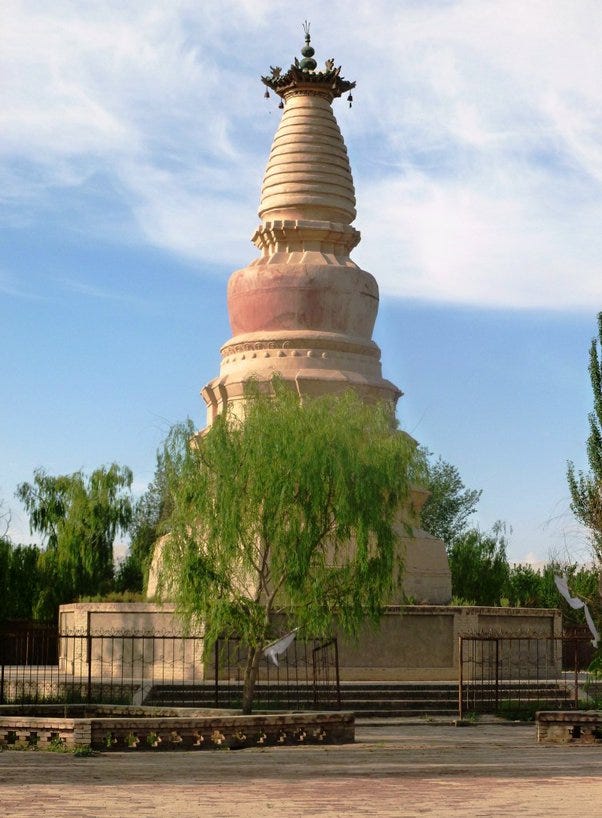

→ Böd style White Horse pagoda in Dunhuang, Gansu, PRC. Built ~384 CE under Fuqin kingdom [Source: File:White Horse Temple, Dunhuang.jpg - Wikimedia Commons]

Northern Wèi dynasty (386 CE – 535 CE) was the most long-lived and most powerful of the northern dynasties prior to the reunification of Zhōngguó by Suí dynasty. Northern Wèi art came under influence of Indian and Central Asian traditions through the mean of trade routes. Most importantly for Zhōngguó art history, Wèi rulers converted to Buddhism and became great patrons of Buddhist arts. Many antiques and art works, both Taoist art and Buddhist art, from this period have survived.

It was the time of the construction of Yungang Grottoes near Datong during mid-to-late 5th century CE, and towards the latter part of the dynasty, Longmen Caves outside the later capital city of Luoyang, in which more than 30,000 Buddhist images from the time of this dynasty have been found. Some of the caves of Western Thousand Buddha Caves and one cave of Five Temple Caves (in Subei Mongol Autonomous County, Gansu, northwest PRC) was also constructed under Norther Wèi.

Northern Wèi also constructed a Confucian temple in their capital in 489 CE, the first outside of Qufu in northern Zhōngguó.

→ A side-by-side image of Kaniṣka stūpa model [Source: File:Songyue Pagoda 1.JPG]

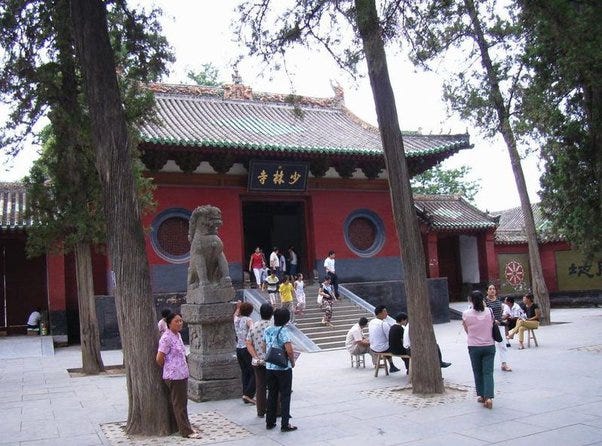

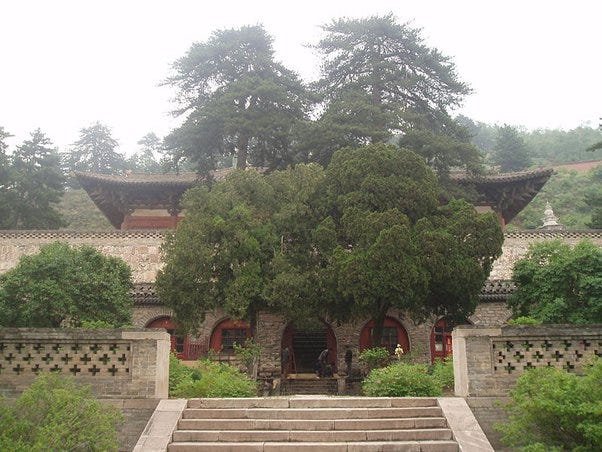

→ Shaolin Monastery was originally built under Northern Wèi [Source: File:少林寺.jpg - Wikimedia Commons]

Northern Qí (550 CE – 577 CE) ceramics mark a revival of Zhōngguó ceramic art, following the disastrous invasions and the social chaos of the 4th century CE. Markedly unique from earlier depictions of the Buddha, Northern Qí statues tend to be smaller, ~1m tall, and columnar in shape.

→ Northern Qí Bodhisattva, Changzi-xian, Shanxi province, PRC (dated 552 CE) [Source: File:NorthernQiBuddha.JPG - Wikimedia Commons]

7th century CE – 10th century CE

Táng dynasty (618 CE – 690 CE, 705 CE – 907 CE)

Polities:

The Lǐ family founded the Táng dynasty, seizing power during the decline and collapse of Suí dynasty and inaugurating a period of progress and stability in the first half of the dynasty's rule.

Temples:

The normal construction material for buildings other than towers, pagodas, and military works in the Táng was still wood, which does not survive very long if not maintained. The rock-cut architecture of the famous surviving sites of course survives neglect far better, but the Chinese generally left the external facades of cave-temples unornamented. Wood was originally utilised as a primary building material because it was very common. Also, Chinese people believe that life is connecting with nature and humans should interact with animated things, therefore wood was favoured as opposed to stone, which was associated with the homes of the dead. However, unlike other building construction materials, old wooden structures often do not survive because they are more vulnerable to weathering and fires and are naturally subjected to rotting over time.

The Buddhist art of Central Asia, particularly the area of Afghanistan, in the 7th-8th century CE shows a phase using "Sinicized Indian models". During this period, Táng Empire extended its influence and promotion of Buddhism to the polities of Central Asia, with a corresponding influx of Chinese monks, while there was conversely a migration of Indian monks from India to Central Asia, precisely looking for this protection. These events gave rise to the hybrid styles of Fondukistan and of the second artistic phase of Tapa Sardar in Afghanistan.

In 630 CE, Táng dynasty decreed that schools in all provinces and counties should have a Confucian temple, as a result of which such temples spread throughout Zhōngguó. Beginning with the Táng dynasty, Confucian temples were built in prefectural and county schools throughout the empire, either to the front of or on one side of the school.

In mid-8th century CE, Táng dynasty founded White Cloud Temple Complex in Beijing, PRC — the complex is one of "The Three Great Ancestral Courts" of the Quanzhen School. {the complex was completed under Míng dynasty}.

→ Great Buddha Hall of Nanchan Temple Complex in Wutaishan, Shanxi province, PRC. The Great Buddha Hall is the oldest preserved timber building extant in Zhōngguó, being built in 782 CE. [Source: File:Nanchan Temple 1.JPG]

→ Great East Hall of Foguang Temple Complex in Wutaishan, Shanxi province, PRC (Built 857 CE) [Source: File:Foguang Temple 9.JPG - Wikimedia Commons]

While stone and brick architecture is known to have been used in subterranean tomb architecture of earlier dynasties, from Táng dynasty onwards, brick and stone architecture gradually became more common and replaced wooden edifices, example being Xumi Pagoda built in 636 CE. While stone and brick buildings started appearing much later, many of the oldest surviving structures are stone structures due to the material’s durability.

→ Xumi Pagoda of the Buddhist Kaiyuan Monastery, Hebei province, PRC. It shows one of the forms common with Chinese Buddhist pagodas — a square floor-plan with little taper with height. (Built 636 CE) [Source: File:Xumi Pagoda 1.jpg]

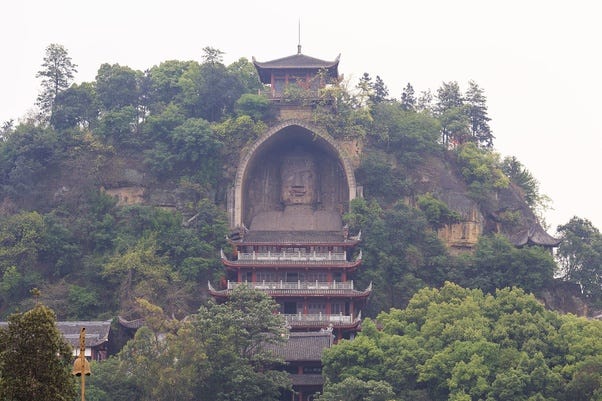

→ Róngxìan Giant Buddha carved out of the cliff face of a stone hill that lies to the north east of Rongxian and the Rongxi River in the eastern part of Sichuan province, south-eastern PRC (~ 817 CE; Táng dynasty) [Source: File:Rongxian Dafo 2014.04.24 14-18-42.jpg - Wikimedia Commons]

