Temple Architecture Styles : Myanmar Architecture

Myanmar’s architecture style is primarily found in Myanmar, but may be found in or influence neighbouring regions. The prominent examples of Myanmar architecture include the various temples and stūpas found there.

Myanmar’s architecture shows some influence from Nāgara and Sinhala architecture. During colonial period, some European influence could be seen as well.

General terms and features:

Kyaung (ဘုန်းကြီးကျောင်း)

— Buddhist monasteries*, comprising the domestic quarters and workplaces of Buddhist monks. Some Myanmar Kyaungs are sometimes also occupied by sāmaṇēra (novice monks) , kappiya (lay attendants) , thilashin (nuns) , and white-robed phothudaw (ဖိုးသူတော် ; acolytes). Kyaung has traditionally been the centre of village life in Burma, serving as both the educational institution for children and a community centre, especially for merit-making activities such as construction of buildings, offering of food to monks and celebration of Buddhist festivals, and observance of upōsatha. Monasteries are not established by members of the saṅgha, but by laypersons who donate land or money to support the establishment.

*The term Kyaung is also used to describe Christian churches, Sanatanist temples, and Chinese folk religion temples.Phaya (ဘုရား) — an umbrella term for pagodas, images of Buddha, as well as royal and religious personages, including Buddha, kings, and monks

Pahto (ပုထိုး)

— hollow square or rectangular buildings built to resemble caves, with chambers that house images of Buddha\

Zedi (စေတီ)

— derives from Pali cetiya (shrine hall enshrining stūpa; Caitya) but refers to both stūpas & caityas i.e. pagodas. There are main 4 types of Myanmar zedis

:

Datu zedi (ဓာတုစေတီ, from Pali dhātucetiya) or datdaw zedi (ဓာတ်တော်စေတီ) - zedis enshrining relics of Buddha or arhats

Paribawga zedi (ပရိဘောဂစေတီ, from Pali paribhogacetiya) - zedis enshrining garments and other items (alms bowls, robes, etc.) that belonged to the Buddha or sacred personages

Dhamma zedi (ဓမ္မစေတီ, from Pali dhammacetiya) - zedis enshrining sacred texts and manuscripts, along with jewels and precious metals

Odeiktha zedi (ဥဒ္ဒိဿစေတီ, from Pali uddissacetiya) - zedis built from motives of piety, containing statues of the Buddha, models of sacred images

General parts of temples, pagodas and kyaungs:

Hti (ထီး)

— finial ornament resembling an umbrella that tops almost all Myanmar pagodas. Hti have been found on pagodas constructed by all four of the pagoda building ethnic groups of Myanmar: the Mon, the Bamar (Burmans), the Rakhine (Arakanese) and the Shan.

Seinhpudaw (စိန်ဖူးတော် ; esteemed diamond bud) : tip of hti, studded with precious stones.

Pyatthat (ပြာသာဒ်)

— multi-staged roof, with an odd number of tiers (3–7) incorporated into Myanmar Buddhist and royal architecture

General characteristics of temple complexes:

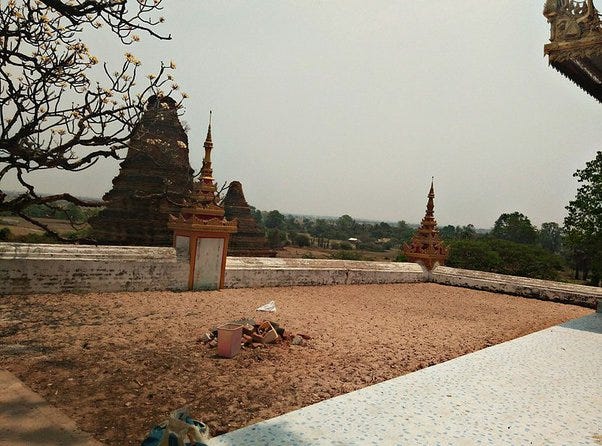

A temple complex can have a central temple or central zedi along with one or more subsidiary structures including smaller zedis, true stūpas, worship halls, subsidiary temples and pavilions. This structures can be surrounded by one or more enclosures, having gates usually in cardinal directions.

