Temple Architecture Styles : Nihon architecture

Nihon temple architecture (Japanese temple architecture)1 can be broadly classified on basis of the temple being a Buddhist Temple or Shintō Temple, but there is some overlap between them as well. A significant influence on Nihon temples has been Zhōngguó Free-standing Temple Architecture. The architecture developed mainly on Hokkaido, Honshu, Kyushu and Shikoku.

General Terms:

Buddhist Temple:

tera (寺) (kun reading)

ji (寺) (on reading)

in (院) — used mainly for minor temples

Shintō Temple: a Shintō temple’s name consists of 2 parts - meishō (名称; proper name {location}) and shōgō (称号; title). The titles are as below

Generic terms

Jinja (神社) {generic term}

Yashiro (社) {generic term}

Mori (杜; grove)

Minor Shrines

suffix -sha or -ja (社) {minor shrine}

Hokora/hokura (神庫) {minor shrine usually on roadside}

Shrines with high status/enshrining imperial household member/sometimes tradition

Jingū (神宮) {shrine of particularly high status}

Miya (宮) {shrine enshrining a special deity or a member of the Imperial household like the empress; sometimes only used as traditional name}

-gū (宮) {shrine enshrining an imperial prince; sometimes only used as traditional name}

taisha or ōyashiro (大社; great shrine)

Development

Early development

Yayoi-period (Neolithic and Bronze Age) village councils sought the advice of ancestors and other kami (nearly equivalent to deities), and developed instruments, yorishiro, to evoke them. Yoshishiro means "approach substitute" and were conceived to attract the deities to allow them physical space, thus making them accessible to humans.

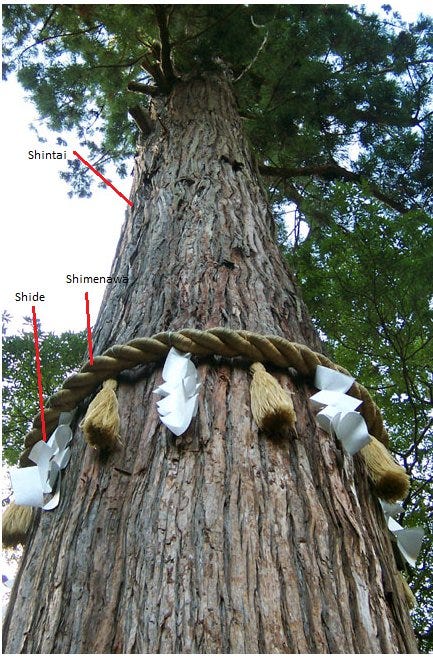

Village-council sessions were held in quiet spots in the mountains or in forests near great trees or other natural objects that served as yorishiro. These sacred places and their yorishiro gradually evolved into today's Shintō shrines, whose origins can be still seen in the Nihon words for "mountain" and "forest", which can also mean "shrine". Many shrines have on their grounds one of the original great yorishiro: a big tree, surrounded by a sacred rope called shimenawa.

The first buildings at places dedicated to worship were hut-like structures built to house some yorishiro. A trace of this origin can be found in the term hokura (神庫 ; “deity storehouse”), which evolved into hokora (written with the same characters 神庫), and is considered to be one of the first words for shrine.

True shrines arose with the beginning of agriculture, when the need arose to attract kami to ensure good harvests. Hints of the first shrines can still be found here and there. Ōmiwa Shrine in Nara contains no sacred images or objects because it is believed to serve the mountain on which it stands; images or objects are therefore unnecessary. For the same reason, it has a worship hall, a haiden (拝殿), but no place to house the kami, called shinden (神殿).

6th century CE – 8th century CE

Polity:

From Asuka period in 6th century, as a sub-division of Yamato period (conventionally starting from 250 CE till 710 CE), is the first time in Japanese history when the Tennō (Emperor of Japan) ruled relatively uncontested from modern-day Nara Prefecture, then known as Yamato Province, hence the name of the broader period.

Yamato name became synonymous with all of Nippon as the Yamato rulers suppressed other clans and acquired agricultural lands. Based on Zhōngguó’s models (including the adoption of Zhōngguó written language), they developed a central administration and an imperial court attended by subordinate clan chieftains but with no permanent capital. By mid-7th century CE, the agricultural lands had grown to a substantial public domain, subject to central policy.

Asuka period is distinguished by the change in the name of the country from Wa (倭), the oldest attested name of Japan, to Nippon (日本) in 701 CE.

Nara period begins from 710 CE with Empress Genmei establishing the capital of Heijō-kyō, present-day Nara, hence the name of the period. Except for a 5-year period (740 CE – 745 CE), when the capital was briefly moved again, it remained the capital of Nihon civilization until Emperor Kanmu established a new capital, Nagaoka-kyō, in 784 CE, before moving to Heian-kyō, modern Kyoto, a decade later in 794 CE.

The capital at Nara was modelled after Chang'an, the capital city of Táng dynasty. In many other ways, the Nihon upper classes patterned themselves after Zhōngguó, including adopting the Zhōngguó writing system, Zhōngguó fashion, and Zhōngguó Buddhism.

Religion and Temples:

During 6th century CE, Buddhism was introduced through official diplomatic channels to Mainland Nihon. Generally this introduction is attributed to Korean monks, primarily from Baekje kingdom, visiting Mainland Nihon.

With Buddhism, the reverence of images called Honzon started. The concept of a permanent shrine was introduced with Buddhism as well. A great number of Buddhist temples were built next to existing shrines in mixed complexes called Jingū-ji (神宮寺; shrine temple) to help priesthood deal with local deities, making those shrines permanent. Some time in their evolution, the word Miya (宮; palace), came into use indicating that shrines had by then become the imposing structures of today.

After the fall of Baekje (660 CE), the Yamato government sent envoys directly to the Zhōngguó’s court, from which they obtained a great wealth of Confucian philosophical and social structure. In addition to ethics and government, they also adopted the Zhōngguó’s calendar and many of its religious practices, including Confucianism and Taoism (Japanese: Onmyo).

Nara period saw the establishment of kokubunji system, which was a way to manage provincial temples through a network of national temples in each province. The head temple of the entire system was Tōdai-ji (completed in 752 CE).

During Nara period, immediately after the arrival of Buddhism in Nihon, bell towers were 3 × 2 bay, 2 storied buildings. A typical temple garan had normally two, one to the left and one to the right of the kyōzō (or kyō-dō), the sūtra repository. An extant example of this style is Hōryū-ji's Sai-in Shōrō in Nara.

→ Hōryū-ji's Sai-in Shōrō, an example of Nara period bell tower [Source: https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/9/9f/Horyuji-L0337.jpg]

Asuka bukkyō (552 CE – 645 CE):

Asuka bukkyō (Asuka-period Buddhism) refers to Buddhist practice and thought that mainly developed after 552 CE in Nara Basin region. Buddhism grew here through the support and efforts of two main groups: immigrant kinship groups like Hata clan (who were experts in Zhōngguó technology as well as intellectual and material culture), and through aristocratic clans like the Soga.

Some of the earliest structures still extant in Mainland Nihon are Buddhist temples established at this time. The oldest surviving wooden buildings in the world are found at Hōryū-ji, northeast of Nara, first built in early 7th century CE as the private temple of Crown Prince Shōtoku with the name Wakakusadera.

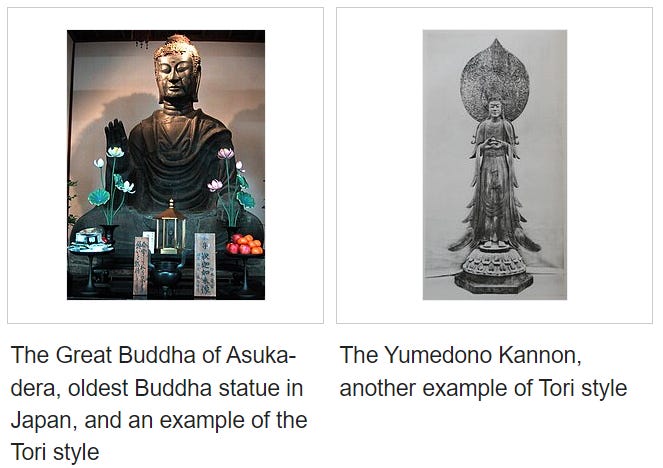

During this period, Buddhist art was dominated by the style of Tori Busshi4, who came from a Korean immigrant family. His style ultimately derives from that of Zhōngguó’s Tuòbá Wèi kingdom (386 CE – 535 CE). This style was intended for sculpting rock in caves, and even though Tori and his assistants sculpted in clay for bronze casting, his pieces reflect the Zhōngguó front-oriented design and surface flatness.

→ [Source: Screenshot from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Buddhism_in_Japan]

Hakuhō bukkyō (645 CE – 710 CE):

Under Hakuhō (referring to Emperor Tenmu) the official patronage of Buddhism being taken up by the Nihon imperial family, who replaced the Soga clan as the main patrons of Buddhism. Nihon Buddhism at this time was also influenced by Táng dynasty Buddhism.

It was also during this time that Buddhism began to spread from Yamato Province to the other regions and islands of Nihon.

An important part of the centralizing reforms of this era (Taika reforms) was the use of Buddhist institutions and rituals (often performed at the palace or capital) in the service of the state

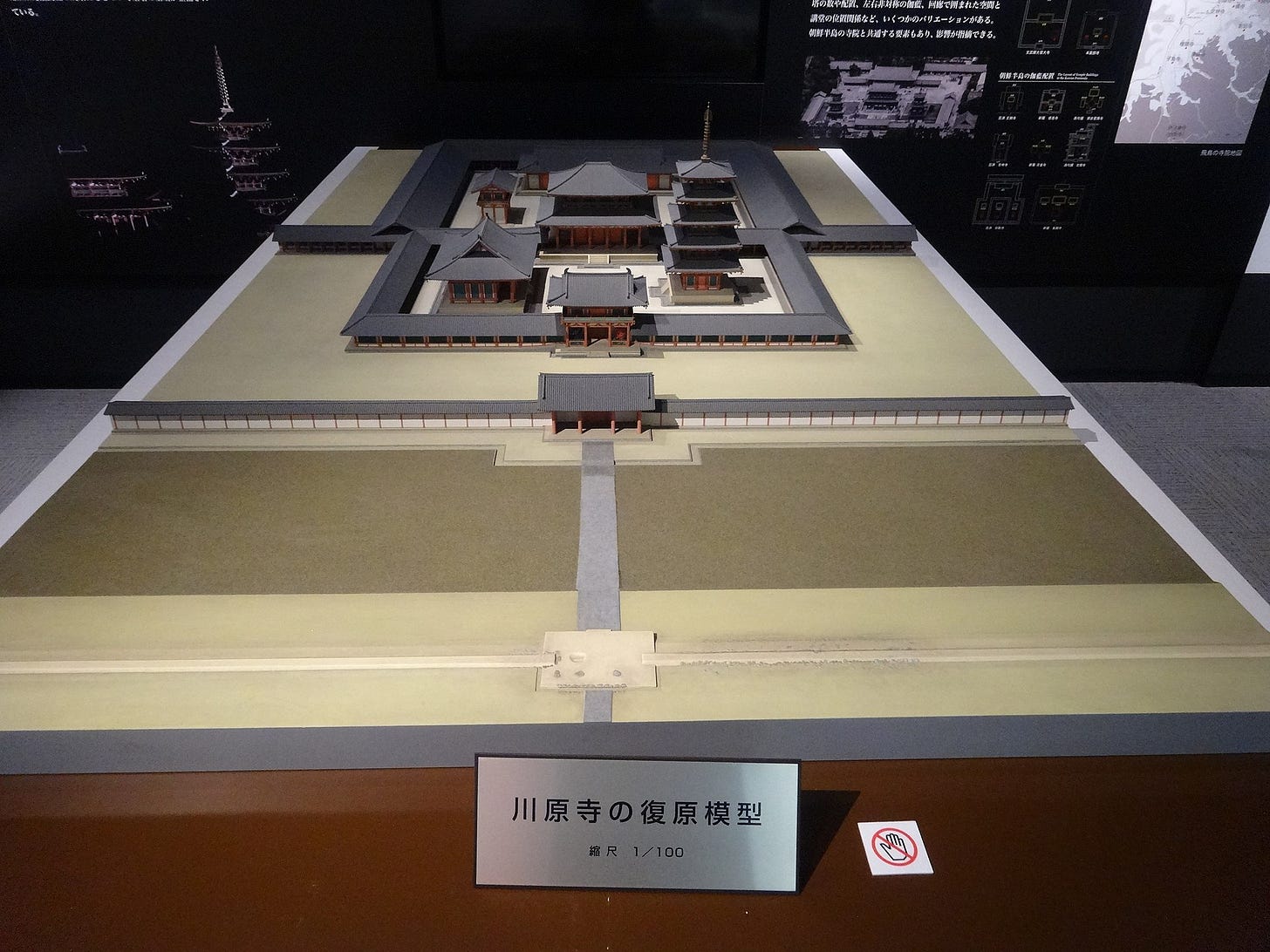

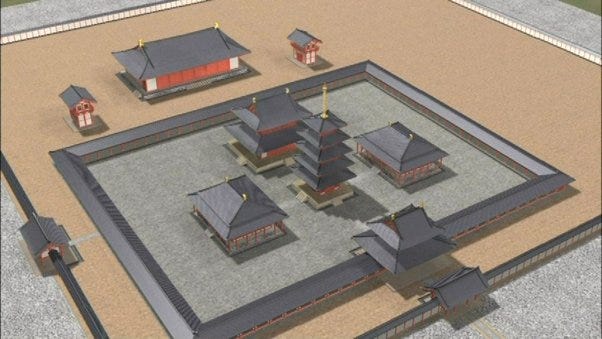

The imperial government actively built and managed the Buddhist temples as well as the monastic community. Some of these temples include Kawara-dera and Yakushi-ji.