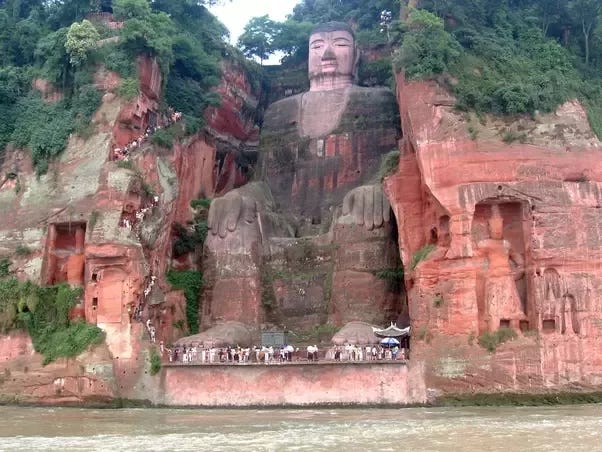

→ Leshan Giant Buddha near Leshan, Sichuan province, south-eastern PRC — At 71m height, it is the largest and tallest stone Buddha statue in the world. The statue was covered with a huge 13-storey wood structure, similar to the later Róngxìan Giant Buddha, to shelter it from rain and sunshine but that was destroyed during Yuán-Míng wars. (713-803 CE; Táng dynasty) [Source: File:Leshan Buddha Statue View.JPG - Wikimedia Commons]

10th century CE – 14th century CE

Five Dynasties & Ten Kingdoms period (907 CE – 979 CE)

Liáo dynasty (916 CE – 1125 CE)

Later Sòng dynasty (960 CE – 1279 CE)

Dà Xià dynasty (1038 CE – 1227 CE)

Jīn dynasty (1115 CE – 1234 CE)

Yuán dynasty (1271 CE – 1368 CE)

Five Dynasties & Ten Kingdoms period was an era of political upheaval and division in 10th-century CE Imperial Zhōngguó. It refers to 5 states in northern Zhōngguó and 10 states in southern Zhōngguó. Five states quickly succeeded one another in Central Plains (Zhōngyuán), and more than a dozen concurrent states were established elsewhere, mainly in southern Zhōngguó. Many states had been de facto independent kingdoms long before 907 CE as Táng dynasty's ability to control its officials gradually waned, but by this point, they had now been recognized as such by foreign powers.

Central Plains polities —

After the Táng had collapsed, warlords who controlled the Central Plains crowned themselves as emperors. During the 70-year-long period, there was near constant warfare between the emerging kingdoms and alliances they formed. All had the ultimate goal of controlling the Central Plains, which would have granted legitimacy over currently held territories and the rest of Zhōngguó as Táng’s successor. All the states were later conquered by Sòng Empire which ended this period.

Southern polities —

Unlike the dynasties of northern Zhōngguó, which succeeded one another in rapid succession, the regimes of southern Zhōngguó were generally concurrent, each controlling a specific geographical area. These were known as "Ten Kingdoms" (in fact, some claimed the title of Emperor, such as Wang Shǔ and Meng Shǔ). Each court was a centre of artistic excellence. The period is noted for the vitality of its poetry and for its economic prosperity.

→ Baochu Pagoda in Hangzhou, Zhejiang province, PRC. It is a stone pagoda lacking any eaves. Built 963 CE by Wúyuè state (907 CE – 978 CE) [Source: File:BaoChuTa.jpg - Wikipedia]

Liáo Empire, officially Dà Liáo (Great Liáo), Khitan Empire or Khitan (Qidan) State, was an empire and imperial dynasty in East Asia that ruled during 916–1125 CE over present-day Northern and Northeast PRC, Mongolia, and portions of Russian Far East & North Korea. Liáo were driven away by Jīn dynasty, forcing them to form Western Liáo state (1124–1218 CE).

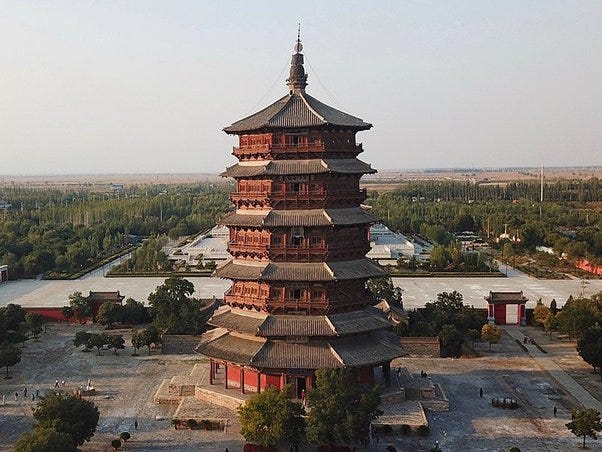

Liáo empire constructed the initial structures of Fogong Tempe Complex (including its wooden pagoda) and Fengguo Temple Complex .

→ Sakyamuni Pagoda of Fogong Temple Complex in Ying County, Shuozhou, Shanxi province, PRC. It is tallest extant wooden pagoda in Zhōngguó (Built 1056 CE) [Source: File:Pagodaoffogongtemple2019.jpg - Wikimedia Commons]

→ Ruined octagonal brick pagoda at Bars-Hot, eastern Mongolia (Built 11th century CE) [Source: File:Bars Hota Mongolia.jpg - Wikimedia Commons]

→ Guanyin Pavilion at Dule Temple Complex in Jizhou District of suburban Tianjin province, PRC. Features roofs with eaves curving near the tips, and dǒugǒngs (wooden brackets) supporting the eaves (Built 10th century CE) [Source: File:独乐寺观音阁正面1.JPG - Wikimedia Commons]

Sòng Empire was founded by Taizu of Sòng following his usurpation of the throne of the Later Zhōu, ending Five Dynasties and Ten Kingdoms period. The Sòng often came into conflict with the contemporaneous Liáo, Western Xià and Jīn dynasties to its north. It was eventually conquered by Mongol-led Yuán dynasty.

Architecture of Sòng dynasty was noted for its towering Buddhist pagodas and boom in temple building. Although literary works on architecture existed beforehand, architectural writing blossomed during Sòng dynasty, maturing into a more professional form that described dimensions and working materials in a concise, organized manner. In addition to the examples still standing, depictions in Song artwork, architectural drawings, and illustrations in published books all aid modern historians in understanding the architecture of the period.

Characteristic features of Sòng architecture include eaves curving slightly upwards at each end.

It was not uncommon for wealthy or powerful families to facilitate the construction of large temple complexes, usually by donating a portion of their family estate to a Buddhist sect. Often the land already contained buildings that could be re-purposed for religions use. Fei family of Jinze town, located just west of Shanghai, converted a mansion on their property into a Buddhist sutra-recitation hall, and later built several other religious buildings around the hall. This spurred a boom in temple construction in the area, causing Jinze to become a major centre of White Lotus sect of Buddhism, which in turn spurred the construction of more temples and lead the town to become a significant location within the Sòng. The nearby town of Nanxiang gained prominence shortly after the fall of the Sòng in large part due to the construction of temples and other religious buildings, which spanned the entire Sòng dynasty.

→ L2R: Yunyan Pagoda (Built 961 CE) , Iron Pagoda (Built 1049 CE) , Lingxiao Pagoda (Built 1045 CE) , Liaodi Pagoda (Built 1055 CE) [Source: Wikipedia pages on respective pagodas]

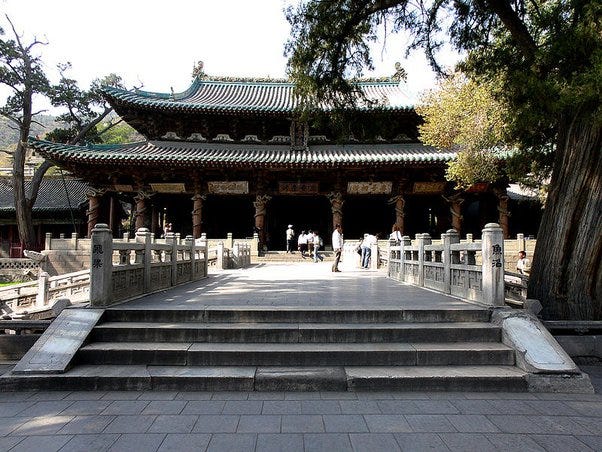

→ Temple of the Saintly Mother, Jinsi, Taiyuan, Shanxi, PRC. It has a double-eaved roof with 9 ridges, and 2 dragon-heads with wide-open jaws biting the ends of the main ridge. The roof is supported by massive dǒugǒng brackets corresponding to drawings in Yíngzào Fǎshì. The eaves of Temple of the Saintly Mother curve upward slightly at each end, a characteristic of Song architecture. The columns of the façade, decorated with dragons that coil around the shafts, become progressively taller with increasing distance to either side of the central pair. The building has a porch around it, the sole example of such a structure; another unique feature of the site is a cross-shaped bridge that leads to Goddess Temple. (Built 1032 CE) [Source: File:Goddess Temple Jinsi.JPG - Wikimedia Commons]

During Sòng Dynasty, the manufacture of glazed tiles was standardized in Yíngzào Fǎshì. During this period, the standard overlap of glazed roof tiles was 40%. With the Sòng-style 40% overlap, it was not possible to have triple tile overlap, as there was a 20% gap between the first plate tile and the third plate tile. Hence, if a crack developed in the second tile, water leakage was inevitable.

Jīn Empire officially known as Dà Jīn (Great Jīn), ruled during 1115–1234 CE emerged from Taizu's rebellion against Liáo dynasty, which held sway over northern Zhōngguó until the nascent Jīn drove the Liáo to Western Regions, where they became known as Western Liáo. After vanquishing Liáo, the Jīn launched a century-long campaign against the Hàn-led Sòng dynasty. Over the course of their rule, the Jurchens of Jīn quickly adapted to Chinese customs, and even fortified the Great Wall against the rising Mongols. Domestically, the Jīn oversaw a number of cultural advancements, such as the revival of Confucianism.