A few complexes consist of paired main structures : paired temples, paired zedis, or a temple & a zedi. Less common complexes like Paya-thon-zu consist of triplets of main structures

General characteristics of monasterial complexes:

The typical kyaung consists of a number of buildings called kyaung zaung (ကျောင်းဆောင်):

Zedi (pagoda, as described above)

Shrines to the arhats Sīvali and Shin Upagutta

Tagundaing (တံခွန်တိုင်)

— ornamented flagstaff celebrating the submission of local nats (animistic spirits) to the Dhamma

Cooking quarters

Living quarters for the monks and the sayadaw (senior monks and abbots)

Various pavilions and halls including following:

Gandhakuti (ဂန္ဓကုဋိ, from Pali gandhakūṭi) — pavilion that houses the monastery's principal image of the Buddha

{Traditional Konbaung era monasteries had Buddha images in Pyatthat hsaung [See below]}Dhammayon (ဓမ္မာရုံ) — assembly hall used for sermons and communal purposes

Thein (သိမ်, from Pali sīmā) — ordination hall as prescribed by the Vinaya

Kyetthayei khan (ကျက်သရေခန်း) — storage room

Zayat (ဇရပ်)

— open-air pavilions used as rest houses.

Zayats are not unique to kyaungs or to Buddhism, but can be found as standalone structures or as part of non-Buddhist religious complexes.Traditional monasteries of Konbaung era consisted of the following halls:

Pyatthat hsaung (ပြာသာဒ်ဆောင်) — main chapel hall that housed images of the Buddha

Hsaungmagyi (ဆောင်မကြီး) or hsaungma (ဆောင်မ) — main assembly hall for lectures, ceremonies and housing junior monks

Sanu hsaung (စနုဆောင်) — residential hall of the monastery abbot

Bawga hsaung (ဘောဂဆောင်) — storage room for monks' provisions

In pre-colonial times, royal monasteries were organized as complexes known as kyaung taik (ကျောင်းတိုက်), composed of several residential buildings, including the main building, kyaunggyi (ကျောင်းကြီး) or kyaungma (ကျောင်းမ), which was occupied by the residing sayadaw, and smaller structures called kyaungyan (ကျောင်းရံ), which housed the sayadaw's disciples. The complexes were walled compounds, and also housed a library, ordination halls, meeting halls, water reservoirs and wells, and utility buildings.

Development

2nd century BCE – 11th century CE

Pyu Period (2nd century BCE – c. 1050 CE)1

Śrī Kṣetra kingdom (c. 3rd to 9th century CE – c. 1050s CE)

Polities:

The earliest examples of Myanmar temple architecture are dated to Pyu period in Upper Burma. Pyu city-states were founded as part of the southward migration by Tibeto-Burman-speaking Pyu people, the earliest inhabitants of Myanmar of whom records are extant.

Temples:

During Pyu period, cylindrical stupas with 4 archways and often with a hti (umbrella) on top were built. Beikthano, one of the first Pyu centers, contains urbanesque foundations which include a monastery and stūpa-like structures. Pyu stūpas were built from ~200 BCE – 100 CE and were sometimes used for burial. Early stūpas, temples and pagodas are topped with htis and finials or spires symbolizing Theravada Buddhist transcendence.

Pyu period architecture had significant influence on Bagan period architecture: the “one-face” (single main entrance) type Bagan-style zedis developed from 2nd century CE Beikthano temples, while the “four-face” ones developed from 7th century CE Śrī Kṣetra temples (in present-day Pyay).