Archaeological research also revealed numerous local and regional temples outside of the capital.

→

Model of Kawara-dera in Asuka Historical Museum, Japan [Source: https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/c/cf/Moel_of_Kawara_Temple.jpg/1920px-Moel_of_Kawara_Temple.jpg]

Model of Yakushi-ji [Source: https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/5/52/200730_Model_of_Yakushi-ji.jpg/1920px-200730_Model_of_Yakushi-ji.jpg]

8th century CE – 12th century CE

Heian period (794 CE – 1185 CE)

Polity:

During Heian period5, the capital was shifted to Kyoto (then known as Heiankyō) by emperor Kanmu, mainly for economic and strategic reasons.

Although Kōshitsu (Imperial House) had power on the surface, the real power was in the hands of the Fujiwara clan, a powerful aristocratic family who had intermarried with the imperial family. Many emperors had mothers from the Fujiwara family. The economy mostly existed through barter and trade, while the shōen system enabled the accumulation of wealth by an aristocratic elite. Even though Heian period was one of national peace, the government failed to effectively police the territory, leading to frequent robberies of travellers.

Zhōngguó’s influence on Nihon declined during this period. Huángcháo rebellion (874 CE – 884 CE)6 occurred in Zhōngguó against Táng dynasty making the political situation unstable. The planned Kentōshi (Nihon missions to Zhōngguó) were suspended and the influx of Zhōngguó exports halted, a fact which facilitated the independent growth of Nihon culture.

The period is also noted for the rise of the samurai caste, which eventually took over power and started the feudal period of Nihon.

Religion and Temples:

Early Heian Period Buddhism (794 CE – 950 CE)

Later Heian Period Buddhism (950 CE – 1185 CE)

This period saw some important developments taking place regarding both Shintō and Buddhist temple complexes in Mainland Nihon.

During this era, new Buddhist traditions began to develop. While some of these have been grouped into what is referred to as "new Kamakura" Buddhism, their beginning can actually be traced to the late Heian. This includes the practice of Nihon Pure Land Buddhism, which focuses on the contemplation and chanting of the nenbutsu, the name of the Buddha Amida (Amitābha), in hopes of being reborn in the Buddha field of Sukhāvatī. This practice was initially popular in Tendai monasteries but then spread throughout Japan.

In 905 CE, Emperor Daigo ordered a compilation of Shintō rites and rules. Previous attempts at codification are known to have taken place, but, neither Konin nor Jogan Gishiki survive. Initially under the direction of Tokihira of Fujiwara, the project stalled at his death in April 909 CE. Tadahira of Fujiwara, his brother took charge and in 912 CE, and in 927 CE Engi-shiki (延喜式 ; Procedures of Engi Era) was promulgated in 50 volumes. This, the first formal codification of Shintō rites and Norito (liturgies and prayers) to survive, became the basis for all subsequent Shintō liturgical practice and efforts.

→ Left to right: Emperor Daigo [Source: File:Emperor Daigo.jpg], Tokihira of Fujiwara [Source: File:Fujiwara no Tokihira01.jpg], Tadahira of Fujiwara [Source: File:Fujiwara no Tadahira.jpg]

Zhōngguó geomancy, that had influenced construction of Buddhist temple complexes in Nihon till then, lost in importance during Heian period as temple layout was adapted to the natural environment, disregarding feng shui.

During this period, the first of the 3 major Buddhist architecture styles of Nihon, Wayō emerged, being developed due to Michinaga of Fujiwara and retired Emperor Shirakawa competing in erecting new Buddhist temples. {The name was coined later during Kamakura period when the other two styles were born.}

Heian period also saw the development of tahōtō type Nihon pagodas. However, after Heian period, construction of pagodas in general declined

Heavy materials like stone, mortar and clay were abandoned as building elements, with simple wooden walls, floors and partitions becoming prevalent. Native species like cedar (sugi) were popular as an interior finish because of its prominent grain, while pine (matsu) and larch (aka matsu) were common for structural uses. Brick roofing tiles and a type of cypress called hinoki (Chamaecyparis obtusa) were used for roofs.

It was sometime during this period that Noyane (hidden roof), a uniquely Nihon solution to roof drainage problems, was adopted.

During this time the architectural style of Buddhist temples began to influence that of Shintō shrines:

Like their Buddhist counterparts Shintō shrines began to paint the normally unfinished timbers with the characteristic red cinnabar colour.

Stone Lanterns (Tōrō) began to used, sometime in this period, in Shintō shrines and private home; they were originally used only in Buddhist temples.

Also in 9th century CE, the tradition of keeping identical guardian animal figures changed and the 2 statues started to be different and be called differently: one had its mouth open and was called Shishi (獅子; lion), the other had its mouth closed and looked rather like a dog so was called Komainu (Goguryeo dog), and sometimes had a single horn on its head. Gradually the animals returned to be identical, but for their mouths, and ended up being called both Komainu.

12th century CE – 14th century CE

Kamakura Period (1185 CE – 1333 CE)

Northern Fujiwara clan independent rule (1087 CE – 1189 CE)

Kamakura bakufu (1192 CE – 1333 CE)

Actual shōgun rule (1192 CE – 1203 CE)

de facto Hōjō clan rule (1203 CE – 1333 CE)

Polities:

Kamakura period marked the governance by the Kamakura bakufu (Kamakura shogunate)7, officially established in 1192 CE in Kamakura by the first shōgun Minamoto no Yoritomo after the conclusion of Genpei War, which saw the struggle between the Taira and Minamoto clans. The period is known for the emergence of the samurai, the warrior caste, and for the establishment of feudalism in Nihon.

The authority to the Kamakura rulers waned in 1190s CE and power was transferred to the powerful Hōjō clan in early 13th century CE with the head of the clan as regent (Shikken) under the shōgun who became a powerless figurehead.

The later Kamakura period saw the invasions of the Mongols in 1274 CE and again in 1281 CE. To reduce the amount of chaos, the Hōjō rulers decided to decentralize power by allowing two imperial lines – Northern and Southern court, to alternate the throne. In the 1330s, CE the Southern court under Emperor Go-Daigo revolted and eventually led to the Siege of Kamakura in 1333 CE which ended the rule of the shogunate. With this, Kamakura period ended.

There was a short re-establishment (1333 CE – 1336 CE) of imperial rule under Go-Daigo assisted by Ashikaga Takauji and Nitta Yoshisada but would later lead to direct rule under Ashikaga, forming the Ashikaga shogunate in the succeeding Muromachi period.

Religion and Temples:

Kamakura Buddhism (1185 CE – 1333 CE) - new schools of Buddhism

There was an expansion of Buddhist teachings into Old Buddhism (Kyū Bukkyō) and New Buddhism (Shin Bukkyō). This period saw the development of new Buddhist lineages or schools which have been called "Kamakura Buddhism" and "New Buddhism". All of the major founders of these new lineages were ex-Tendai monks who had trained at Mt. Hiei and had studied the exoteric and esoteric systems of Tendai Buddhism. During Kamakura period, these new schools did not gain as much prominence as the older lineages, with the possible exception of Rinzai Zen school.

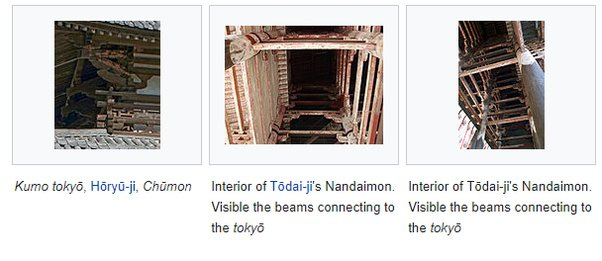

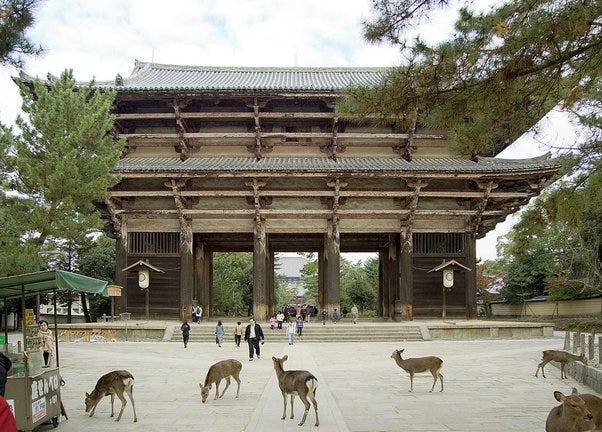

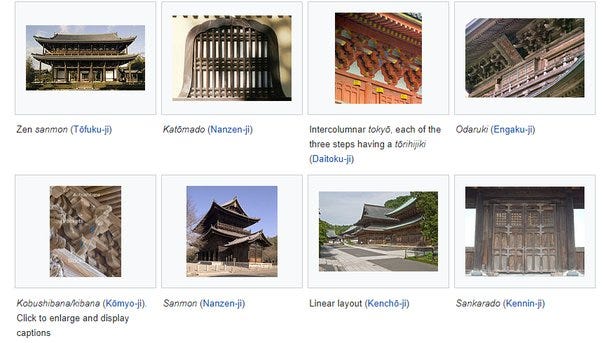

During Kamakura Period, the rest 2 major styles of Nihon Buddhist architecture were developed in response to native requirements such as earthquake resistance and shelter against heavy rainfall and the summer heat and sun by the master carpenters of this time: Daibutsuyō (Great Buddha Style) and Zenshūyo (Zen Style):

Daibutsuyō was introduced by the priest Chōgen in late 12th or early 13th century CE, based on Sòng Dynasty architecture, and represented the antithesis of the simple and traditional Wayō style. Nandaimon at Tōdai-ji and Amida Hall at Jōdo-ji are the only extant examples of this style. It was initially called Tenjikuyō (Indian style) but since it had nothing to do with India it was rechristened by scholar Ōta Hirotarō during 20th century CE.

This style didn’t adopte the hidden roofs.

→ Tōdai-ji's Nandaimon is one of the few extant examples of the daibutsuyō [Source: https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/b/b3/TodaijiNandaimon0185.jpg/1920px-TodaijiNandaimon0185.jpg]Zenshūyo was originally called Karayō (Chinese style) and was also rechristened by Ōta Hirotarō. Its characteristics are earthen floors, subtly curved pent roofs (mokoshi) and pronouncedly curved main roofs, cusped windows (katōmado) and panelled doors. Examples of this style include the belfry at Tōdai-ji, Founder's Hall at Eihō-ji and Shariden at Engaku-ji.

→ Kōzan-ji's butsuden in Shimonoseki, Japan. (Butsuden built 1320 CE) [Source: https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/0/04/Kozanji_Temple_%28Shimonoseki%29.JPG]

During this period, hōkyōintō type pagodas started to be made in stone and achieved their present form. They also started to be used as tombstones and cenotaphs during this period.

14th century CE – 16th century CE

Kenmu restoration (1333 CE – 1336 CE)

Muromachi period a.k.a. Ashikaga period (1336 CE – 1573 CE)

Ashikaga bakufu (1336 CE – 1573 CE)

Azuchi–Momoyama period (1568 CE – 1600 CE)

Polities:

The re-establishment of imperial power under Go-Daigo, known as Kenmu restoration (1333 CE – 1336 CE), alienated the samurai class, and Ashikaga Takauji deposed the emperor with their support. Ashikaga bakufu8 was thus established.

The third shōgun Ashikaga Yoshimitsu allowed the constables, who had had limited powers during the Kamakura period, to become strong regional rulers, later called daimyōs. In time, a balance of power evolved between the shōgun and the daimyōs; the three most prominent daimyō families rotated as deputies to the shōgun at Kyoto. Yoshimitsu was finally successful in reunifying the Northern and Southern courts in 1392 CE, but despite his promise of greater balance between the imperial lines, the Northern Court maintained control over the throne thereafter. The line of shoguns gradually weakened after Yoshimitsu and increasingly lost power to the daimyōs and other regional lords. The shōgun's influence on imperial succession waned, and the daimyōs could back their own candidates.