Manjusri Hall of Foguang Temple Complex was constructed in 1137 CE during Jīn dynasty.

→ Manjusri Hall of Foguang Temple Complex (Built 1137 CE) [Source: File:Manjusri Hall.JPG - Wikimedia Commons]

Dà Xià was an empire which existed from 1038 to 1227 CE in what are now the north-western Chinese provinces of Ningxia, Gansu, eastern Qinghai, northern Shaanxi, north-eastern Xinjiang, southwest Inner Mongolia, and southernmost Outer Mongolia.

The government-sponsored state religion was a blend of Böd Tantric Buddhism and Chinese Mahayana Buddhism with a Sino-Nepalese artistic style. The scholar-official class engaged in the study of Confucian classics, Taoist texts, and Buddhist sermons, while the Emperor portrayed himself as a Buddhist King and patron of Lamas. Early in the kingdom's history, Chinese Buddhism was the most widespread form of Buddhism practiced. However, in ~mid-12th century CE Tibetan Buddhism gained prominence as rulers invited Böd monks to hold the distinctive office of state preceptor.

The patronage of Böd Buddhism and consequent incoming of Böd monks led to Böd architecture influence during this period.

→ One Hundred and Eight Stupas — an array of 108 Böd style stūpas on a hillside on the west bank of the Yellow River at Qingtongxia in Ningxia Autonomous Region, PRC [Source: File:108 stupas all 3.jpg - Wikimedia Commons]

→ Hongfo Pagoda in Helan County in Ningxia Autonomous Region, PRC — features a blend of Chinese style and Böd style stūpas with lower 3 storeys being octagonal Chinese style, and upper portion being Böd style [Source: File:Hongfo Pagoda front 2.jpg - Wikimedia Commons]

Dà Yuán/Yeke Yuwan Ulus (Great Yuan State) ruled by Yuán dynasty was a successor state to Yeke Mongγol Ulus after its division and a ruling dynasty of Zhōngguó established by Kublai, leader of the Mongγol Borjigin clan. Yuán dynasty established its rule in Zhōngguó gradually by defeating Southern Sòng dynasty. Its rule was disestablished by Míng dynasty, with Yuán rule continuing in Mongolia as Northern Yuán.

Kublai, the founder of Yuán dynasty, favoured Buddhism, especially Böd variants resulting in Böd Buddhism being established as the de facto state religion.

→ White pagoda of Miaoying temple Complex, Beijing, PRC [Source: wikimedia commons]

→ Ayuwang Pagoda in Dai County in northeast Xinzhou Prefecture in northern Shanxi, PRC [Source: File:代县阿育王塔.jpg - Wikimedia Commons]

14th century CE – 17th century CE

Míng Dynasty (1368 CE – 1644 CE)

Northern Yuán (1368 CE – 1635 CE)

Míng dynasty, officially Dà Míng (Great Míng), was the ruling dynasty of Zhōngguó from 1368 CE to 1644 CE following the collapse of the Mongol-led Yuán dynasty. Although the primary capital of Beijing fell in 1644 CE to a rebellion led by Li Hongji (who established Shùn dynasty, soon replaced by Mǎnzú-led Qīng dynasty), numerous rump regimes ruled by remnants of Míng imperial family, collectively called Southern Míng, survived until 1662 CE.

During Míng Dynasty an innovation occurred through the invention of new wooden components that aided dǒugǒng brackets in supporting the roof. This allowed dǒugǒng to add a decorative element to buildings in the traditional Chinese integration of artistry and function, and bracket sets became smaller and more numerous. Brackets could be hung under eaves, giving the appearance of graceful baskets of flowers while also supporting the roof.

During Míng dynasty, the Silk Road was finally officially abandoned, and Dunhuang slowly became depopulated and largely forgotten by the outside world. Most of Mogao caves were abandoned; the site, however, was still a place of pilgrimage and was used as a place of worship by local people. Yulin caves also fell into disuse during Míng dynasty.

Reconstruction works took place in many temple complexes during Míng dynasty including: Lingyan Temple Complex (in Jinan, Shandong Province, PRC) and Beisi Pagoda of Bao'en Temple Complex (in Suzhou, Jiangsu Province, PRC). White Cloud Temple Complex was also completed under Míng rule.

The City God Temple in Shanghai originated as Jinshan God Temple, dedicated to the spirit of Jinshan, or "Gold Mountain", an island off the coast of Shanghai. It was converted into a City God Temple in 1403 CE, during Zhu Di’s reign (r. 1402–1424 CE) .

→ Ming period Chinese style temple complexes examples:

Dàcí'ēn Temple Complex in Yanta District, Xi'an, Shaanxi, PRC (Present-day structures built mainly 1466 CE and onwards) [Source: Daci'en Temple - Wikipedia]

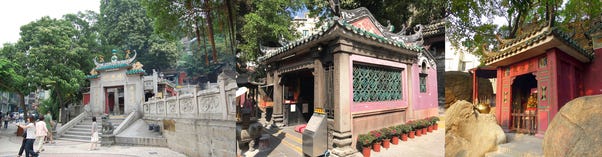

A-Ma Temple Complex in São Lourenço, Macau SAR, PRC — from left to right: entrance, prayer hall and Hall of Benevolence. Dedicated to sea-deity Mazu, he temple is one of the oldest in Macau and thought to be the settlement's namesake. (Built 1488 CE) [Source: A-Ma Temple - Wikipedia]

Bao'en Temple Complex in Sichuan province, PRC — it has 48 types and 2,200 sets of dǒugǒng to support and ornament it. The pagoda inside is called Beisi pagoda. (Built 15th century CE) [Source: Bao'en Temple Pagoda – Things to do in Suzhou - The Ever Wandering]

Northern Yuán existed as a rump state after the collapse of Yuán dynasty in 1368 CE and lasted until its conquest by the Jurchen-led Later Jīn dynasty/Aisin Gurun (precursor of Qīng dynasty) in 1635 CE. Northern Yuán dynasty began with the retreat of the Yuán imperial court led by Toghon Temür (Emperor Huizong of Yuan) to the Mongolian steppe. This period featured factional struggles and the often only nominal role of the Khagan. The last 60 years of this period featured the intensive penetration of Tibetan Buddhism into Mongol society.

→ Northern Yuán Zhōngguó style temples examples:

Erdene Zuu Monastery in near Kharkhorin, Övörkhangai Province, Mongolia — this complex features Zhōngguó, Böd, Mongolian and mixed style structures (Built 1585 CE) [Source: Erdene Zuu Monastery - Wikipedia]

17th century CE – 20th century CE

Qīng dynasty (1616 CE – 1912 CE)

Portuguese Macau (1557 CE – 1999 CE; effective colonial period : 1849 CE – 1974 CE)

Polities:

A lot of present day religious structures in Zhōngguó date to Míng and Qīng dynasties.

Later Jīn dynasty, termed Aisin Gurun (Golden State) in Manju language, was founded by unified Jurchen tribes. In 1636 CE, Hong Taiji officially renamed the realm to "Great Qīng", thus marking the start of the Qīng dynasty. Within decades the Qīng had consolidated its control over the whole of mainland Zhōngguó and Taiwan, and by mid-18th century CE it had expanded its rule into Inner Asia. The dynasty lasted until 1912 CE when it was overthrown in the Xinhai Revolution.

Portuguese Macau (officially Província de Macau (Province of Macau) during 1897-1976 CE and then Autonomous Region of Macau during 1976-1999) was a Portuguese colony from the establishment of the first official Portuguese settlement in 1557 CE to the transfer of its sovereignty to PRC in 1999 CE . It comprised Municipality of Macau and Municipality of Ilhas. Macau was both the first and last European holding in Zhōngguó.

Qīng empire undertook construction of temples following a mix of Böd architecture and Chinese architecture, modelled after some existing monasteries, temple complexes and palaces in Böd: the main and likely the only examples are Eight Outer Temples in Chengde (Heibei province, PRC) constructed in 1713–1780. Temple complexes near-completely following Chinese architecture were also built/rebuilt during this period like Yuantong Temple Complex (in Kunming, Yunnan province, PRC) which achieved its present form under Qīng dynasty.

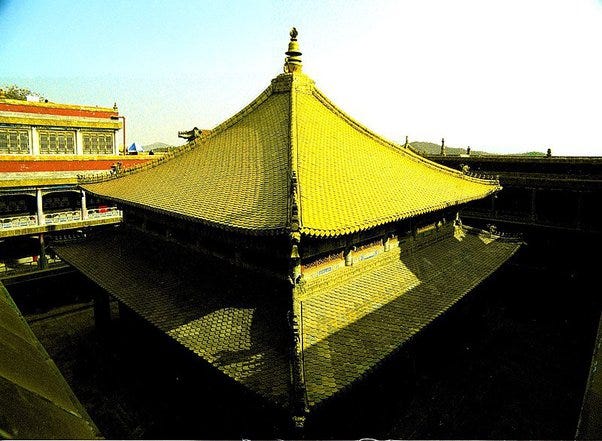

During Qīng dynasty, the overlapping between roof tiles was increased to 70% from Sòng dynasty’s 40%. With the Qīng dynasty style 70% overlapping, the first plate tile was overlapped 70%, 40%, and 10% by the second, third and fourth tiles, respectively — thus even if the second and the third tiles developed cracks, there would be no leakage.