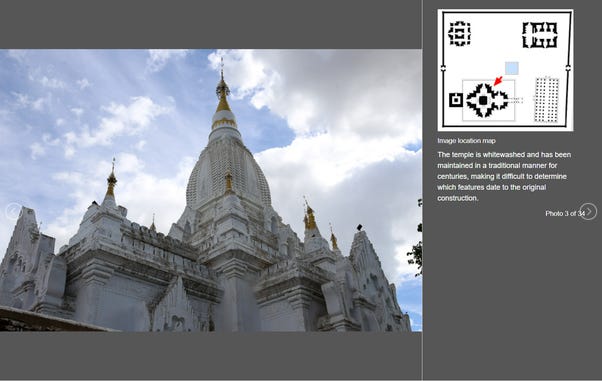

Leimyethna Paya Temple (Temple of four faces) in Pyay may have been one of the Śrī Kṣetra temples. However there is some controversy regarding the age of the monument: although the Buddhist reliefs suggest an early 7th century CE date, the temple may have been built (or rebuilt) in the Bagan era with Pyu-era artifacts reinstalled as objects of worship. This temple also shows vaulting using semi-circular arches, but since the dating is controversial, it cannot be certain if vaulting was already being used in Myanmar at this point in time.

→ Pyu-period pagodas examples:

Conical zedis Payama Stūpa (Built 4th-7th century CE) and Payagi Stūpa (Built 5th-9th century CE) in Sri Ksetra, Hmawza, Myanmar — among the oldest structures of middle Pyu period [Source: Payama Stupa, Pyay, Myanmar AND Payagyi Stupa, Pyay (Prome), Myanmar]

Cylindrical shape Bawbawgyi pagoda in Sri Ksetra, Hmawza, Myanmar (Built 6th-7th century CE) [Source: Bawbawgyi Paya Stupa, Pyay (Prome), Myanmar]

→ Pyu period temples examples:

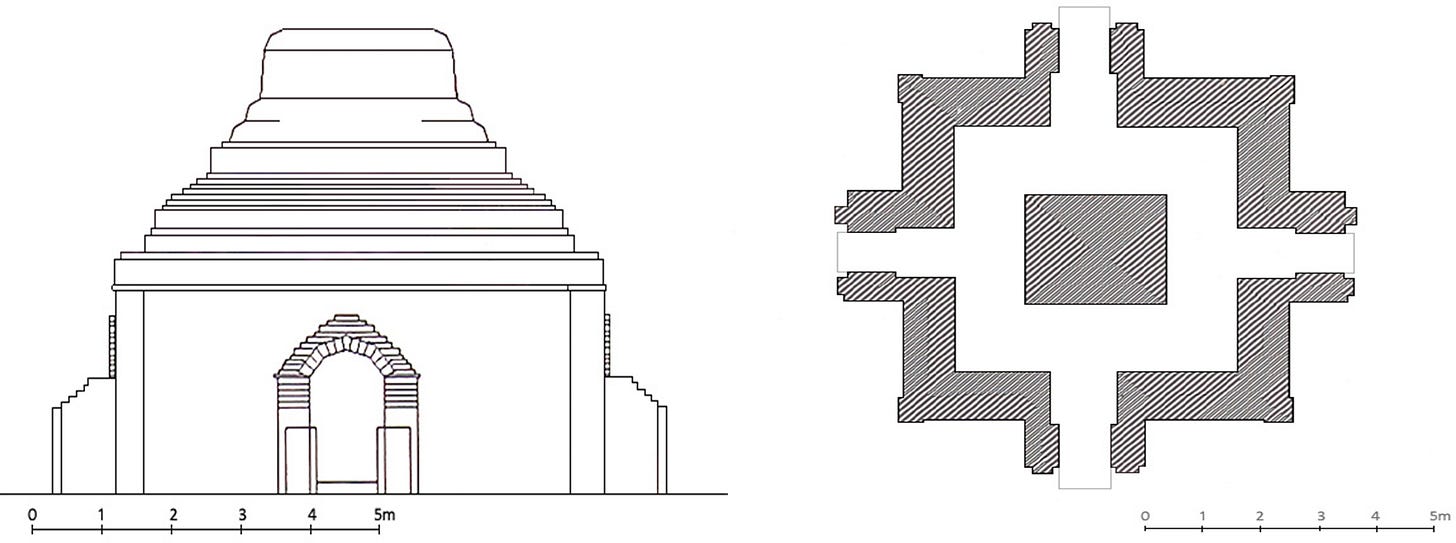

Leimyethna Paya Temple (Temple of four faces) in Pyay, Bago region, Myanmar. The roof of the temple comprises three or four tiers of brickwork rising to a central tower, most of which is no longer present. The tower may have resembled the tapering cylindrical tower still visible at the nearby Bebe Paya. There is some controversy regarding the age of the monument. Although the Buddhist reliefs suggest an early 7th century CE date, the temple may have been built (or rebuilt) in the Bagan era with Pyu-era artifacts reinstalled as objects of worship. This temple also shows vaulting using semi-circular arches, but since the dating is controversial, it cannot be certain if vaulting was already being used in Myanmar at this point in time. (Built possibly 7th century CE) [Source: Leimyethna Paya Temple, Pyay (Prome), Myanmar]