In time, the Ashikaga family had its own succession problems resulting in the outbreak of Ōnin War in 1467 CE, after which the power of the Ashikaga bakufu effectively collapsed, marking the start of the chaotic Sengoku period. In 1568 CE, Oda Nobunaga entered Kyoto to install Ashikaga Yoshiaki as 15th and ultimately final Ashikaga shōgun. This entrance marked the start of Azuchi-Momoyama period. This period ended with the Tokugawa victory at the Battle of Sekigahara in 1600 CE – unofficially establishing the Tokugawa Shogunate and beginning the Edo period.

Religion and Temples:

Late Medieval Buddhism (1336 CE – 1467 CE)

Late Muromachi-Period Buddhism (1467 CE – 1603 CE)

It is during this period that true lineages of "Shintō" kami worship begin to develop in Buddhist temples complexes, lineages which would become the basis for institutionalized Shintō of later periods. Buddhists continued to develop theories about the relationship between Kami, Buddhas and Bōdhīsattvas.

During Muromachi period, Wayō style was combined with Daibutsuyō and Zenshūyō to create Shin-Wayō and Setchūyō, and the number of temples in the pure Wayō style decreased after 14th century CE.

Setchūyō (eclectic style) developed from the fusion of elements from wayō, daibutsuyō and zenshūyō.

The combination of wayō and daibutsuyō, became so common that sometimes it is classed separately by scholars as Shin-wayō (new wayō).

→ Main hall (Built 1397 CE) of Totasan Kakurin-ji in Kakogawa, Hyōgo, Japan — this structure is an example of Setchūyō [Source: https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/e/ef/Kakurinji_Temple_Main_Hall_20150725.JPG/1920px-Kakurinji_Temple_Main_Hall_20150725.JPG]

Late Medieval Buddhism (1336 CE – 1467 CE):

During this period, the new "Kamakura schools" continued to develop and began to consolidate themselves as unique and separate traditions.

During the height of the medieval era, political power was decentralized and shrine-temple complexes were often competing with each other for influence and power. These complexes often controlled land and multiple manors, and also maintained military forces of warrior monks which they used to battle with each other.

During this period true lineages of "Shintō" kami worship begin to develop in Buddhist temples complexes, lineages which would become the basis for institutionalized Shintō of later periods. Buddhists continued to develop theories about the relationship between Kami, Buddhas and Bōdhīsattvas.

Late Muromachi-Period Buddhism (1467 CE – 1603 CE):

Beginning with the devastating Ōnin War (1467 CE – 1477 CE), the late Muromachi period saw the devolution of central government control and the rise of regional samurai warlords called daimyōs and the so called "warring states era" (Sengokuki). During this era of widespread warfare, many Buddhist temples and monasteries were destroyed, particularly in and around Kyoto. Many of these old temples would not be rebuilt until the 16th and 17th centuries CE.

This era also saw the rise of militant Buddhist leagues (ikki), like the Ikko Ikki ("Single Minded" Pure Land Leagues) and Hokke-ikki (Nichirenist "Lotus" Leagues), who rose in revolt against samurai lords and established self-rule in certain regions.

→ A model of Ishiyama Hongan-ji in Osaka, one of the main fortress-temple complex of Ikko-Ikki. [Source: https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/c/c5/%E5%A4%A7%E5%9D%82%E6%9C%AC%E9%A1%98%E5%AF%BA.jpg/1920px-%E5%A4%A7%E5%9D%82%E6%9C%AC%E9%A1%98%E5%AF%BA.jpg]

17th century CE – 19th century CE

Edo period (1603 CE – 1868 CE)

Tokugawa bakufu (1603 CE – 1868 CE)

Polities:

Tokugawa bakufu9 was established by Tokugawa Ieyasu after victory at the Battle of Sekigahara, ending the civil wars of the Sengoku period following the collapse of the Ashikaga shogunate. Ieyasu became the shōgun, and Tokugawa clan governed Nihon from Edo Castle in the eastern city of Edo (Tokyo) along with the daimyōs of the samurai class, hencem the name of this period as Edo Period10.

Tokugawa bakufu organized Nihon society under the strict Tokugawa class system and banned most foreigners under the isolationist policies of Sakoku to promote political stability. Tokugawa shōguns governed Nihon in a feudal system, with each daimyō administering a han (feudal domain), although the country was still nominally organized as imperial provinces. Under the Tokugawa shogunate, Japan experienced rapid economic growth and urbanization, which led to the rise of the merchant class and Ukiyo culture.

Tokugawa shogunate declined during the Bakumatsu period from 1853 CE and was overthrown by supporters of the Imperial Court in the Meiji Restoration in 1868 CE. Dai Nihon Teikoku (Empire of Japan) was established under the Meiji government, and Tokugawa loyalists continued to fight in Boshin War until the defeat of the Republic of Ezo at the Battle of Hakodate in June 1869 CE.

Religion and Temples:

Consequent to increased prosperity, Edo period was an era of unprecedented building fervour in religious architecture.

Traveling became popular among people due to the improvement of roads and post towns. The main destinations were famous temples and Shintō shrines around the country. The number of faithful coming for prayer or pilgrimage had increased, so designs changed to take into account their necessities.

Old sects limited themselves to revive old styles and ideas, while the new relied on huge spaces and complex designs. Both relied on heavy decorations on the temple complexes.

Conversely, the bussho ([Buddhist sculpture] workshops) disappeared entirely during this period.

→

Kiyomizu-dera in Kyoto, Japan (originally built 8th century CE, many structures added or rebuilt 17th century CE) [Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kiyomizu-dera]

Right to left: Kaisan-do (Founder's Hall), Kyo-do (Sutra Hall) and Sanju-no-to (Three storied Pagoda)

Sanju-no-to (Three storied Pagoda) and Niomon

Dǒugǒng

Dragon Sculpture

19th century CE – 20th century CE

Dai Nihon Teikoku / Japanese Empire (1868 CE – 1947 CE)

Polity:

Under Emperor Mutsuhito Japanese people moved from being an isolated feudal society at risk of colonisation by European powers to the new paradigm of a modern, industrialised nation state and emergent great power, influenced by Western scientific, technological, philosophical, political, legal, and aesthetic ideas.

Japan underwent a period of large-scale industrialization and militarization. These aspects contributed to Japan’s emergence as a great power following the First Sino-Japanese War, the Boxer Rebellion, the Russo-Japanese War, and World War I. Economic and political turmoil in 1920s CE, including the Great Depression, led to the rise of militarism, nationalism, statism and authoritarianism, and this ideological shift eventually culminated in Imperial Nihon joining the Axis alliance with Nazi Germany and Fascist Italy, and also conquering a large part of Asia-Pacific. During this period, Imperial Japanese Armed Forces committed numerous atrocities and war crimes.

Imperial Japanese Armed Forces initially achieved large-scale military successes during Second Sino-Japanese War and Pacific War. However, from 1942 onwards, Japan was forced to adopt a defensive stance against USA. The US American-led island-hopping campaign led to the eventual loss of many of Japan's Oceanian island possessions in the following 3 years. By August 1945, plans had been made for an Allied invasion of mainland Japan, but were shelved after Japan surrendered in the face of a major breakthrough by Western Allies and Soviet Union, with the atomic bombings of Hiroshima & Nagasaki and Soviet invasion of Manchuria. Pacific War officially came to an end on 2 September 1945, leading to the beginning of the Allied occupation of Japan. In 1947, through Allied efforts, a new Japan's constitution was enacted, officially ending the Japanese Empire and forming modern Japan. Reconstruction under the Allied occupation continued until 1952, consolidating the modern Japanese constitutional monarchy.

Religion and Temples:

Shintō shrines went through a massive change when Meiji administration promulgated a new policy of separation of kami and foreign Buddhas (shinbutsu bunri)11 with Kami and Buddhas Separation Order (神仏判然令, Shinbutsu Hanzenrei). This order triggered the haibutsu kishaku, a violent anti-Buddhist movement that caused the forcible closure of thousands of temples, the confiscation of their land, the forced return of many monks to lay life or their transformation into Shintō priests, and the destruction of numerous books, statues and other Buddhist artefacts. Even bronze bells were melted down to make cannons. However, the process of separation stalled by 1873 CE, the government's intervention in support of the order was relaxed, and even today the separation is still only partially complete: many major Buddhist temples retain small shrines dedicated to tutelary Shintō kami, and some Buddhist figures, such as the Bōdhīsattva Kannon (Guānyīn), are revered in Shintō shrines. The policy failed in its short-term aims and was ultimately abandoned, but it was successful in the long term in creating a new religious status quo in which Shintō and Buddhism are perceived as different and independent.

Nihon Style Temples began to appear at least since this period outside of Japan with Japanese diaspora establishing themselves in other nations.

→

Shingon Shu Hawaii in Honolulu, Hawaii, USA. It was first built in 1915-1918 CE by Nakagawa Katsutaro, a master builder of Japanese-style temples, then renovated in 1929 CE by Hego Fuchino, a self-taught man who was the first person of Japanese ancestry to become a licensed architect in the Islands. The building underwent further changes in 1978, and was considerably augmented in 1992 CE. [Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hawaii_Shingon_Mission]

Side view of main building — the roofs show yellow Hidari-mitsudomoe (left threefold tomoe) as decorative motifs

Lanterns, deities Fūjin (left) & Raijin (right), and statue of founder Kobo Daishi

Daifukuji Sōtō Mission in Mamalahoa Highway, Honalo, Hawaii, USA. Main hall was completed in 1921 CE, Japanese language school added in 1926 CE and Kannon Hall was added in 1937 CE. [Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Daifukuji_Soto_Zen_Mission]

20th century CE – present

Nihon-koku / Japan (1947 – present)

Polity:

In 1947, Japan adopted a new constitution emphasizing liberal democratic practices, becoming a constitutional monarchy with a bicameral legislature, the National Diet. Allied occupation ended with Treaty of San Francisco in 1952, and Japan was granted membership in United Nations in 1956.

Ryukyu islands remained under Japanese control although their traditional architecture was not completely supplanted by Nihon architecture.

Temples:

→

Byodo-In Temple Complex, replica of Byodo-In Temple Complex of Kyoto, in Valley of the Temples on the island of O'ahu in Hawai'i, USA (Built 1968 CE) [Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Byodo-In_(Hawaii)]

Jianzhen Memorial Hall in Dàmíng Temple Complex, Yangzhou, Jiangsu, PRC — the memorial hall, built in 1973 CE, was designed by Liang Sicheng modelled on the style of the Main Hall of Japan’s Tōshōdai-ji. Tōshōdai-ji itself was established by Zhōngguó‘s Táng Dynasty monk Jiànzhēn in 8th century CE. Therefore, the Jianzhen Memorial Hall is a Táng influences Nihon architecture example. [Source: https://travel.qunar.com/p-oi9017166-yangzhoudayunhewenhua]

Structural Details

Materials

Wood is the primary choice in various forms (planks, straw, tree bark, paper, etc.) for almost all structures. Unlike both Western and some Zhōngguó architecture, the use of stone is avoided except for certain specific uses, for example temple podia and pagoda foundations.

Wood

Commonly used native trees used to source wood include Matsu (Pine), Aka matsu (Larch), Sugi (Cedar), Hinoki (Chamaecyparis obtusa, a cypress species).

Hinoki

Hinoki (Chamaecyparis obtusa) is a species of cypress commonly used for roofing and building the structures.

Shintō Ise Shrine in Ise (Mie Prefecture, Japan) was originally constructed of locally sourced Hinoki wood, which served as an ideal building material due to its physical properties. The abundance of local Hinoki wood was short lived, and the shrine currently obtains the wood through other domestic producers.

→ Hinoki bark is used as a traditional roofing material at Tō-ji in Kyoto, Japan [Source: File:Kyoto Toji Hiwadabuki C0990.jpg]

Mokutō (木塔 ; wood pagoda)

Wooden multi-storey pagodas also have usually odd number of storeys, but some may appear to have an even number because of the presence of purely decorative enclosed pent roofs called mokoshi between the storeys.

Stone

Stone is relatively much less common in most structures.

Its use is mainly limited to bases of various structures, some types of Torii, some types of Tōrōs, and some types of Pagodas.

Sekitō (石塔 ; stone pagoda)

Sekitōs are usually made of materials like apatite or granite, are much smaller than wooden pagodas and are finely carved. Often they bear Saṁskr̥ta inscriptions, Buddhist figurines and Nihon lunar calendar dates nengō.

They are mostly classifiable on the basis of the number of stories as tasōtō or hōtō, but there are some styles rarely seen in wood: gorintō, muhōtō, hōkyōintō and kasatōba.

In case of Sekitōs, their sōrin (finial) is also made of stone

Kasatōba, Gorintō, Hōkyōintō and Muhōtō are mainly made from stone. They are mainly reliquaries or cenotaphs, and therefore unlikely to be the main pagoda of a temple complex.

For other types of pagodas, stone is not the primary element, but may be used to build them. Examples include smaller Hōtōs.