→ Qīng period Böd-Zhōngguó mix architecture temple complexes examples:

Pǔníng temple complex in Chengde, Heibei province, PRC. It is modelled after Samye Monastery, the sacred Buddhist site in Böd [Source: Puning Temple (Hebei) - Wikipedia]

Main temple built in Chinese architecture, with Böd style stūpa on top

Böd style hall with Chinese style eaved roofs

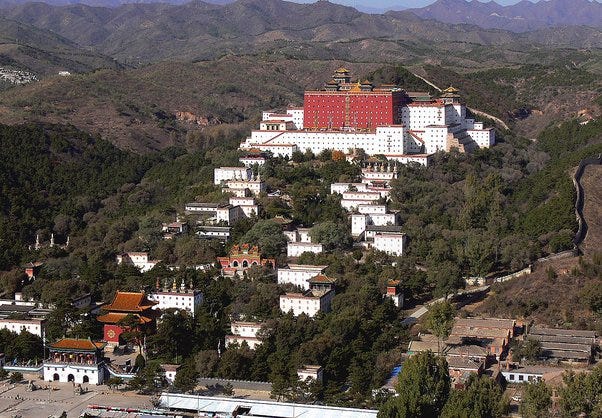

Putuo Zongcheng Temple Complex in Chengde, Heibei province, PRC. It is modelled after Potala Palace in Böd region, present-day Tibet Autonomous Region, PRC [Source: Putuo Zongcheng Temple - Wikipedia]

Aerial view

Five Pagodas Gate with Böd style stūpas

Böd style main hall of the complex

Zhōngguó style Wanfaguiyi Hall

→ Qīng period Zhōngguó style temple complexes examples:

Yuántōng Temple Complex in Kunming, Yunnan province, PRC (present form completed 1686 CE) [Source: File:昆明圆通寺.JPG - Wikimedia Commons]

Dàcí Temple Complex in Chengdu, Sichuan province, PRC (present structure built 17th-19th century CE) [Source: File:Dacisi Temple in chengdu.jpg - Wikimedia Commons]

Mahavira hall of Chongfa Temple Complex , Renmin Park, Tianning District, Changzhou, Jiangsu province, PRC (present-day temple complex built mostly 1875 CE onwards) [Source: File:Chongfa Temple in Changzhou 01 2015-04.JPG - Wikimedia Commons]

The prescribed sacrifices for a Chenghuangshen (City God) are described in the "Auspicious Rites" section of the Da Qing Tongli, the Qīng dynasty manual for rituals. During Qīng dynasty, the emperor appointed a Shing Wong (City God) for all major cities in mainland Zhōngguó to govern and look after their land. Hong Kong had no appointed magistrate and therefore no protection of a Shing Wong. In 1877 CE Hong Kong built their first Shing Wong temple, which was originally named Fook Tak Tsz.

Qīng dynasty also undertook reconstruction of Haibao Pagoda, and its eponymous temple complex in Xingqing District of Yinchuan, Ningxia Autonomous Region, PRC. The pagoda doesn’t seem to follow any of Chinese or Böd pagoda style, but possibly a unique architecture for pagodas in Zhōngguó.

→ Haibao Pagoda in Xingqing District of Yinchuan, Ningxia Autonomous Region, PRC — the pagoda doesn’t seem to follow any of Chinese or Böd pagoda style, but possibly a unique architecture for pagodas in Zhōngguó. [Source: File:海宝塔.jpg - Wikimedia Commons]

Macau's history under Portugal can be broadly divided into three distinct political periods. The first was the establishment of the Portuguese settlement in 1557 CE to 1849 CE. The Portuguese had jurisdiction over the Portuguese community and certain aspects of the territory's administration but no real sovereignty. Next came the colonial period, which scholars generally place from 1849 CE to 1974 CE. As Macau's importance among other territories grew within the Portuguese Empire, Portuguese sovereignty over Macau strengthened and became a constitutional part of Portuguese territory. Chinese sovereignty during this era was mainly nominal. Finally, the third was the transition period or post-colonial period, after the Carnation Revolution in 1974 CE until the handover to PRC in 1999 CE.

→ Portuguese Macau Zhōngguó style temples examples:

Tam Kung Temple Complex in Coloane, Macau, PRC (Built 1862 CE) [Source: File:Tam Kung Miu (Macau) 01.JPG - Wikimedia Commons]

Na Tcha Temple Complex in Santo António, Macau, PRC (Built 1888 CE) [Source: File:Templo Na Tcha, Macao, 2013-08-08, DD 01.jpg - Wikimedia Commons]

Chinese immigrants and Chinese-ethnic communities in Southeast Asia also established Chinese-style temples during this period.

→ Zhōngguó-style temples in Southeast Asia established during 17th-20th century CE examples:

Sam Sing Kung Temple Complex in Sandakan, Sandakan district, Sabah state, Malaysia (Established by various Chinese immigrants 1887 CE) [Source: File:Sandakan Sabah SamSingKungTemple-08.jpg - Wikimedia Commons]

Tam Kung Temple Complex in Sandakan, Sandakan district, Sabah state, Malaysia (Established by Hakka immigrants 1894 CE) [Source: File:Sandakan Sabah Tam-Kong-Temple-01.jpg - Wikimedia Commons]

Zhōnghuá Mínguó (1912 CE – 1949 CE) [Mainland China]

After the 1911 Xinhai Revolution, Qīng dynasty was overthrown and Republic of China came into being. It was overthrown from Chinese Mainland in 1949 CE, leading to the proclamation of present-day People’s Republic of China.

Temples & temple complexes constructed during this period mainly follow regular Zhōngguó architecture with little to no modifications besides possible introduction of industrial materials.

→ Republic period Chinese style temple complexes examples:

Jílè Temple Complex in Harbin, Heilongjiang province, PRC (Built 1921–1924 CE) [Source: File:ハルビン極楽寺玄関.jpg - Wikimedia Commons]

Sānzǔ Temple Complex on Mount Tianzhu, Qianshan, Anhui province PRC (Built 1944 CE) [Source: A snapshot of Sanzu Temple]

Zhōnghuá Rénmín Gònghéguó (1949 CE – present)

Industrial grade materials and better logistics are the primary changes seen in Zhōngguó style temples of modern period. Traditional Chinese style and layout is the preferred format of temple complexes, and Böd style influence is nearly absent, especially in Central Plains.

Traditional Chinese layout and forms seem to be maintained outside PRC as well, especially in case of temples established by Chinese-ethnic or Sinicized communities.

→ Zhōngguó style temple complexes in PRC examples:

Jing'an Temple Complex in Jing'an District, Shanghai, PRC — most of the buildings are constructed in traditional Chinese architecture, with the pagoda on top left incorporating the Indian Mahabodhi Temple based structure over it. (Built 1983 CE onwards) [Source: File:静安寺·上海静安.jpg - Wikimedia Commons

Tianning Temple Complex in Changzhou, Jiangsu Province, PRC — features the currently tallest pagoda in the world at 154m. The pagoda is an octagonal structure with flat eaves while the hall nearby features sharply curving eaves. (Built 2002–2007 CE) [Source: Tianning Temple (Changzhou) - Wikipedia]

→ Zhōngguó style temples in Southeast Asia established 20th century CE onwards examples:

Peak Nam Toong Temple Complex in Kota Kinabalu, Kota Kinabalu District, Sabah state, Malaysia (Established 1970 CE) [Source: File:KotaKinabalu Sabah Peak-Nam-Tong-Temple-01.jpg - Wikimedia Commons]

Thean Hou Temple Complex in Seputeh, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia (Established by Hainam nang in 1981 CE) [Source: File:Thean Hou Temple, Kuala Lumpur-1.jpg - Wikimedia Commons]

→ Zhōngguó style temples in Africa examples:

Nan Hua Fo Guang Shan Temple Complex in Cultural Park suburb of Bronkhorstspruit, South Africa (Built 1992–2005 CE) [Source: Category:Nan Hua Temple - Wikimedia Commons]

Shaolin Temple Complex in Lusaka, Zambia (Built 2019–2021 CE) [Source: (Hello Africa) First Shaolin Temple opens in Zambia]

→ Zhōngguó style temples in Americas examples:

Thien Hau Temple Complex in Chinatown of Los Angeles, California, USA — it primarily serves the Sino-Viet community formed by Viet refugees in the area, with the enshrined images imported from Vietnam in 1990. (Built 1980–2005 CE) [Source: File:Los Angeles, Buddhist Temple Thien Hau, 2016.03.27 (03) (28755210693).jpg - Wikimedia Commons]

Structural Details

Votive Columns

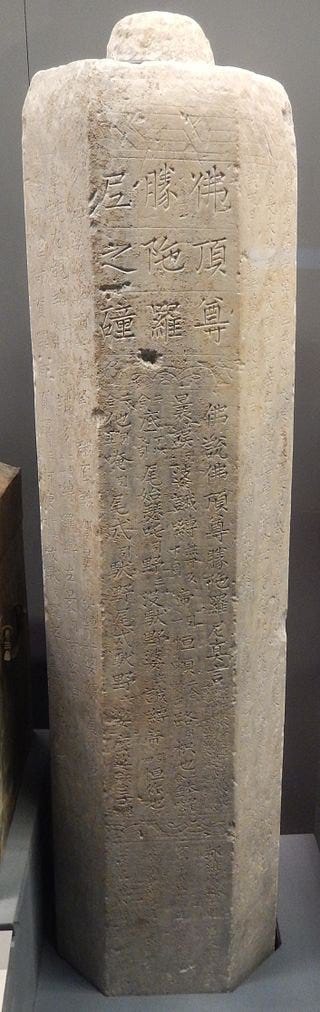

Tuóluóní chuáng a.k.a. Jīngchuáng

It is a type of stone pillar engraved with dhāraṇī-sūtras or simple dhāraṇī incantations. These pillars were usually erected outside Buddhist temples, and became popular during Táng dynasty.