→ Pyu period art examples:

Left: sandstone Stūpa relief [Source: File:Stone bas-relief of stupa.jpg - Wikimedia Commons]

Right: Remains of sandstone Viṣṇu-Lakṣmī relief [Source: File:Statue of Vishnu and Lakshmi.jpg - Wikimedia Commons]

11th century CE – 13th century CE

Bagan Empire (9th century CE – 13th century CE)

Polities:

Bagan Empire grew out of a small 9th century CE settlement at Bagan by Bamars, who entered Ayeyarwady valley from Dàméng/Dàli/Dàfēngmin Kingdom2 (centred in Yunnan, China). Over the next 200 years, the small principality gradually grew to absorb its surrounding regions until 1050s-1060s CE when king Anawrahta founded Bagan Empire, unifying Ayeyarwady valley and its periphery under one polity. By late 12th century CE Anawrahta's successors had extended their influence farther to the south into upper Malay peninsula, to the east at least to Salween river, in the farther north till the current China border, and to the west in northern Arakan and Chin Hills.

In 12th and 13th centuries CE, Bagan, alongside Kambuja Empire, was one of two main empires in mainland Southeast Asia.

The empire went into decline in the mid-13th century CE as the continuous growth of tax-free religious wealth by 1280s CE had severely affected the crown's ability to retain the loyalty of courtiers and military servicemen.

Temples:

Stūpas:

During Bagan period, Pyu-style stūpas were transformed into monuments reminiscent of alms bowls or gourd-shaped domes, unbaked brick, tapered and rising roofs, Buddha niches, polylobed arches and ornamental doorways influenced by India's Pāla Empire. Stucco was widely used in Bagan, especially by Mon people. Stucco features of Bagan structures include garlands, flames or rays of the sun, peacock tail feathers and mythical creatures. Bagan, with >10,000 of Myanmar's red brick stūpas and pagodas, had become a centre of Buddhist architecture by mid-12th century CE.

Most Bagan style stūpas have square base although a few have pentagonal base — the pentagonal design seems to be a hybrid of the “one-face” and “four-face” type zedis that descend from 2nd century CE Beikthano and 7th century CE Sri Kshetra Pyu period temples. Historian Pierre Pichard notes that the term nga-myet-hna (five-sided temple) was used in Bagan era itself and occurs in an inscription dated to 1242 CE.

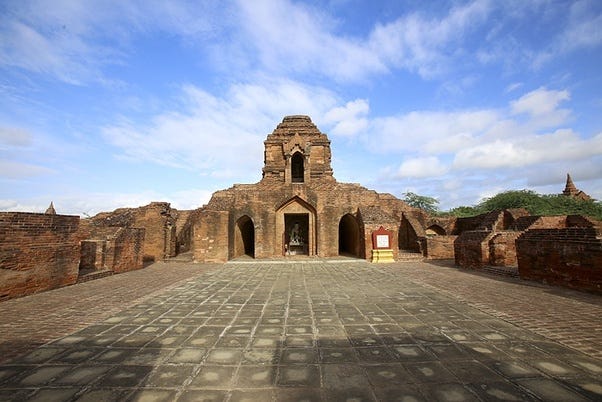

→ Bagan period temples examples:

L2R: East Hpetleik and West Hpetleik in New Bagan — they represent an intermediary step in the transition from Pyu prototypes at Sri Ksetra to the dominant forms at Bagan which emerged in King Anawrahta's reign and later. The essential form of the Hpet-leik monuments is a square-shaped solid core surrounded by an ambulatory, capped with a centrally-placed stupa. This design is consistent with Leimyethna Paya at Sri Ksetra (Pyay) which was probably built in 7th century CE (Built 11th century CE) [Source: orientalarchitecture.com/sid/1195/myanmar/bagan/east-and-west-hpet-leik]