→ Sekitō examples:

Gorintō on top of the Mimizuka [Source: File:Mimizuka-M1773 corrected.jpg]

Hōkyōintō at Kōshū-ji in Fukuoka, Fukuoka Prefecture, Japan [Source: File:Hokyointo in Koshu-ji.jpg]

Muhōtō [Source: File:Engakuji Muhōtō.jpg]

Stone Kasatōba of Hannya-ji in Nara-City Nara Prefecture, Japan [Source: File:Hannyaji Stone Kasatoba.jpg]

Metal

Metal parts are rarely used in Nihon religious structures.

Bronze is commonly used to make temple bells, finials of wooden pagodas, and sometimes the small Sōrintō type pagodas themselves

Gateways

Mon (門; gate) is a generic Nihon term for gate often used, either alone or as a suffix, in referring to the many gates used by Buddhist temples, Shintō shrines and traditional-style buildings and castles.

Please note that the names have no relation to Digimons :).

They can be named after:

Their location, as chūmon (中門 ; intermediate gate) or of omotemon (表門 ; front gate) or karametemon (搦手門 ; back entrance gate).

The deity they house, as Niōmon (Niō gate: a gate enshrining two deities called Niō in its outer bays)

Their structure or shape, as nijūmon (two-story gate) or rōmon (tower gate)

Their function, as sanmon

Torii (鳥居 ; bird perch)

Torii or Toriimon is a traditional Nihon gate most commonly found at the entrance of or within a Shintō shrine, where it symbolically marks the transition from the mundane to the sacred.

The road leading to a Shintō shrine (sandō) is almost always straddled by >=one torii, which are therefore the easiest way to distinguish a shrine from a Buddhist temple. If the road passes under multiple torii, the outermost of them is called Ichi no torii (一の鳥居; first torii).

Torii may have originated as gateways made by posts connected by a rope tied between their tops.

→ [Source: holoholo.air-nifty.com]

→ Torii in the Hida Minzoku Mura Folk Village consisting of both rope connection and wooden beams [Source: File:Hidatorii.jpg - Wikimedia Commons]

In the past torii must have been used also at the entrance of Buddhist temples: Osaka's Shitennō-ji, a prominent Buddhist temple founded in 593 CE by Shōtoku Taishi and the oldest state-built Buddhist temple in the world, has a torii straddling one of its entrances (The original wooden torii burned in 1294 CE and was then replaced by one in stone). Many Buddhist temple complexes include >=1 Shintō shrines dedicated to their tutelary deity (called Chinjusha), and in that case a torii marks the shrine's entrance.

→ Stone torii of Shitennō-ji [Source: File:Shitennoji-torii.jpg - Wikimedia Commons]

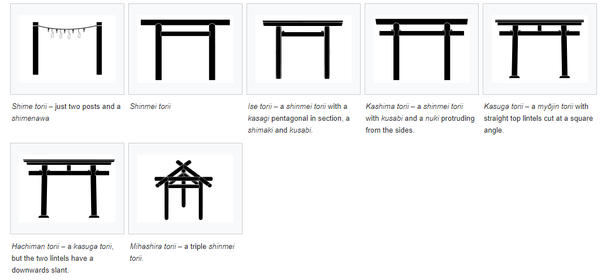

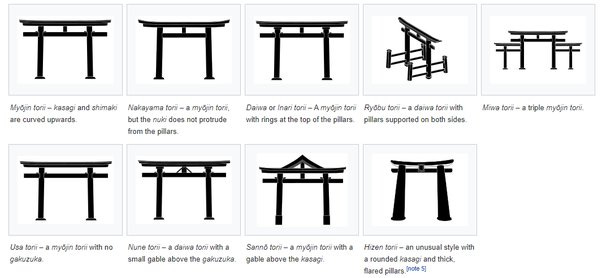

Types of Torii

shinmei family (神明系) : consist of only straight parts

myōjin family (明神系) : consist of both straight and curved parts

Shinmei family consists of following types of Torii [Source: Screenshot from Torii - Wikipedia]:

Myōjin family consists of following types of Torii [Source: Screenshot from Torii - Wikipedia]:

Parts of Torii

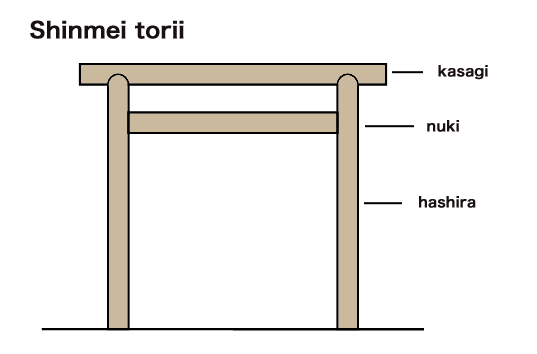

→ Shinmei Torii [Source: File:Shinmei torii.png]

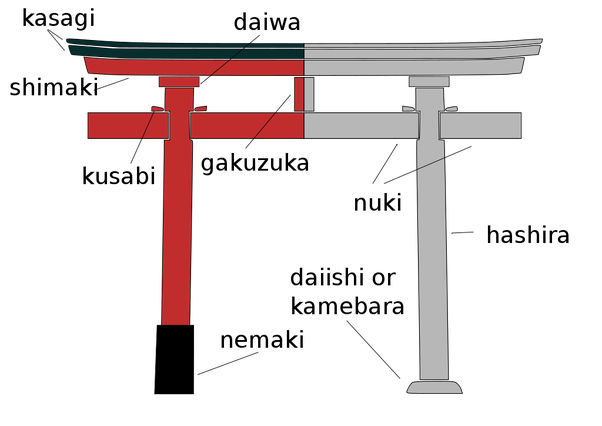

→ Myojin Torii [Source: File:Torii nomenclature.svg]

Shinmei Torii a.k.a. Futabashira Torii (二柱鳥居; “two pillar torii”) consists of just four unbarked and unpainted logs: two vertical pillars (hashira (柱)) topped by a horizontal lintel (kasagi (笠木)) and kept together by a tie-beam (nuki (貫)). The pillars may have a slight inward inclination called uchikorobi (内転び) or just korobi (転び). Its parts are always straight.

In general, a torii has following parts —

Hashira (柱) : vertical pillars, which may may a slight inclination called uchikorobi (内転び) or just korobi (転び)

Base of pillars : The pillars usually rest on a white stone ring called kamebara (亀腹; turtle belly) or daiishi (台石; base stone). The stone is sometimes replaced by a decorative black sleeve called nemaki (根巻; root sleeve).

At the top of the pillars there may be a decorative ring called daiwa (台輪; big ring).

Kasagi (笠木; horizontal lintel) and nuki (貫; tie-beam) :

The horizontal lintel is the topmost part of torii, which may be reinforced underneath by a second horizontal lintel called shimaki/shimagi (島木). Kasagi and Shimaki may have an upward curve called sorimashi (反り増し).

Nuki acts as the tie-beam, and supports Kasagi. It is often held in place by wedges (kusabi (楔)) which in most cases are ornamental.

At the center of nuki there may be a supporting strut gakuzuka (額束), sometimes covered by a tablet carrying the name of the shrine.

Torii may be left unpainted or are usually painted vermilion and black; the color black is limited to kasagi and nemaki.

Sōmon and Sanmon

Sōmon (総門 ; general gate)

It is the gate at the entrance of a Buddhist temple complex in Japan. It often precedes the bigger and more important sanmon.

→ [Source: File:Komyoji Main Gate.jpg]

Sanmon (三門 or 山門) a.k.a. Sangedatsumon (三解脱門 ; gate of the three liberations)

It is the most important gate of a Nihon Zen Buddhist temple, and is part of Zen shichidō garan, the group of buildings that forms the heart of a Zen Buddhist temple complex. It can be often found in temples of other denominations too. Most sanmon are 2- or 3-bay nijūmon (a type of two-storied gate), but the name by itself does not imply any specific architecture.

It usually stands between sōmon (outer gate) and the butsuden ("Hall of Buddha", i.e. the main hall). It used to be connected to a portico-like structure called Kairō (廻廊), which however gradually disappeared during Muromachi period, being replaced by the Sanrō (山廊), a small building present on both sides of the gate and containing a stairway to the gate's second story.

The sanmon's size is an indicator of a Zen temple's status:

Sanmon of a first rank temple as Nanzen-ji in Kyoto is a two-storied, 5x2 bay three entrance gate. Its three gates are called Kūmon (空門 ; gate of emptiness), Musōmon (無相門 ; gate of formlessness) and Muganmon (無願門 ; gate of inaction) and symbolize the three gates to enlightenment, or satori.

A temple of the second rank will have a two-storied, 3x2-bay, single entrance gate.

A third rank temple will have a single-storied, 1x2-bay, single entrance gate.

→ Sanmon of first, second and third rank. Sanmon in first image is a Nijūmon type by number of storeys. [Source: Sanmon-Wikipedia]

2-storey gates

There are in general, 2 types of 2-storeyed gates founds in Japan:

Nijūmon (二重門 ; two-story gate)

Rōmon (楼門 ; tower gate)

Nijūmon

Nijūmon has an accessible and usable upper storey and has a roof above the first floor which skirts the entire upper story. The second story of a nijūmon usually contains statues of Shakyamuni Buddha or of Kannon, and of the 16 Rakan, and hosts periodical religious ceremonies.

Of all temple gate types, the nijūmon has the highest status, and is accordingly used for important gates like Chūmon (middle gate) and Sanmon.

→ [Source: File:Kenchoji Gate.jpg]

Rōmon

Even though it was originally developed by Buddhist architecture, it is now used at both Buddhist temples and Shintō shrines. Its otherwise normal upper storey is inaccessible and therefore offers no usable space.

It was developed from nijūmon itself, replacing the flanking roof above the first floor with a very shallow balcony with a balustrade that skirts the entire upper storey.

In some cases, the rōmon of the complex itself houses the bell and is therefore is the bell tower.

→ Examples of regular Rōmon without bells:

[Source: File:Hannyaji Romon01.jpg]

[Source: https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/9/93/Udo_Jingu_Roumon.jpg]

→ Examples of regular Rōmon with bells:

A Rōmon Shōrō in Taipei, Taiwan. [Source: https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/3/3b/Taipei_City_Tone-Wa_Tample_Bell_tower.jpg/800px-Taipei_City_Tone-Wa_Tample_Bell_tower.jpg]

Tōrō (灯籠 or 灯篭, 灯楼 ; light basket, light tower)

It is a traditional lantern made of stone, wood, or metal. Like many other elements of Nihon traditional architecture, it originated in Zhōngguó where they can still be found in Buddhist temples and Zhōngguó gardens.

In Nihon, tōrō were originally used only in Buddhist temples, where they lined and illuminated paths. Lit lanterns were then considered an offering to Buddha. Their use in Shintō shrines and also private homes started during Heian period (794-1185 CE).

Types of light basket

Types of light basket (based on position):

Tsuri-dōrō (釣灯籠・掻灯・吊り灯籠 ; hanging lamp) a.k.a. kaitomoshi (掻灯) — small, four- or six-sided and made in metal, copper or wood. They usually hang from the eaves of a roof.

Dai-dōrō (台灯籠 ; platform lamp) — They are usually used in gardens and along the approach (sandō) of a shrine or temple. They are usually made of stone.

Types of Tōrō (based on material):

Kondō-dōrō (金銅燈籠 ; gilt bronze lantern) [usually hanging lanterns]

Ishi-dōrō (石灯籠 ; stone lantern) [usually platform lanterns]

Tachidōrō (立ち灯籠 ; pedestal lantern)

Kasuga-dōrō (春日灯籠)

Yūnoki-dōrō (柚ノ木灯篭)

Ikekomi-dōrō (活け込み燈籠 ; buried lantern)

Oribe-dōrō (織部灯籠)

Kirishitan-dōrō (キリシタン灯籠)

Mizubotaru-dōrō (水蛍燈籠)

Oki-dōrō (置き燈籠 ; movable lantern) — unfixed lantern resting on ground

Sankō-dōrō (三光灯籠)

Yukimi-dōrō (雪見燈籠 ; legged lantern) — base formed by one-six curved legs

Parts of light basket

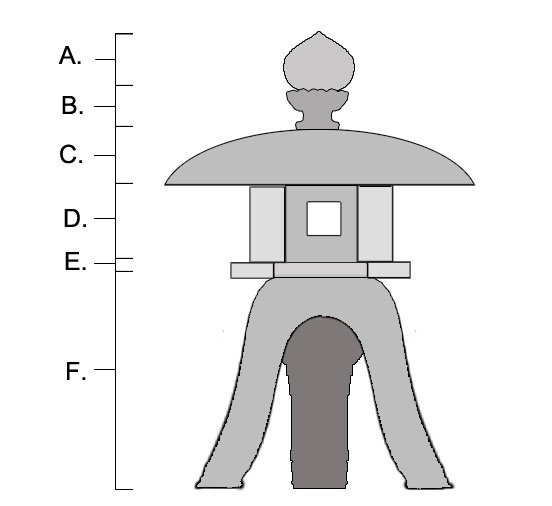

In any type of lantern, with the sole exception of the fire box, any parts may be absent.