→ Míng dynasty hymn pillar [Source: File:Ming Dharani pillar from Biyun Temple.jpg - Wikimedia Commons]

Decorative elements

Lóng and Fènghuáng

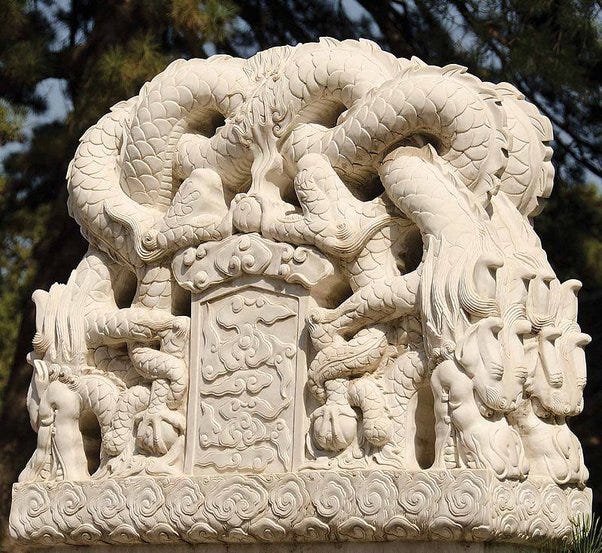

Lóng can be found as decorative sculptures over roofs and pillars, and in outdoors of temple complexes in form of decorative statues.

→ Marble statue of double Lóng at Jietai Temple Complex [Source: File:Jietai Temple Double Dragon Statue.jpg - Wikimedia Commons]

→ Lóng columns at Temple of Confucius, Qufu [Source: File:曲阜孔庙大成殿盘龙柱群.jpg - Wikimedia Commons]

→ Lóng figure on the roof of a temple [Source: File:Temple rooftop dragon in Taiwan (1).jpg - Wikimedia Commons]

Fènghuáng may also be used over over roofs of structures in a temple complex.

→ Fènghuáng on the roof of Longshan Temple in Taipei, RoC [Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=14932961]

A zhàobì (照壁 ; screen wall), or yǐngbì (影壁 ; shadow wall) , is a screen that is placed at the front of the temple to stop ghosts or evil spirits from entering. The idea is that evil spirits cannot turn corners (hence the zig-zag bridges of Zhōngguó gardens), and so the wall screens the main entrance. A temple may have a dragon wall. This is an aesthetic feature and projects the high-status of the temple to visitors. Usually reserved for imperial palaces, a Jiǔ Lóng Bì (九龍壁 ; nine dragon wall) indicates the imperial sponsorship of a temple.

→ Nine Dragon Wall, Fayu Temple, Putuoshan [Source: Chinese Buddhist Temples 101]

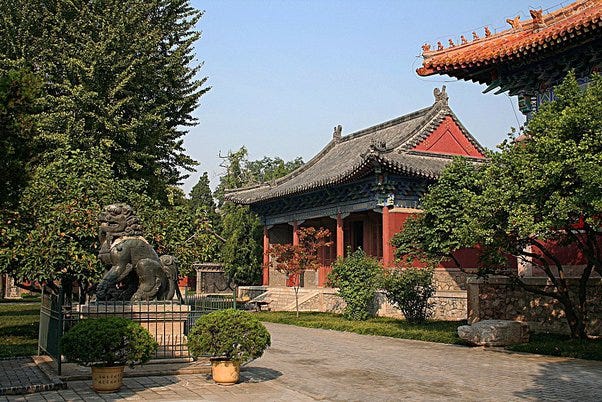

Shī (Guardian Lions)

The concept, which originated and became popular in Zhōngguó Buddhism, features a pair of highly stylized lions, often one male with a ball and one female with a cub, which were thought to protect the building from harmful spiritual influences and harmful people that might be a threat. Used in imperial Zhōngguó palaces and tombs, the lions subsequently spread to other parts of Asia including Tibet, Taiwan, Nihon, Joseon, Thailand, Myanmar, Vietnam, Sri Lanka, Nepal, Cambodia, Laos and Malaysia.

The lions are traditionally carved from decorative stone, such as marble and granite or cast in bronze or iron. Due to high cost of these materials and the labour required to produce them, private use of Shī was traditionally reserved for wealthy or elite families. A traditional symbol of a family's wealth or social status was the placement of guardian lions in front of the family home.

Shī can be classified as follows:

Material

Shíshī (石獅 ; Stone lion)

Tóngshī (銅獅 ; bronze lion)

Ruìshī (瑞獅 ; auspicious lion)

→ Guardian lions examples:

Guardian lions outside the Chinese Museum in Melbourne. In accordance with feng shui, the male lion, with the ball under his right paw, is on the right, and the female, with the cub under her left paw, is on the left. [Source: File:The entrance of the Chinese Museum, Melbourne.jpg - Wikimedia Commons]

A guardian lion of Wen Wu Temple Complex in Taiwan, RoC [Source: File:Wen Wu Temple - Chinese lion.jpg - Wikimedia Commons]

Foundations

The most typical building, at least for larger structures for the elite or public use such as temples, halls, and gate towers, was built on a raised platform made of compacted earth and faced with brick or stone.

The earliest examples date to Shāng dynasty (~1600 BCE – 1046 BCE) and as time goes on they become larger with more levels added to create stepped terrace. Examples of earth foundations at Erlitou sites, which date to between ~1900–1550 BCE, range in size from 300m2-9,600m2 and often include underground ceramic sewage pipes.

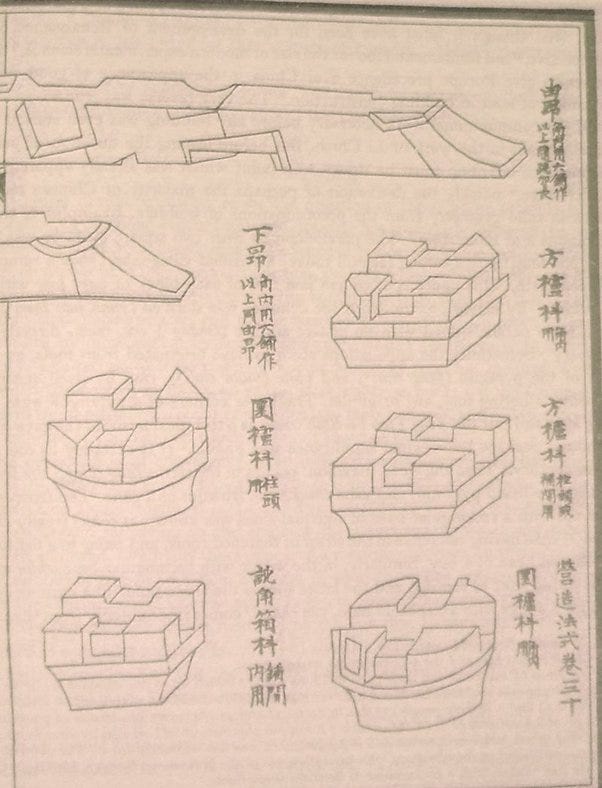

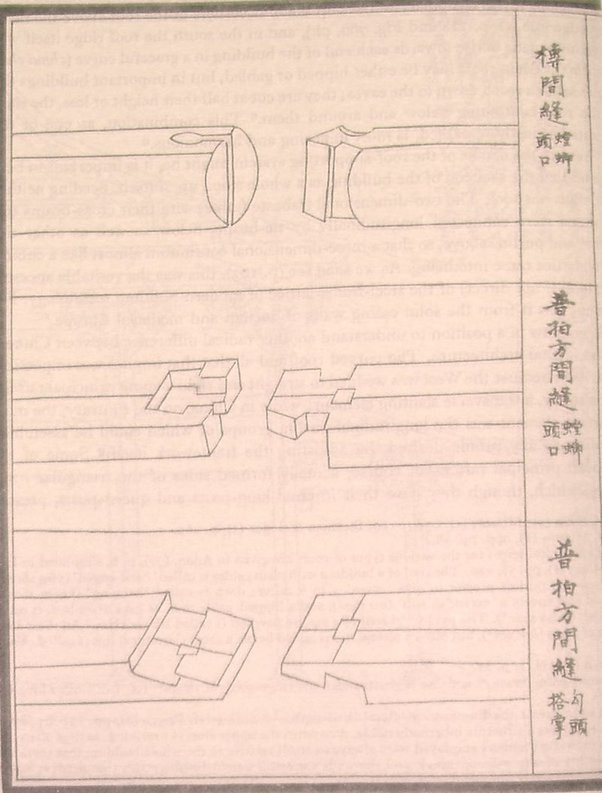

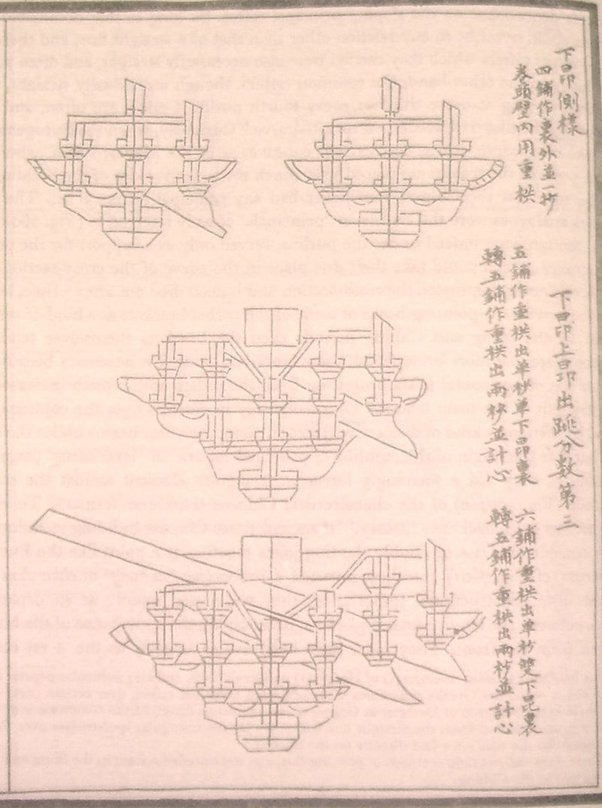

Joints and brackets

Among the popular manuals of describing Zhōngguó architecture techniques is Yíngzào Fǎshì. It was authored by Lǐ Jiè (1065–1110 CE) , Directorate of Buildings and Construction during the mid Sòng Dynasty.