→ A. Hōju or hōshu (宝珠 ; jewel), B. Ukebana, C. Kasa, D. Hibukuro, E. Chūdai, F. Sao {absent in hanging lanterns and movable lanterns} [Source: File:Diagram of a Japanese three-legged garden lamp.jpg]

Parts from top to bottom are as follows —

Hōju/hōshu (宝珠 ; jewel) : onion-shaped part at the very top of the finial

Ukebana (請花 ; receiving flower): lotus-shaped support of hōshu

Kasa (笠; umbrella) : conical or pyramidal umbrella covering the fire box. The corners may curl upwards to form the so-called warabide (蕨手). May be absent in movable lantern.

Hibukuro (火袋; fire sack) : fire box

Chūdai (中台 ; central platform) : platform for the fire box

Sao (竿 ; post) : the post, typically oriented vertically and either circular or square in cross-section, possibly with a corresponding "belt" near its middle; occasionally also formed as a sideways coin or disk, as a set of tall thin lotus petals, or as between one and four arched legs (in "snow-viewing" lanterns). Absent in hanging lantern and movable lantern.

Kiso (基礎 ; foundation) : base, usually rounded or hexagonal; absent in a buried lantern

Kidan (基壇; base platform) : variously shaped slab of rock sometimes present under the base

→ Hanging Lanterns [Source: Screenshot from Toro-Wikipedia]

→ Platform Lantern [Source: Screenshots from Toro-Wikipedia]:

Bronze lanterns

Stone Lanterns

Sandō (参道 ; visiting path)

It is the road approaching either a Shintō shrine or a Buddhist temple; with being straddled by Torii gateways in case of Shintō shrine.

A sandō is termed as follows:

omote-sandō (表参道; front sandō): main entrance {of it is now the only entrance road}

ura-sandō (裏参道; rear sandō): secondary point of entrance, especially to the rear

waki-sandō (脇参道; side sandō): side entrances, not a necessary feature

→

Sandō at Fushimi Inari Taisha in Kyoto, Japan — identifiable as reaching a Shintō shrine since it has torii [Source: File:Hushimi-inari-taisha omotesando.jpg]

Sandō to a Buddhist temple [Source: File:Ebaraji sanmon.jpg]

Sandō with stairs [Source: File:Taroubougu 3.JPG]

Roofs

Parts of Nihon Religious Complex Roofs

Chigi (千木, 鎮木, 知木, 知疑) and Katsuogi (鰹木, 堅魚木, 勝男木, 葛緒木)

Chigi (千木, 鎮木, 知木, 知疑), Okichigi (置千木) or Higi (氷木) are forked roof finials thought to have been employed on Nihon buildings starting from 1st century CE. Chigi may be built directly into the roof as part of the structure, or simply attached and crossed over the gable as an ornament. Chigi that aren't built into the building are crossed, and sometimes cut with a slight curve. While chigi are predominantly placed only at the ends of the roof, this method allows them to sometimes be placed in the middle as well.

Katsuogi (鰹木, 堅魚木, 勝男木, 葛緒木) or Kasoegi (斗木) are short, decorative logs between Chigi. It is usually a short, rounded log. Most are round, although square or diamond shapes have occasionally been used. Some are carved with tapered ends. More ornate katsuogi are covered in gold or bronze, and decorated with the clan symbol or motif.

→ [Source: File:Naiku 01crop.jpg]

Joints

Tokyō (斗栱・斗拱 or 斗きょう) a.k.a. Kumimono (組物) a.k.a. Masugumi (斗組):

Deriving from the Zhōngguó Dǒugǒng, it is a system of supporting blocks (斗 or 大斗, masu or daito, ; block or big block) and brackets (肘木, hijiki ; elbow wood) supporting the eaves of a Nihon building.

The use of tokyō is made necessary by the extent to which the eaves protrude, a functionally essential element of Nihon Buddhist architecture. The system has however always had also an important decorative function.

Types of tokyō :

In its simplest configuration, the bracket system has a single projecting bracket and a single block, and is called Hitotesaki. Repeating this generates some other types —

Futatesaki : first bracket and block group support a second similar one (2x hitotesaki)

Mitesaki : 3x hitotesaki

Yotesaki : 4x hitotesaki

Mutesaki : 6x hitotesaki

Sumisonae (隅備 or 隅具) or Sumitokyō (隅斗きょう) : brackets at the corner of a roof, having a particularly complex structure. The regular brackets between two sumisonae are called hirazonae (平備) or hiratokyou (平斗きょう).

Kumo tokyō (雲斗栱 ; cloud tokyō) : bracket system where the projecting bracket is shaped to resemble a cloud

Sashihijiki (挿肘木) : bracket arm inserted directly into a pillar instead of resting onto a supporting block on top of a pillar. Typical of Daibutsuyō.

→ [Source: File:Mutesaki tokyou.jpg]

Example images for Tokyō [Source: Screenshots from Tokyō-Wikipedia]

Tsumegumi (詰組)

These are intercolumnar supporting brackets, usually futatesaki or mitesaki, installed one immediately after the other. The result is an extremely compact row of brackets. Tsumegumi are typical of Zenshūyō.

→ Tsumegumi in main hall of Kenchō-ji in Kamakura, Kanagawa Prefecture, Japan [Source: File:Tsumegumi Butsuden Kenchouji.jpg]

Bell Tower and Bells

Shōrō / Shurō (鐘楼, bell building) or Kanetsuki-dō (鐘突堂 ; bell-striking hall) is a tower housing the temple complex’s Bonshō (梵鐘 ; Buddhist bell) a.k.a. Tsurigane (釣り鐘, hanging bells) or Ōgane (大鐘, great bell). They are primarily found in Nihon Buddhist Temple Complexes.

In some cases, the rōmon of the complex itself houses the bell and is therefore the bell tower.

Shōrō / Shurō (鐘楼, bell building) or Kanetsuki-dō (鐘突堂 ; bell-striking hall)

Shōrō / Shurō (鐘楼, bell building) or Kanetsuki-dō (鐘突堂 ; bell-striking hall)12 are of multiple styles, developed in different historical periods.

Bell Towers began mainly in Nara period after the arrival of Buddhism in Nihon. During Nara period, temple layout was rigidly prescribed after the Zhōngguó geomancy. But later on with the decline of Zhōngguó geomancy influence, the position of the bell tower stopped being prescribed and began to change temple by temple. Roofs are either gabled (切妻造, kirizuma-zukuri) or hip-and-gable (入母屋造, irimoya-zukuri).

During Nara period (710 CE – 794 CE), immediately after the arrival of Buddhism in Nihon, bell towers were 3 × 2 bay, 2 storied buildings. A typical temple garan had normally two, one to the left and one to the right of the kyōzō (or kyō-dō), the sūtra repository. An extant example of this style is Hōryū-ji's Sai-in Shōrō in Nara.

→ Hōryū-ji's Sai-in Shōrō, an example of Nara period bell tower [Source: https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/9/9f/Horyuji-L0337.jpg]

During the following Heian period (794 CE – 1185 CE) a new style was developed called Hakamagoshi which consisted of a two storied, hourglass-shaped building with the bell hanging from the second story. The earliest extant example is Hōryū-ji's Tō-in Shōrō.

→ Hōryū-ji's Tō-in Shōrō, a typical Hakamagoshi type [Source: https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/0/01/Horyu-ji37s3200.jpg/1920px-Horyu-ji37s3200.jpg]Finally, during 13th century CE the Fukihanachi type was created at Tōdai-ji by making all structural parts visible. The bell tower in this case usually consists of a 1-ken wide, 1-ken high structure with no walls and having the bell at its center. Sometimes the 4 pillars have an inward inclination called uchikorobi (内転び ; inward fall).

→ Tōdai-ji's bell tower, an example of the fukihanachi type, although much larger than the average [Source: https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/e/e9/Todaiji_shoro.jpg/1920px-Todaiji_shoro.jpg]

Bonshō (梵鐘 ; Buddhist bell) a.k.a. Tsurigane (釣り鐘, hanging bells) or Ōgane (大鐘, great bell)

Bonshō (梵鐘 ; Buddhist bell) a.k.a. Tsurigane (釣り鐘, hanging bells) or Ōgane (大鐘, great bell)13 are large bells found in Nihon Buddhist temples used to summon the monks to prayer and to demarcate periods of time. Rather than containing a clapper, bonshō are struck from the outside, using either a handheld mallet or a beam suspended on ropes.

The bells are usually made from bronze, using a form of expendable mould casting. They are typically augmented and ornamented with a variety of bosses, raised bands and inscriptions. The earliest of these bells in Nihon date to around 600 CE, although the general design is of much earlier Zhōngguó origin and shares some of the features seen in ancient Zhōngguó bells.

The bells' penetrating and pervasive tone carries over considerable distances, which led to their use as signals, timekeepers and alarms. In addition, the sound of the bell is thought to have supernatural properties; it is believed, for example, that it can be heard in the underworld.

Development

A Zhōngguó musical instrument termed Biānzhōng14 consists of a set of bronze bells, played melodically. Imported into various regions, it was termed pyeonjong in Korea, biên chung in Vietnam and henshō in Nihon.

One larger additional bell, which eventually developed into Bonshō, was used as a tuning device and a summons to listeners to attend a Biānzhōng recital. According to legend, the earliest Bonshō may have come from Zhōngguó to Nihon via Korean Peninsula: Nihon Shoki records that Nihon general Ōtomo no Satehiko15 brought 3 bronze bells back to Nihon in 562 CE as spoils of war from Goguryeo.

Construction

Bonshō are cast in a single piece using 2 moulds, a core and a shell, in a process that is largely unchanged since Nara period.

The core is constructed from a dome of stacked bricks made from hardened sand, whilst the shell is made using a strickle board. This is a large, flat, wooden board shaped like a cross-section of the bell, which is rotated around a vertical axis to shape the clay used for the mould.

Inscriptions and decorations are then carved or impressed into the clay.

The shell fits over the core to create a narrow gap, into which the molten bronze is poured at a temperature of over 1,050 °C (1,920 °F). The ratio of the alloy is usually around 17:3 copper to tin — the exact admixture (as well as the speed of the cooling process) can alter the tone of the end product. After the metal has cooled and solidified, the mould is removed by breaking it, therefore a new one has to be created for each bell.

The process has a high failure rate; only ~1/2 of the castings are successful on the first attempt, without cracks or imperfections.

Some bells retain linear impressions arising from joints in the mould used — they are not removed during fettling but are regarded as an aspect of the bell's overall beauty.

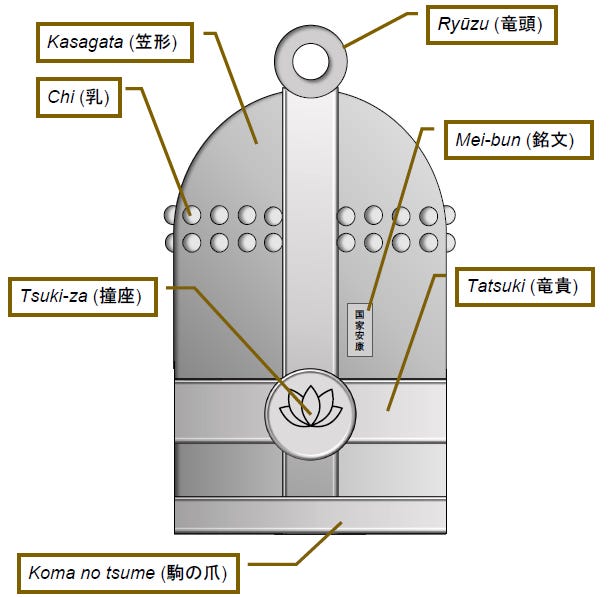

Parts of a Nihon temple bell

There are several parts to a temple bell:

Ryūzu (竜頭) : the dragon-shaped handle at the top of the bell, by which it is carried or hung

Kasagata (笠形) : the domed crown of the bell

Chi (乳) or nyū : bosses around the upper part of the bell that improve its resonance

Koma no tsume (駒の爪) : lower rim

Tsuki-za (撞座) : striking panel, a reinforced spot where the bell is struck. It is often decorated with a Buddhist lotus or chrysanthemum motif.

Tatsuki (竜貴) : decorative horizontal bands

Mei-bun (銘文) : inscription (often giving the bell's history)

Shu-moku (手木) : the hanging wooden beam used to strike the tsuki-za

→ [Source: https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/d/da/Bonsho_bits.png]

Sound

Bonshō are struck externally with either a hammer or a suspended beam.

The sound of the bell is made up of 3 parts:

First is the atari, the impact of the strike. A well-made bell should produce a clean, clear tone.

The initial sound of the strike is immediately followed by the prolonged oshi, the reverberation that continues to sound after the bell is struck. This is higher in pitch and is a low rumble with a sorrowful air, rich in harmonics. It lasts for up to 10 seconds.