→ Diagrams of bracket & joints in Yíngzào Fǎshì:

Diagram of bracket and cantilever arms from Yíngzào Fǎshì [Source: File:Yingzao Fashi 5 desmear.JPG]

Sliding dovetail, lap dovetail and stepped bevel splice joints of tie beams and cross beams from Yíngzào Fǎshì [Source: File:Yingzao Fashi 2 desmear.JPG]

Bracket arm clusters containing cantilevers [Source: File:Yingzao Fashi 3 desmear.JPG]

Dǒugǒng (斗拱 ; cap [and] block)

Dǒugǒng is part of the network of wooden supports essential to the timber frame structure of traditional Zhōngguó building. Because the walls in these structures are not load-bearing (curtain walls), they are sometimes made of latticework, mud or other delicate material. Walls functioned to delineate spaces in the structure rather than to support weight.

Multiple interlocking bracket sets are formed by placing a large wooden block (dǒu) on a column to provide a solid base for the bow-shaped brackets (gǒng) that support the beam or another bracket above it. The function of dǒugǒng is to provide increased support for the weight of the horizontal beams that span the vertical columns or pillars by transferring the weight on horizontal beams over a larger area to the vertical columns. This process can be repeated many times, and rise many stories. Adding multiple sets of interlocking brackets reduces the amount of strain on the horizontal beams when transferring their weight to a column. Multiple interlocking brackets also allows structures to be elastic and to withstand damage from earthquakes.

The use of dǒugǒng first appeared in buildings of the late centuries BCE and evolved into a structural network that joined pillars and columns to the frame of the roof.

It was widely used in ancient Zhōngguó temples during Spring and Autumn period (770 BCE – 476 BCE) and developed into a complex set of interlocking parts during Táng and Sòng periods. The pieces are fitted together by joinery alone without glue or fasteners, due to the precision and quality of the carpentry.

After Sòng Dynasty, brackets and bracket sets became more ornamental than structural when used in palatial structures and important religious buildings.During Míng Dynasty the invention of new wooden components that aided dǒugǒng in supporting the roof allowed dǒugǒng to add a decorative element to buildings in the traditional Zhōngguó integration of artistry and function, and bracket sets became smaller and more numerous. Brackets could be hung under eaves, giving the appearance of graceful baskets of flowers while also supporting the roof.

→ Dǒugǒng inside the East Hall of Foguang Temple Complex in Wutai County, Shanxi Province, PRC (built 857 CE during Táng Dynasty) [Source: File:Foguang Temple 5.JPG]

Halls and Pavilions

Tiānwángdiàn (simplified Chinese: 天王殿 ; Hall of Four Heavenly Kings)

Tiānwángdiàn is the first important hall after or combined with Shānmén (mount gate) in Pure Land Buddhist temples and Chan Buddhist temples and is named due to Four Heavenly Kings statues enshrined in the hall.

→ Four Heavenly Kings Hall at Guangfu Temple Complex, in Shanghai, PRC [Source: File:Guangfujiangsi.JPG - Wikimedia Commons]

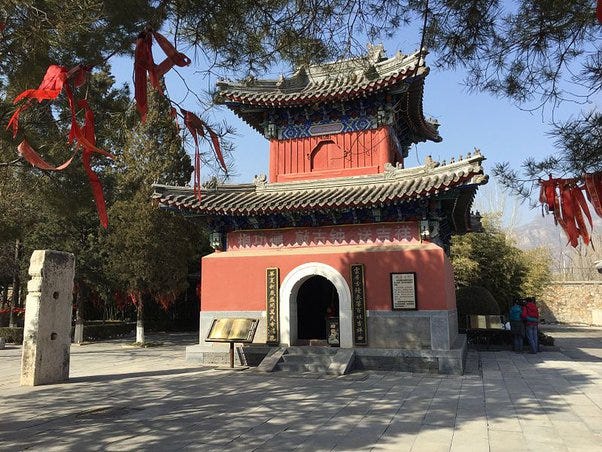

Zhōnglóu (simplified Chinese: 钟楼 ; Bell tower)

Zhōnglóu is usually located on left side of Tiānwángdiàn. It is generally a 3-storey pavilion with a large bell hung in it. The loud and melodious sound of the bell is often used to convene monks. In each morning and night, beating the bell 108 times symbolizes the relief of the 108 kinds of trouble in the human world.

→ Zhōnglóu at Yunju Temple Complex, in Beijing [Source: File:Bell Tower of Yunju Temple (20150223134805).JPG - Wikimedia Commons]

Dharma Hall a.k.a. Lecture Hall

Dharma Hall is the place for senior monks to preach and generally ranks right after Mahāvīra Hall in a Hàn Buddhist temple complex.

With the similar architecture form with other halls, Dharma Hall is more spacious. In the central back, there is a high platform with a sitting chair putting in the middle. In front of the chair is a table with a small sitting Buddha on it, behind the platform is a screen or a picture of lion which is also known as "Roaring lion" in Buddhism hung on the wall. Seats are placed on both sides of the platform with bells and drums for senior monks to beat when they are preaching. There are also seats on both sides of the monks' seats for laymen to listen to the Buddha Dharma by senior monks.

→ Dharma Hall at Hanshan Temple, in Suzhou, Jiangsu, PRC [Source: File:KAM 7332 (6469404627).jpg - Wikimedia Commons]

Qiélándiàn (simplified Chinese: 伽蓝殿 ; Sangharama Palace Hall)

It is the east annex hall of Mahāvīra Hall. "Sangharama" with the short form "garan" (僧伽藍摩), means "gardens of monks" (眾園). In Buddhism, it originally refers to constructing the base of monks' dormitories (僧舍) and later it refers to the general term of temples, including land and buildings. In Hàn Buddhist temple complexes, this hall houses Eastern Hàn military general Guān Yǔ .

→ Hall of Sangharama Palace at Hongfa Temple Complex, in Shenzhen, Guangdong, PRC [Source: File:Hongfa Temple, Shenzhen 028.jpg - Wikimedia Commons]

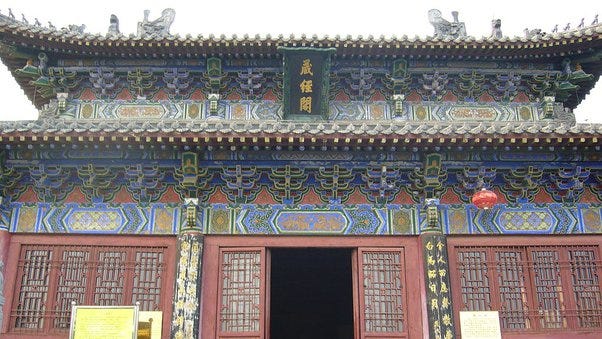

Cángjīnggé (simplified Chinese: 藏经阁; traditional Chinese: 蔵經閣 ; Buddhist Texts Library)

Cángjīnggé is a building that houses Hàn Buddhist Canon (Dàzàngjīng; 大藏經). Cángjīnggé are generally 2-storey buildings built at the highest point of the temple. The upper storey is for storing sutras and the lower layer is the "Thousand Buddha Pavilion" (千佛閣).

→ Cángjīnggé at White Horse Temple Complex in Luoyang, Henan province, PRC [Source: File:Temple roofline.jpg - Wikimedia Commons]

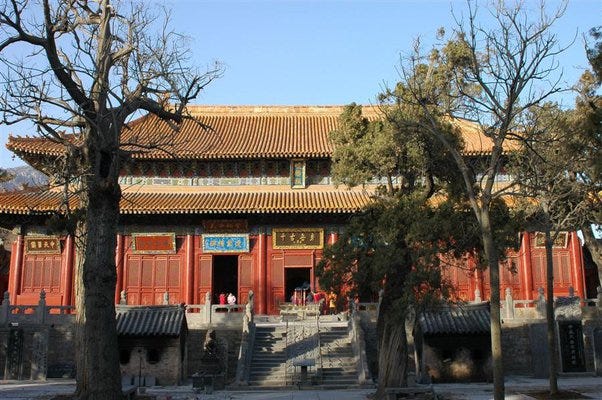

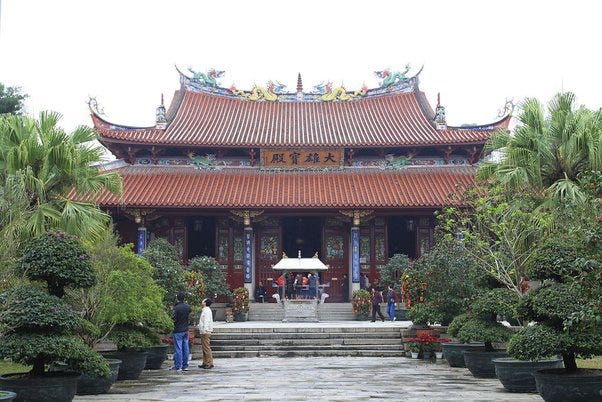

Dàxióng Bǎodiàn (Simplified Chinese: 大雄宝殿 , Traditional Chinese: 大雄寶殿 ; Mahāvīra Hall / Great Hero Hall / Main Hall)

Great Hero Hall, usually simply known as a Main Hall, is the main hall or building in a traditional Zhōngguó Buddhist temple complex, enshrining representations of Gautama Buddha and various other Buddhas and Bōdhīsattvas. The term "Mahāvīra Hall" or "Hall of the Mahāvīra", is a reverse translation, employing the original Saṁskr̥ta term in place of its Chinese or English equivalent.

It is generally located in the north of the Heavenly King Hall and serves as the core architecture of the whole temple and also a place for monks to practice.

→ Main Hall of Shanhua Temple Complex in Datong, Shanxi Province, PRC [Source: File:Shanhua Temple 1.jpg - Wikimedia Commons]

Pagodas

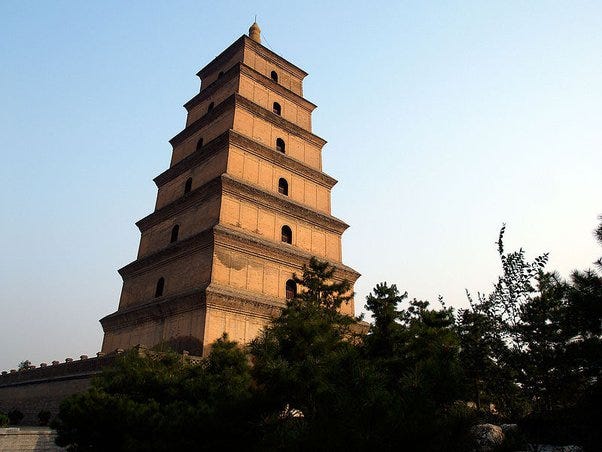

Zhōngguó pagodas in general have little to no taper with height, and have 4, 6 or 8 sides. The tower, even though giving the perception of of many stories, is usually hollow. The eaves are generally found as 2 types of extremes — either no curve at the tips, or extreme curve at the tips.

Square Type Pagodas

→ Square type with visible taper and flat eaves with little protrusion :

Dayanta (Big Wild Goose Pagoda) in Xi'an, Yanta District, Shaanxi, PRC (built 704 CE) [Source: File:Giant Wild Goose Pagoda.jpg]

→ Square type with little taper, highly protruding eaves with curving tips:

Xingshengjiao Temple Pagoda in Songjiang town, suburban Shanghai, PRC — [Source: File:Pagoda at Xingshengjiao Temple.jpg]

→ Square Pavilion type pagoda :

Four Gates Pagoda in Shandong province, PRC (built 611 CE Suí dynasty style) [Source: File:Four gates pagoda shandong 2006 09.jpg]

Dragon-and-Tiger Pagoda in central Shandong Province, PRC (built under Táng dynasty) [Source: File:Dragon and tiger pagoda shandong 2006 09 2.jpg - Wikimedia Commons]

Hexagonal Type Pagodas

→ Hexagonal type pagoda with little taper, highly protruding eaves with curving tips :

Liuhe Pagoda in southern Hangzhou, Zhejiang province, PRC — it gives the impression of having 13 stories, but has only 7 actual stories. (built 12th century CE after being destroyed and rebuilt multiple times before that) [Source: File:Hangzhou Liuhe Ta 20120518-05.jpg]

Octagonal Type Pagodas

→ Octagonal type pagoda with little taper, flat eaves :

Lingxiao Pagoda in Zhengding, Hebei Province, PRC — it has 9 eaves and equal number of stories (built 11th century CE) [Source: File:Lingxiaopagodazhengding.jpg - Wikimedia Commons]

→ Octagonal type with visible taper :

Liaodi Pagoda of of Kaiyuan Monastery, Dingzhou, Hebei Province, PRC. This pagoda functions both as a religious site and a watchtower. (built 11th century CE Sòng dynasty period) [Source: File:Dingzhou Liaodi Pagoda 3.jpg]

→ Octagonal Pavilion type pagoda : Nine Pinnacle Pagoda a.k.a. Jiuding Pagoda in near Qinjiazhuang Village, Liubu Town, in Licheng District, Shandong province, PRC (built 8th century CE) [Source: File:Jiudingta 2008 07 15 1.jpg]

Roofs

Roofing Material

Glazed Roof tiles:

Glazed tiles have been used in Zhōngguó since Zhōu Dynasty as a material for roofs.

During Sòng Dynasty, the manufacture of glazed tiles was standardized in Lǐ Jiè's Architecture Standard.

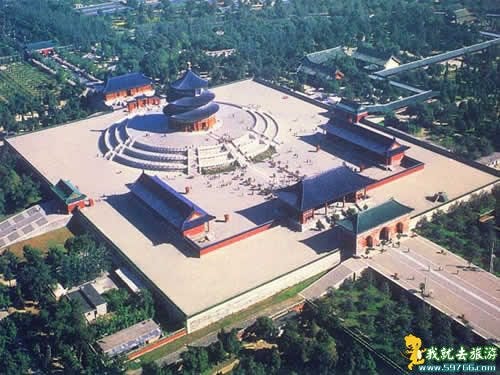

In Míng Dynasty and Qīng Dynasty, glazed tiles became ever more popular for top-tier buildings, including palace halls in Forbidden City, and ceremonial temples (eg. Heavenly Temple of central Beijing).

There are two main types of Zhōngguó glazed tiles: glazed tubular tile and glazed plate tile.

Glazed tubular tiles are moulded into tube shape on a wooden mould, then cut into halves along their length, producing two tubular tiles, each semi-circular in section. A tube-shaped clay mould can be cut into four equal parts, with a cross section of a quarter of a circle, then glazed into a four plate tile.

Glazed tubular tiles used at the eave edge have an outer end made into a round shape top, often moulded with the pattern of dragon.

Glazed plate tiles are laid side by side across and overlapping each other. In Sòng Dynasty, the standard overlap was 40%, which increased to 70% in Qīng dynasty. With Sòng-style 40% overlap, it was not possible to have triple tile overlap, as there was a 20% gap between the first plate tile and the third plate tile. Hence, if a crack developed in the second tile, water leakage was inevitable. On the other hand, with Qīng dynasty style 70% overlapping, the first plate tile was overlapped 70%, 40%, and 10% by the second, third and fourth tiles, respectively; thus even if the second and the third tiles developed cracks, there would be no leakage.

Eave-edge plate tiles have their outer edges decorated with triangles, to facilitate rain-shedding.

Roof decoration figures

Figures of Zhōngguó mythological figures like Lóng, Fènghuáng and Chīwěn are commonly used over over roofs of structures in a temple complex.

→ Lóng figure on the roof of a temple in RoC [Source: File:Temple rooftop dragon in Taiwan (1).jpg - Wikimedia Commons]

→ Fènghuáng on the roof of Longshan Temple in Taipei, RoC [Source: File:Longshan Temple - Fenghuang.jpg - Wikimedia Commons]

→ Chīwěn on the roof of Longyin Temple, Chukou, RoC [Source: File:Temple of Chukou 04- Dragons.jpg - Wikimedia Commons]

Roof types

The wooden posts supported a thatch roof in earlier architecture and then a gabled and tiled roof with the corners gently curving outwards and upwards at the corners. By 3rd century CE hip and gable roofs are common.

A roof type commonly seen in Zhōngguó style temples in general is the flat-eaved and extreme curve tip eave; in case of curved eaves, the points are always curved upwards.

Another common roof style is Swallowtail roof (Traditional Chinese: 燕尾脊; swallowtail ridge), part of the architectural style of Hoklo people. The term refers to a roof that has an upward-curving ridge shaped like the tail of a swallow. The degree of curving may vary. The "swallowtail" in question can be single- or double-layered and is typically decorated with a large amount of colourful carvings.

Roofs with upwards pointed eaves

→ Single roof with upwards pointed eaves :

Dai Miao at the foot of Mount Tai, Tai'an, Shandong province, PRC [Source: File:Mount tai dai temple 2006 09.jpg]

→ Multi-Roof with upward pointed eaves :

Guangxiao Temple in Yuexiu District, Guangzhou, Guangdong province, PRC [Source: File:Guangxisi Gulou.jpg]

Maitreya Hall at Chi Lin Nunnery in Hong Kong, PRC [Source: File:Chi Lin Nunnery (2037672635).jpg]

Flat roofs

→ Completely flat roof :

Dailuoding Temple in Wutai County, Shanxi, PRC [Source: File:Dailuoding Temple5.JPG]

→ Almost flat roof, with eaves slightly curving upwards at tips :

Zhongyue Temple on Mount Song, Dengfeng district of Henan Province, PRC [Source: File:Zhongyuemiao.JPG - Wikimedia Commons]

Swallowtail roofs

→ Simple swallowtail roof :

A Taoist shrine for the deity Tudigong in Kaohsiung, Taiwan, RoC [Source: File:鎮福社.JPG - Wikimedia Commons]

→ Highly decorated swallowtail roof :

Main Hall of Nánshān Temple, Changchow, Fujian province, PRC [Source: File:Zhangzhou Nanshan Si 20120225-4.jpg]

→ Highly curved and richly decorated swallowtail multi-roof :

Mazu Temple in Chiayi City, Taiwan, RoC [Source: File:Singang Fengtian Temple 20081012.jpg]

Mén (Gateways)

Gates by Structure Type

Què (simplified Chinese: 阙 - Ceremonial Gate tower)

Què is a freestanding, ceremonial gate tower in traditional Zhōngguó architecture.