Finally comes the okuri or decay, the resonance that is heard as the vibration of the bell dies away, which can last up to a minute.

There are also continuous harmonic overtones heard throughout the tolling of the bell. These multiple tones create a complex pitch profile.

The low tone and deep resonance of the bell allow the sound to carry over great distances; a large bonshō can be heard up to 32 km (20 miles) away on a clear day.

The pitch of the bell is carefully judged by its creators, and a difference of a single hertz in the fundamental frequency can require that the bell be recast from scratch.

Pagodas

Pagodas16 in Nihon are called tō (塔; pagoda) or tōba (塔婆, pagoda); a Buddhist Pagoda may be called buttō (仏塔, Buddhist pagoda). If they have >1 storey, they are called Tasōtō (多層塔; multi-storied pagoda) or Tajūtō (多重塔; multi-storied pagoda). With a few exceptions, they have an odd number of stories, usually 3-13.

Old pagodas had a stone base (心礎, shinso) over which stood the main pillar (心柱, shinbashira). Around it would be erected the first storey's supporting pillars, then the beams supporting the eaves and so on. The other stories would be built over the completed one, and on top of the main pillar would at last be inserted the finial. In later eras, all of the supporting structures would be erected at once, and later to them were fixed parts of more cosmetic function.

Early pagodas had a central pillar that penetrated deep into the ground. With the evolution of architectural techniques, it was first put to rest on a base stone at ground level, then it was shortened and put to rest on beams at the second storey to allow the opening of a room.

While common earlier when Buddhism had arrived, with the birth of new sects in later centuries, the pagoda lost importance and was consequently relegated to the margins of the garan. Their role within the temple declined gradually while they were being functionally replaced by main halls (kondō). Originally the centerpiece of the Shingon and Tendai garan, they were moved later to its edges and finally abandoned. Temples of the Jōdo sects rarely have a pagoda. During the Kamakura period the Zen sect arrived in Nihon and their temples do not normally include a pagoda.

Pagodas originally were reliquaries and did not contain sacred images, but in Nihon, many, for example Hōryū-ji's 5-storied pagoda, enshrine statues of various deities. To allow the opening of a room at the ground floor and therefore create some usable space, the pagoda's central shaft, which originally reached the ground, was shortened to the upper stories, where it rested on supporting beams. In that room are enshrined statues of the temple's main objects of worship. Inside Shingon pagodas there can be paintings of deities called Shingon Hasso (真言八祖); on the ceiling and on the central shaft there can be decorations and paintings.

Sekitō (石塔 ; stone pagoda):

Stone pagodas are usually made of materials like apatite or granite, are much smaller than wooden pagodas and are finely carved. Often they bear Saṁskr̥ta inscriptions, Buddhist figurines and Nihon lunar calendar dates nengō.

They are mostly classifiable on the basis of the number of stories as tasōtō or hōtō, but there are some styles rarely seen in wood: gorintō, muhōtō, hōkyōintō and kasatōba.

Mokutō (木塔 ; wood pagoda):

Wooden multi-storey pagodas also have usually odd number of storeys, but some may appear to have an even number because of the presence of purely decorative enclosed pent roofs called mokoshi between the storeys.

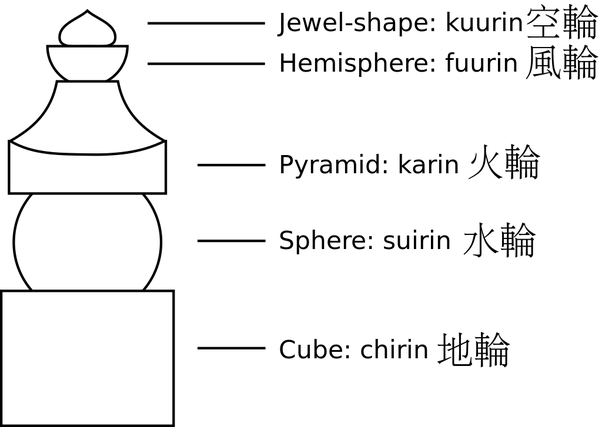

Gorintō (五輪塔; 5-ringed tower) OR gorinsotōba/gorinsotoba (五輪卒塔婆; 5-ringed stupa) OR goringedatsu (五輪解脱)

It is a stone pagoda used for memorial or funerary purposes, and is common in Buddhist temples and cemeteries.

In all its variations, the gorintō includes 5 rings, each having one of 5 shapes symbolic of Five Elements: earth ring (cube), water ring (sphere), fire ring (pyramid), air ring (crescent), and ether ring (jewel).

→ The 5 parts of Gorintō [Source: File:Pagoda.svg - Wikimedia Commons]

→ A gorintō on top of the Mimizuka [Source: File:Mimizuka-M1773 corrected.jpg]

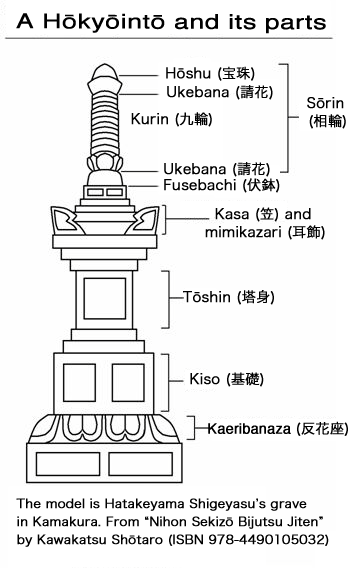

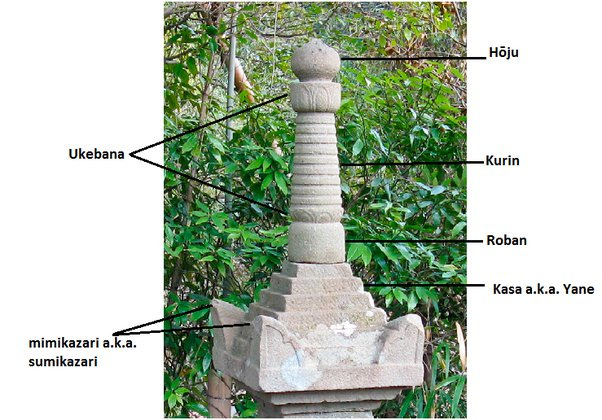

Hōkyōintō (宝篋印塔)

Hōkyōintō tradition in Nihon is believed to have begun during Asuka period. They used to be made of wood and started to be made in stone only during Kamakura period.

It was originally conceived as a cenotaph of Qian Liu, the king of Wuyue, in present day PRC, therefore, there are examples in China as well.

They have following parts:

kaeribanaza (反花座; inverted flower seat) : the lowermost portion

kiso (基礎; base) : rests on the inverted flower seat

tōshin (塔身; body)

kasa (笠; umbrella)

sōrin (相輪; pagoda finial)

→ [Source: File:Houkyouintou English.gif]

→ Hōkyōintō at Kōshū-ji in Fukuoka, Fukuoka Prefecture, Japan [Source: File:Hokyointo in Koshu-ji.jpg]

Muhōtō (無縫塔 ; no stitch tower) or Rantō (卵塔 ; egg tower)

It is a pagoda which usually marks the gravesite of a Buddhist priest. It was originally used by just the Zen schools, but it was later adopted by the others too.

→ [Source: File:Engakuji Muhōtō.jpg]

Kasatōba (笠塔婆 ; umbrella stupa)

It is simply a square stone post placed over a square base and covered by a pyramidal roof. Over the roof stand a bowl-shaped stone and a lotus-shaped stone. The shaft can be carved with Saṁskr̥ta words or low-relief images of Buddhist gods. Within the shaft there can be stone wheels which allow the faithful to turn the stupa around while praying as with a prayer wheel.

→ Stone Kasatōba of Hannya-ji in Nara-City Nara Prefecture, Japan [Source: File:Hannyaji Stone Kasatoba.jpg]

Sōrintō (相輪橖)

It is a small pagoda consisting just of a pole and a sōrin.

→ [Source: File:Hitsujisaki jinja Sourintou.JPG]

Hōtō (宝塔; treasure pagoda), Tahōtō (多宝塔; many-jewelled pagoda) and Daitō (大塔; large pagoda)

Hōtō is the ancestor of tahōtō and dates to the introduction to Nihon of Shingon and Tendai Buddhism in 9th century CE. No wooden hōtō has survived, albeit modern copies do exist, and stone, bronze, or iron specimen are always miniatures comprising a foundation stone, barrel-shaped body, pyramid roof, and a finial.

→ Hōtō examples:

Hōtō in Ankokuron-ji, Kamakura, Kanagawa, Japan [Source: File:Houtou - Ankokuron-ji.jpg]

Hōtō of Ikegami Honmon-ji Temple Complex in Tokyo, Japan [Source: File:Ikegami Honmon-ji hōtō.jpg]

Tahōtō

Tahōtō is unique among Nihon style pagodas because it has an even number of stories (two). {The second story has a balustrade and seems habitable, but is nonetheless inaccessible and offers no usable space.} It has square lower and cylindrical upper parts, a mokoshi (skirt roof), a pyramidal roof, and a sōrin (finial).

Raised over the kamebara (亀腹; tortoise mound), the ground floor has a square plan, 3x3 ken across, with a circular core. Inside, a room is marked out by shitenbashira (四天柱; four pillars of heaven), a reference to Four Heavenly Kings. The main objects of worship are often enshrined within.

Above is a second 'tortoise mound', in a residual reference to the stupa. Exposed plaster weathers rapidly so a natural solution was to provide it with a roof, the mokoshi. Above again is a short, cylindrical section and a pyramidal roof, supported on four-stepped brackets.

→ Tahōtō examples:

Tahōtō at Ishiyama-dera, dating to 1194 CE [Source: File:Ishiyamadera29n4272.jpg - Wikimedia Commons]

Daitō

Daitō is a larger 5x5 ken version. This is the only type of tahōtō to retain the original structure with a row of pillars or a wall separating the corridor (hisashi) from the core of the structure, abolished in smaller pagodas.

→ Narita-san (Great Pagoda of Peace) in Narita, Chiba Prefecture, Japan [Source: File:Narita-san Great Pagoda of Peace.JPG]

Sotōba (卒塔婆)

It is a strip of wood, sometimes stone, shaped like a gorintō laid as an offer on tombs in Nihon. It is divided in 5 sections representing the 5 elements of Buddhism cosmology, and carries inscriptions in Saṁskr̥ta and Japanese. Below these follows the deceased person's posthumous name. Their name derives from Saṁskr̥ta word stūpa, and they are considered pagodas.

→ Graves in Ogo, Kobe, Hyogo prefecture, Japan [Sourcce: File:2013-01-05 Wood stûpa Graves in Ogo,Kobe,Hyogo prefecture 神戸市北区淡河町の墓地と木製卒塔婆 DSCF4046.JPG]

→ Stone Sotōba [Source: File:山鹿素行墓(宗参寺).JPG - Wikimedia Commons]

Parts of a Nihon Pagoda

Sōrin (相輪 ; alternate rings)

Sōrin17 is the vertical shaft (finial) which usually tops a Nihon pagoda, whether made of stone or wood. The finial of a wooden pagoda is usually made of bronze and can be >10m tall while that of a stone pagoda is also of stone and <1m long.

The finial is supported by a long shaft, often obtained by joining two or three shorter ones, that runs to the base of the edifice. The pillar at the core of a Japanese pagoda serves the sole purpose of supporting the long and heavy bronze finial.

→ Parts of bronze finial [Source: File:Tenneiji Onomichi03s3200-Sourin.jpg]

→ Parts of stone finial [Source: File:Houkyouintou-sourin.jpg - Wikimedia Commons]

Objects to house deities

Yorishiro (依り代・依代・憑り代・憑代)

A yorishiro in Shintō terminology is an object capable of attracting spirits/deities called kami, thus giving them a physical space to occupy during religious ceremonies. Yorishiro are used during ceremonies to call the deity for worship. The word itself literally means approach substitute.

Once a yorishiro actually houses a deity, it is called a shintai (神体, "body of the kami"), or go-shintai (御神体, "sacred body of the kami").

Ropes called shimenawa (標縄/注連縄/七五三縄, 'enclosing rope') decorated with zig-zag paper streamers called shide (紙垂, 四手) often surround yorishiro to make their sacredness manifest.