First developed in Zhōu Dynasty (1046 BCE – 256 BCE), què towers were used to form ceremonial gateways to tombs, palaces and temples throughout pre-modern Zhōngguó till Qīng Dynasty (1644 CE – 1912 CE).

The use of què on spirit ways declined after Eastern Hàn period (25 CE – 220 CE). Some què from 3rd and 4th century CE have been found in Sichuan, but, as British historian Ann Elizabeth Paludan notes, only in the province's more remote and presumably culturally conservative parts.

Generally, after Eastern Hàn era, the role of que on the spirit way was assumed by huabiao pillars (found in palaces and tombs).

→ Eastern Hàn stone-carved que pillar gates of Dingfang, Zhong County, Chongqing, PRC that once belonged to a temple dedicated to the Warring States era general Ba Manzi [Source: File:忠縣丁房雙闕02.jpg - Wikimedia Commons]

Wūtóumén (烏頭門 ; black top gate) a.k.a. Páifāng ak.a. Páilóu

Páifāng is a traditional style of Zhōngguó architectural arch or gateway structure.

During the Táng dynasty, it was called a wūtóumén (烏頭門 ; black top gate), as the top of the two posts were painted black. A wūtóumén was reserved for officials of rank 6 or higher.

The construction of wūtóumén was standardized in Yíngzào Fǎshì of the mid Sòng dynasty. It consisted of two posts and a horizontal beam forming a frame and two doors.

By Míng and Qīng dynasties, it was called a Páilóu or Páifāng, and evolved into a more elaborate structure with more posts and gates, with a superstructural gable on top; the highest rank was a 5-gate 6-post 11-gable páilóu .

Páifāngs come in a number of forms:

Wooden pillars placed onto stone bases, which are bound together with wooden beams. This type of Páifāng is always beautifully decorated, with the pillars usually painted in red, the beams decorated with intricate designs and Zhōngguó calligraphy, and the roof covered with coloured tiles, complete with mythical beasts—just like a Zhōngguó palace.

True archways made of stone or bricks. The walls may be painted, or decorated with coloured tiles; the top of the archways are decorated like their wooden counterparts.

Plain white stone pillars and beams, with neither roof tiles nor any coloured decoration, but feature elaborate carvings created by master masons. Built mainly on religious and burial grounds.

Hàn dynasty style: consists of two matching towers, such as in Beihai.

→ Singular gateway with architraves : Entrance to Yonghe Temple Complex, Beijing, PRC [Source: File:Yonghe Gong Lama Temple.jpg]

→ Triple gateway with architraves : Baiyun Temple Complex , a Taoist temple complex in Beijing, PRC [Source: File:WhiteCloudpic1.jpg - Wikimedia Commons]

→ Triple gateway with true arches : Gateway of Puotuo Zongcheng temple complex, Chengde, Heibei province, PRC [Source: File:Color glaze gateway Puotuo Zongcheng.jpg]

→ Pentuple Gateway with architraves : Thian Hock Keng Temple Complex at Telok Ayer Street, Singapore — shows swallotail ridge roof with dragon decorations [Source: File:Thian Hock Keng Temple - entrance.jpg]

Star gates

Some temple complexes have gates called star gates. These are usually architraved gateways that may exist independently or in groups, but are not necessarily connected to each other.

→ Various star gates in Temple of Earth complex [Source: Temple of Earth-Wikipedia]

2 Star gates (in foreground and background) at the stairway to the altar

Star gate leading into a hall in the complex

Star Gates marking the boundary of the altar

Gateways by role / position

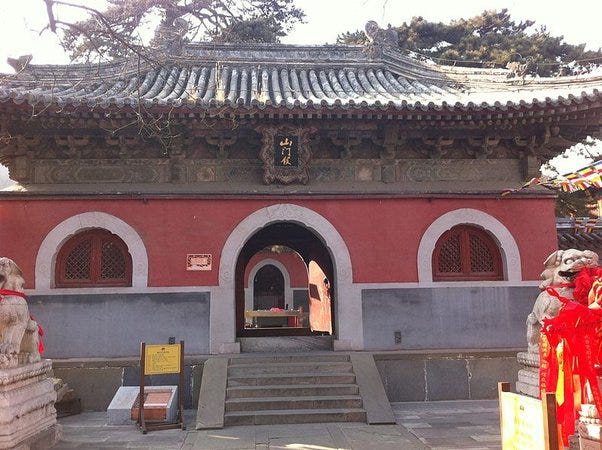

Shānmén (simplified Chinese: 山门; traditional Chinese: 山門 ; Gate of Three Liberations)

Shānmén, is the most important gate of a Chan Buddhist temple complex.

Historic Shānméns in Zhōngguó region are either a gateway of Páifāng style, or a more substantial building, typically with three archways. Where a substantial building is used, the two side gateways might be simplified to arched or circular windows, leaving only the middle gate for access.— the gate building may be called "Hall of Three Liberations" or "Hall of the Mountain Gate" (山門殿) .

Traditionally, if the Shānmén takes the form of a gate building, statues of two guardians of Buddhist law are erected in that hall as guardians of the entrance (identified as "Heng and Ha"). This is the arrangement at Jietai Temple Complex in Beijing, PRC.

Some Chan Buddhist temples may feature the following variations of Shānméns:

Shānmén combined with Four Heavenly Kings Hall so that the Four Heavenly Kings serve as guardians of the gateway to the monastery

Shānmén combined with Maitreya Hall, with a statue of the Maitreya Buddha erected in the centre of the hall

Shānmén combined with both Maitreya Hall and Four Heavenly Kings Hall

→ Examples of Shānmén:

Páifāng type Shānmén at Lushan Temple Complex, in Yuelu District of Changsha city, Hunan province, PRC [Source: File:Changsha Yuelu Shan Lushan Si 2014.03.04 11-09-11.jpg - Wikimedia Commons]

Hall of Mount Gate at Jietai Temple Complex, in Beijing, PRC. The arched windows represent the traditional side gateways. [Source: File:Entrance to Jietai Temple (20150117133227).JPG - Wikimedia Commons]

Temple Complexes

Zhōngguó temple complexes are usually oriented in a north-south axis with entrance towards the south. The arrangement and functions of various halls have been discussed above.

→ Temple complexes examples:

Zunsheng Temple Complex in Wutai County, Shanxi, PRC [Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=4235697]

Aerial view of Temple of Heaven complex, Beijing, PRC [Source: China-iammodernman blog]

→ Temple complexes layouts examples:

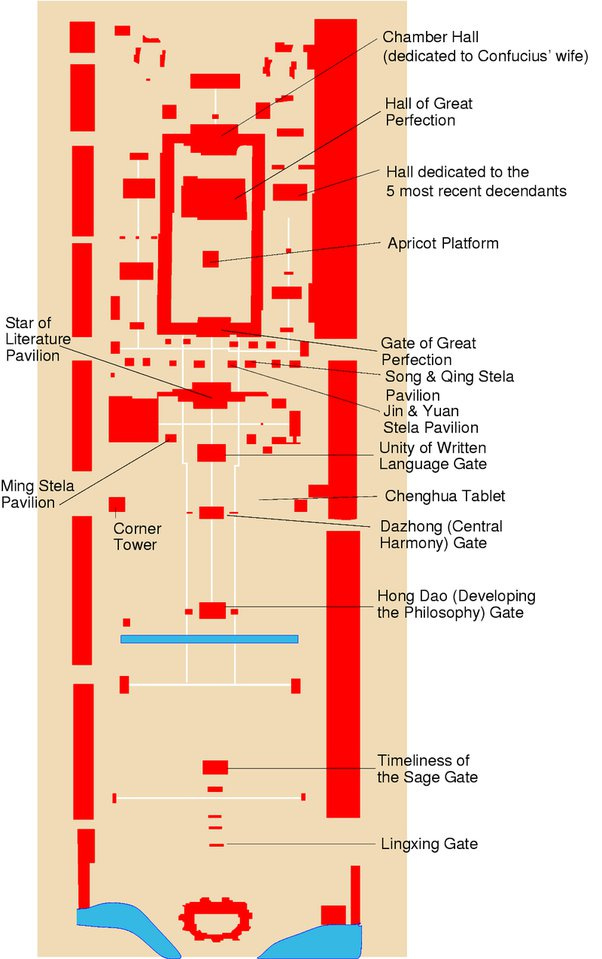

Layout of Kǒng miào complex in Qufu, Shandong Province, PRC [Source: http://a.org/wiki/Temple_of_Confucius,_Qufu#/media/File:Confuciustemplequfu.png]

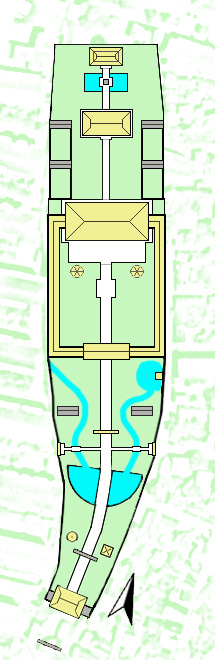

Layout of Fuxue Wénmiào in Jinan, Lixia District, Jinan Prefecture, Shandong Province, PRC [Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:%E6%B5%8E%E5%8D%97%E6%96%87%E5%BA%99_map.jpg]

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Chinese_architecture

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Martial_temple

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Wen_Wu_temple

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Han_dynasty

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Western_Regions