→ A giant tree yorishiro transformed into shintai, and indicated by shimenawa decorated with shide [Source: File:Yuki Shrine - giant Sugi.jpg]

The most common yorishiro are:

swords

mirrors

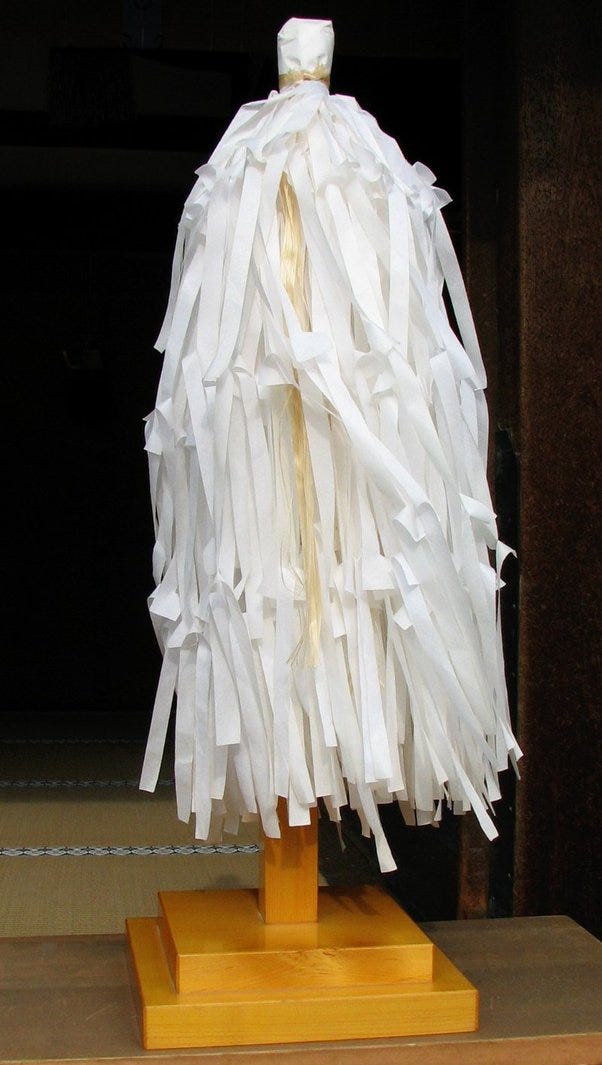

Ōnusa (大幣) or simply nusa (幣) : ritual staffs decorated with paper streamers called gohei (御幣)/onbe (御幣)/heisoku (幣束)

comma-shaped jewels called magatama (勾玉 or 曲玉)

iwasaka (岩境) or iwakura (磐座): large rocks

sacred trees, OR in case of altar (called Himorogi (神籬; "divine fence")), a branch of Sakaki tree

yorimashi (憑坐): persons

→ Nusa [Source: File:Shinto Onusa.jpeg]

→ Gohei [Source: File:Shinto gohei.jpeg]

→ A himorogi at Tsurugaoka Hachiman-gū [Source: File:Tsurugaoka hachimangu himorogi.jpg]

Honzon (本尊 ; fundamental honored [one]))

Honzon, reverentially called Gohonzon, is the enshrined main image or principal deity in Japanese Buddhism. The Buddha, Bōdhīsattva, or Maṇḍala image is located in either a temple or a household butsudan.

The physical creation of an icon is followed by a consecration ceremony (known as kaigen; 'opening the eyes' or 'dotting the eyes'). It is believed this transforms the honzon into a 'vessel' of the deity which in its own right has power.

→ Shingon-shu Buzan-ha Mikkyo altar [Source: File:Shingon Altar Ming Ya Buddhist Foundation of L.A., 2010.jpg]

Butsuzō (仏像)

A honzon that takes the form of a statue, usually crafted out of cypress wood or metal such as copper or bronze. Butsuzō is more common than other types of images.

→ An example of Butsuzō Honzon in the Pure Land tradition featuring Amida Buddha [Source: File:Amida Nyorai.jpg]

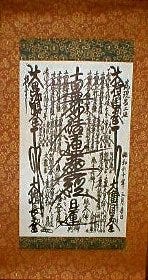

Kakejiku OR moji-mandara (文字曼荼羅 ; script mandala)

It is the primary object of devotion in Nichiren Buddhist schools. It is written in traditional kanji characters with the addition of 2 Siddhaṃ scripts.

→ Gohonzon inscribed by Nikken Abe used by the Nichiren Shoshu school [Source: File:Nichiren Shoshu Gohonzon.jpg]

Sanctums/Nearly equivalent structures

Kamidana (神棚 ; deity/spirit-shelf)

Its is miniature household altar provided to enshrine a Shintō deity.

The kamidana is typically placed high on a wall and contains a wide variety of items related to Shintō-style ceremonies, the most prominent of which is the shintai, an object meant to house a chosen kami, thus giving it a physical form to allow worship. Kamidana shintai] are most commonly small circular mirrors, though they can also be stones (magatama), jewels, or some other object with largely symbolic value.

The deity within the Shintai is often the deity of the local shrine or one particular to the house owner's profession. A part of the deity (called bunrei) was obtained specifically for that purpose from a shrine through a process called kanjō.

→ [Source: File:Kamidana.jpg - Wikimedia Commons]

Butsudan (仏壇 ; Buddhist altar) OR Butudan

It is a shrine commonly found in temples and homes in Japanese Buddhist cultures. Its primary use is for paying respects to the Buddha, as well as to family members who have died.

A butsudan usually contains an array of subsidiary religious accessories, called butsugu, such as candlesticks, incense burners, bells, and platforms for placing offerings such as fruit, tea or rice. Some Buddhist sects place ihai memorial tablets, kakochō death registers for deceased relatives, or urns containing the cremated remains of relatives, either within or near the butsudan.

The defined space which occupies the Butsudan is referred to as Butsuma.

If there are doors used, a Butsudan enshrines Honzon icon during religious observances, and close after usage.

In case of no doors, either a sheet of brocade or white cloth is sometimes placed over to render its sacred space.

Nihon Shintō Temple Complex

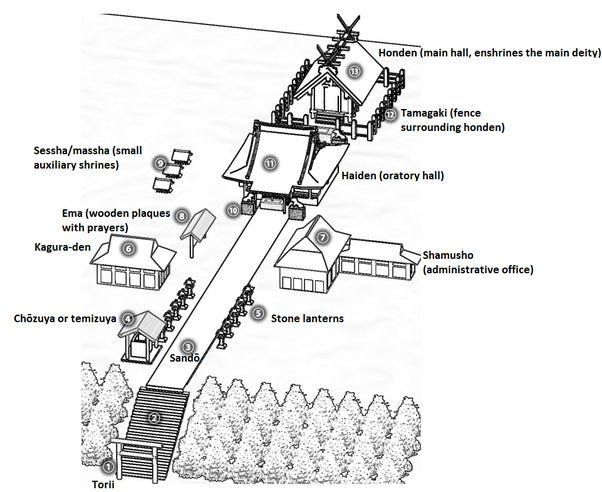

→ Labelled diagram of a general Shintō complex. No 2 is simply the flight of stairs to the temple, No10 represents the “guardian lions” of the temple [Source: File:Plan of Shinto Shrine.jpg]

The parts Torii, Sandō, and Tōrō have been already covered above.

Nihon Shintō Temple Architecture Styles

Ishi-no-ma-zukuri (石の間造) a.k.a. gongen-zukuri (権現造) a.k.a. yatsumune-zukuri (八棟造) a.k.a. miyadera-zukuri (宮寺造)

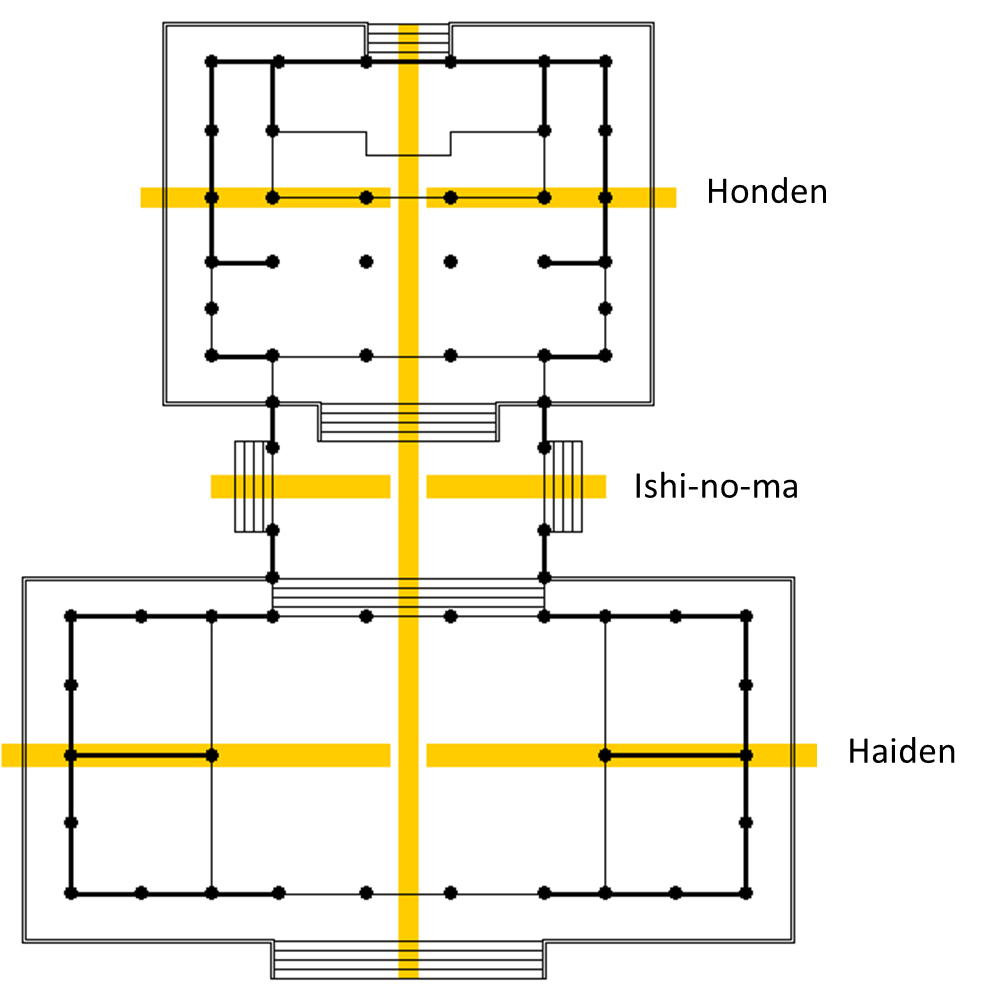

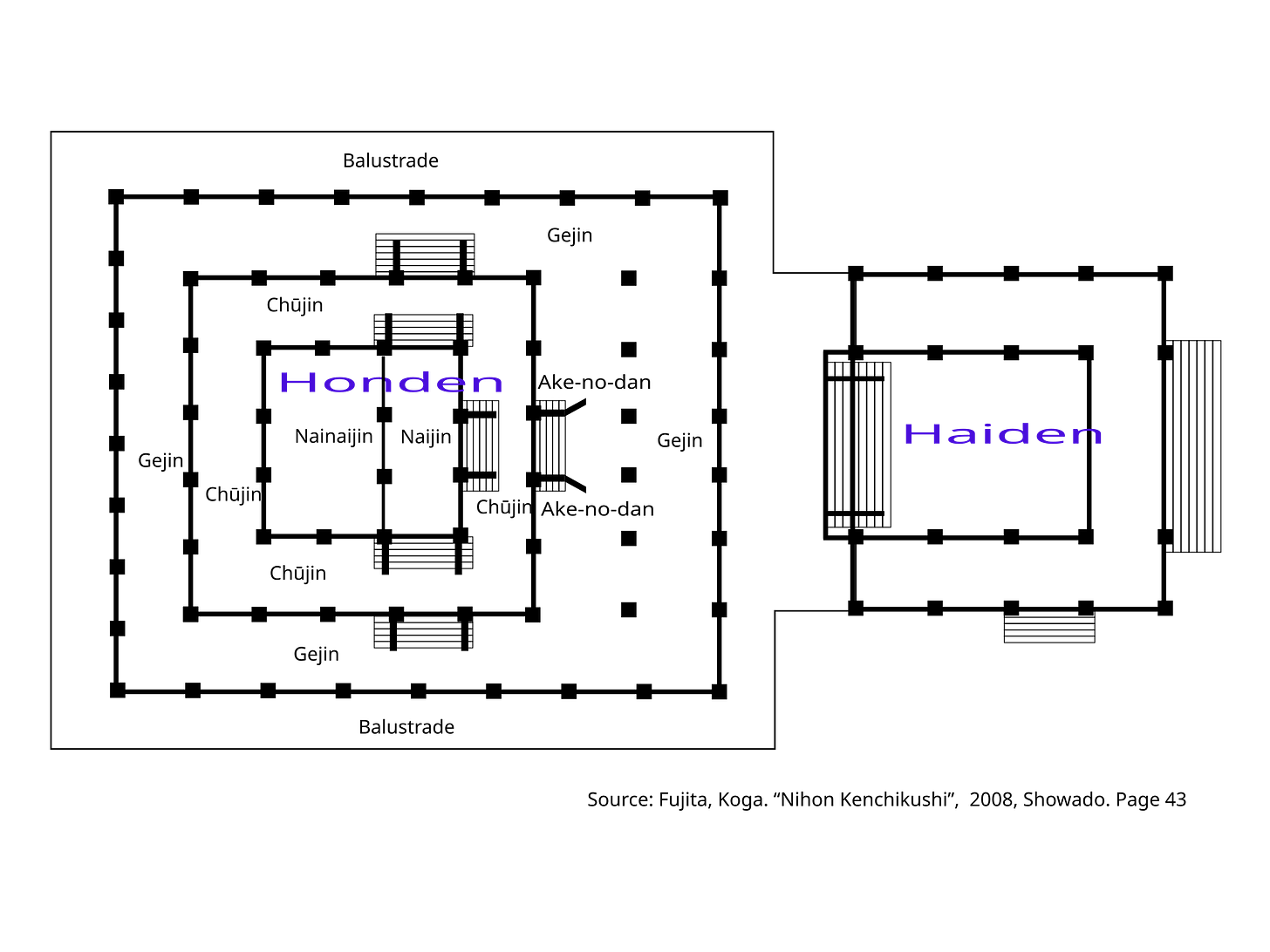

Ishi-no-ma-zukuri (石の間造) a.k.a. gongen-zukuri (権現造) a.k.a. yatsumune-zukuri (八棟造) a.k.a. miyadera-zukuri (宮寺造)18 is a Nihon Shintō shrine structure in which the haiden and honden are interconnected under the same roof in the shape of an H.

The connecting passage can be called ai-no-ma (相の間), ishi-no-ma (石の間), or chūden (中殿 ; intermediate hall). The floor of each of the three halls can be at a different level. If the ai-no-ma is paved with stones it is called ishi-no-ma, which gives the name of the style; however the path may be paved with planks or tatami. Its width is often the same as the honden's, with the haiden being one to three ken wider.

This style defines the relationship between member structures of a shrine rather than the structure of a building. Therefore, different structures can belong to same or different architecture styles.

→ A gongen-zukuri shrine. From the top: honden, ishi-no-ma, haiden. In yellow are the ridges of the roofs [Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ishi-no-ma-zukuri#/media/File:Gongen_Zukuri.png]

Hirairi-zukuri (平入・平入造)

Hirairi-zukuri (平入・平入造)19 is a Nihon Shintō architectural structure where the building has its main entrance on the side which runs parallel to the roof's ridge (non gabled-side). Shinmei-zukuri, nagare-zukuri, hachiman-zukuri, and hie-zukuri Shintō architectural styles belong to this type.

Shinmei-zukuri (神明造)20 exemplified by Nishina Shinmei Shrine is characterized by an extreme simplicity. Its basic features can be seen in Nihon architecture from Kofun period (250 CE – 538 CE). Built in plane-unfinished wood, the honden is either 3×2 ken or 1×1 ken in size, has a raised floor, a gabled roof with an entry on one of the non-gabled sides, no upward curve at the eaves, and purely decorative logs called chigi (vertical) and katsuogi (horizontal) protruding from the roof's ridge

→ Building with Chigi and Katsuogi visible over roof, in Nishina Shinmei Shrine in Ōmachi, Nagano Prefecture, Japan. [Source: https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/3/33/Nishina_Shinmei_Shrine-Honden.jpg

Nagare-zukuri (流造 ; streamlined roof style) a.k.a. nagare hafu-zukuri (流破風造 ; streamlined gabled style)21 characterized by a very asymmetrical gabled roof (kirizuma-yane (切妻屋根)) projecting outwards on one of the non-gabled sides, above the main entrance, to form a portico — this feature gives the style its name.

→ Ujigami Shrine in Uji, Kyoto Prefecture, Japan [Source: https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/5/57/Ujigami_jinja08s3s4500.jpg/1920px-Ujigami_jinja08s3s4500.jpg]

Ryōnagare-zukuri (両流造 ; double streamlined roof style) is an evolution of the nagare-zukuri in which the roof flows down to form a portico on both non-gabled sides.

→ Haiden of Itsukushima-jinja in Hatsukaichi, Hiroshima Prefecture, Japan [Source: https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/b/b0/Itsukushima_Honden_Haiden.jpg]

Hachiman-zukuri (八幡造)22 consists of 2 parallel structures with gabled roofs interconnected on the non-gabled side, forming one building which, when seen from the side, gives the impression of 2. The front structure is called gaiden (外殿 ; outer sanctuary), the rear one naiden (内殿 ; inner sanctuary), and together they form the honden. The honden itself is surrounded by a cloister-like covered corridor called kairō (回廊).

Hiyoshi-zukuri a.k.a. hie-zukuri (日吉造), also called shōtei-zukuri / shōtai-zukuri (聖帝造) or sannō-zukuri (山王造)23 is It is characterized by a hip-and-gable roof with verandas called hisashi on the sides. The building is composed of a 3×2 ken core called moya surrounded on 3 sides by a 1-ken wide hisashi, totaling 5×3 ken. The three-sided hisashi is unique and typical of this style. The gabled roof extends in small porticos on the front and the two gabled sides. The roof on the back has a characteristic shape (see below images).

It is a rare Shintō shrine architectural style presently found in only 3 instances, all at Hiyoshi Taisha in Ōtsu, Shiga, hence the name. They are the East and West Honden Hon-gū and Sessha Usa Jingū Honden.

→ Hiyoshi Taisha [Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hiyoshi-zukuri]

Hiyoshi Taisha's Higashi Hon-gū

The typical shape of the back of a Hiyoshi-zukuri roof

Tsumairi-zukuri (妻入・妻入造)

Tsumairi-zukuri (妻入・妻入造) is Nihon Shintō architectural structure where the building has its main entrance on one or both of the gabled sides (妻 ; tsuma). Kasuga-zukuri, taisha-zukuri, and sumiyoshi-zukuri architectural styles belong to this type.

Kasuga-zukuri (春日造)24 , which takes its name from Kasuga Taisha's honden, is characterized by the use of a building just 1×1 ken in size with the entrance on the gabled end covered by a veranda. Supporting structures are painted vermilion, while the plank walls are white. The roof is gabled (kirizuma yane (切妻屋根, gabled roof)), decorated with purely ornamental poles called chigi (vertical) or katsuogi (horizontal), and covered with Hinoki bark. Shrines with a kasuga-zukuri honden are found mostly in Kansai region around Nara.

If a sumigi (隅木 ; diagonal rafter) is added to support the portico, the style is called sumigi-iri kasugazukuri (隅木入春日造).

→ The honden at Uda Mikumari Shrine Kami-gū is made of three joined Kasuga-zukuri buildings [Source: https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/a/aa/Udamikumari_Shr_Kami_detail.jpg]

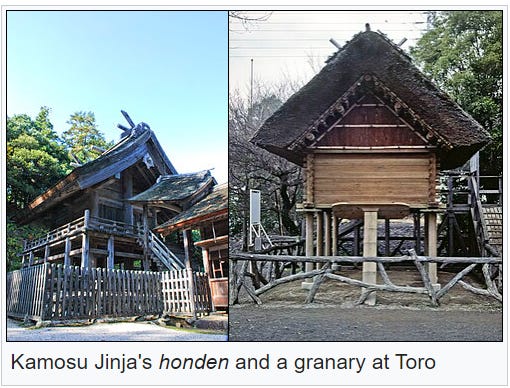

Taisha-zukuri a.k.a. Ōyashiro-zukuri (大社造)25 , named after Izumo Taisha's honden, is the oldest Shintō shrine architectural style.

Izumo Taisha's honden features a bark roof decorated with poles called chigi and katsuogi, plus archaic features like gable-end pillars and a single central pillar (shin no mihashira). Its interior is a square divided into four identical sections, each covered by fifteen tatami (straw mats). The floor plan has therefore the shape of the Chinese character for rice field (田), an element which suggests a possible connection with harvest propitiation rites. As its floor is raised above the ground, the honden is believed to have its origin in raised-floor granaries like those found in Toro, Shizuoka prefecture.

→ [Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Taisha-zukuri]

Izumo Taisha's honden

Kamosu Shrine’s honden, built 16th century CE, represents an older variant of Taisha-zukuri

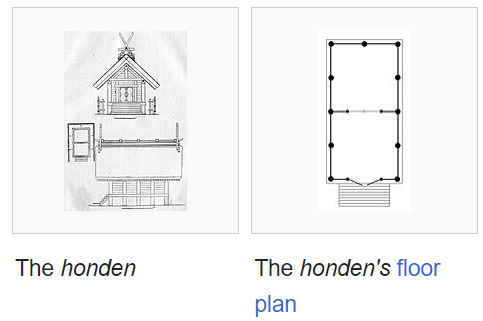

Sumiyoshi-zukuri (住吉造) takes its name from Sumiyoshi Taisha's honden.

The 4 identical buildings that compose Sumiyoshi Taisha's honden are 4 ken wide and 2 ken deep and have an entrance under one of the gables (a characteristic called tsumairi-zukuri (妻入造). The roof is simple, doesn't curve upwards at the eaves and is decorated with purely ornamental poles called chigi (vertical) and katsuogi (horizontal). The building is surrounded by a fence called mizugaki (瑞垣), in its turn surrounded by another called tamagaki (玉垣). There is no veranda, and a short stairway leads to the door.

The interior is divided in two sections, one at the front (gejin (外陣)) and one at the back (naijin (内陣)) with a single entrance at the front (see floor plan in the gallery). The structure is simple, but brightly colored: supporting pillars are painted in vermilion and walls in white.

This style is believed to have its origin in old palace architecture.

→ [Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sumiyoshi-zukuri]

Sumiyoshi Taisha's Funatama Jinja

Sumiyoshi Taisha's honden & honden’s floorplan

Kibitsu-zukuri (吉備津造) a.k.a. kibi-zukuri (吉備造) a.k.a. hiyoku irimoya-zukuri ([入母屋造])

Kibitsu-zukuri (吉備津造) a.k.a. kibi-zukuri (吉備造) a.k.a. hiyoku irimoya-zukuri ([入母屋造])26 is characterized by 4 dormer gables, 2 per lateral side, on the roof of a very large honden. The gables are set at a right angle to the main roof ridge, and the honden is part of a single complex also including a haiden (worship hall).

Kibitsu Jinja in Okayama is the sole example of the style, and gives the style its name. It was built in 14th century CE under 3rd Ashikaga shōgun Ashikaga Yoshimitsu

→ [Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kibitsu-zukuri]

Kibitsu Jinja’s honden-haiden complex. The main entrance (hidden) is on the right

Kibitsu Jinja’s floorplan

General Parts of a Nihon Shintō Temple Complex

Chōzu-ya or temizu-ya (手水舎, ちょうずしゃ、てみずしゃ)

It is a Shintō water ablution pavilion for a ceremonial purification rite known as temizu/chōzu (手水; hand-water). The pavilion contains a large water-filled basin called chōzubachi (手水鉢; hand water basin).

→ [Source: File:Make-jinja Shrine - Chôzuya.jpg]

→ [Source: File:Isejingu Shogu Geku-6.jpg]

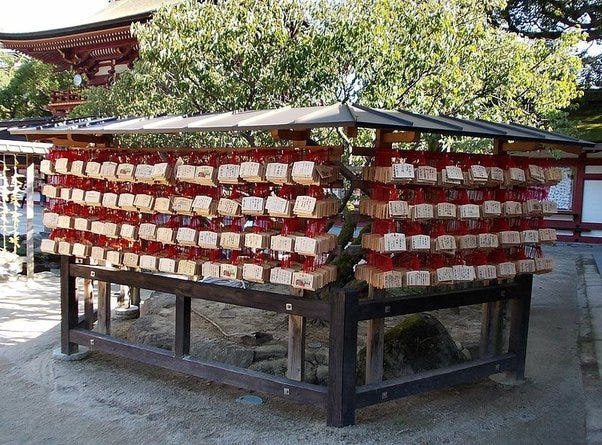

Ema (絵馬 ; picture-horse)

These are small wooden plaques in which Shintō and Buddhist worshippers write prayers or wishes. They are left hanging up at the shrine, where the deities are believed to receive them.

In ancient times people would donate horses to the shrines for good favor; over time this was transferred to a wooden plaque with a picture of a horse, and later still to the various wooden plaques sold today for the same purpose.

→ Ema on display at Dazaifu Tenmangu shrine in Fukuoka Prefecture, Japan [Source: File:Dazaifu Tenmangu 08.jpg]

Setsumatsusha (摂末社)

Sessha (摂社, auxiliary shrine) and massha (末社, undershrine) a.k.a. eda-miya (枝宮, branch shrine) are collectively known as setsumatsusha (摂末社). They are small or miniature shrines entrusted to the care of a larger shrine, generally due to some deep connection with the enshrined deity.

The two terms used to have legally different meanings, but are today synonyms. Setsumatsusha can lie either inside (境内摂末社, keidai setsumatsusha) or outside (境外摂末社, keigai setsumassha) the main shrine's premises.

Being true shrines, setsumatsusha have most features other types of shrines have, including doors and often stairs. However, Misedana-zukuri (見世棚造 or 店棚造, showcase style) is a style normally used only in sessha and massha. It owes its name to the fact that, unlike other shrine styles, it doesn't feature a stairway at its entrance, and the veranda is completely flat.