Nathlaung Kyaung Temple in Bagan, Mandalay Region, Myanmar — a Viṣṇu temple built in 10th or 11th century CE, the oldest temple of Bagan period in Bagan archaeological site. It may have been built by Indian artisans brought into Bagan, during 10th century CE, to work on it and other temples. [Source: Nathlaung Kyaung Temple - Wikipedia]

Lawkananda stūpa in New Bagan township enshrines a replica of the sacred Buddha tooth relic which had been sent to Burma from Sri Lanka as a gesture of goodwill between the two countries. (Built 11th century CE under Anawrahta Minsaw (r. 1044–1077 CE)) [Source: Monuments of Bagan: Rise of the First Burmese Empire | Sahapedia]

Ananda Temple in Bagan, Mandalay Region, Myanmar (Built 1090 CE) [Source: File:Ananda-Temple-2.JPG - Wikimedia Commons]

Yahandar Temple in Pyay, Bago Region, Myanmar — a small temple with corbelled arch entrance (Built 13th century CE) [Source: Yahandar-gu Temple, Pyay (Prome), Myanmar]

Paya-thon-zu (Temple of 3 Buddhas) in Bagan, Mandalay Region, Myanmar — the only triple-monument at Bagan with interconnected shrine corridors. (Late 13th century CE) [Source: Paya-thon-zu Temple, Bagan, Myanmar]

Mingalazedi in Bagan, Mandalay Region, Myanmar — last major Bagan monument built before 1287 CE Mongol Invasion (Built 1270s CE) [Source: Mingalazedi Temple, Bagan, Myanmar]

A panorama of Bagan showing the various temples constructed there [Source: Bagan - Wikipedia]

Load-bearing true arches and vaulting:

Load-bearing true arches are also known in Myanmar temples at least since 11th century CE, as evidenced by entrance of Nanpaya Temple in Myinkaba, Mandalay region, Myanmar. While Nanpaya temple was built by the captive king Makuta of Thaton kingdom, true arch seems to have been adopted by Bagan kings nonetheless, as seen with Dhammayazika Pagoda of Bagan.

Vaulting is also known in Bagan period since 11th century CE as a consequence of knowledge of true arches — the vaulting techniques of the Bagan era were lost in the later periods but true semicircular arches could be seen in Mrauk U kingdom’s temples of 15th-16th century CE indicating that Mrauk U retained or independently adopted true arches after their use declined in Bagan Empire’s territories. True semicircular arches also continued to be in present, but mostly as gateways and without any load over them.

→ Bagan period vaulted temples examples:

Nanpaya Temple, a Sanatanist temple dedicated to Brahmā. It was built by Mon king Makuta, the last king of Thaton kingdom, in 1067 CE after getting captured by Bagan Empire. [Source: File:Nanpaya-Bagan-Myanmar-01-gje.jpg - Wikimedia Commons]

Dhammayazika Pagoda in Bagan (Built 12th century CE) [Source: Bagan - Wikipedia]

13th century CE – 18th century CE

Shan States (1215 CE – 1885 CE)

Kingdom of Mrauk U (September 1430 CE – 1785 CE)

Toungoo Empire (1510 CE – 1752 CE)

Polities:

After the decline of Bagan empire, a number of small kingdoms came into existence including : pre-British Shan States (1215 CE – 1885 CE), Hanthawaddy Kingdom (1287 CE – 1552 CE), Myinsaing Kingdom (1297 CE – 1313 CE), Pinya Kingdom (1313 CE – 1365 CE), Sagaing Kingdom (1315 CE – 1365 CE), Ava Kingdom (1365 CE – 1555 CE), Prome Kingdom (1482 CE – 1542 CE) etc. The establishment of Shan states was a part of the large scale Tai migration that led to establishment of Ahom kingdom in India in 1229 CE and Sukhothai kingdom in Thailand in 1253 CE.

First Toungoo Empire (1510 CE – 1599 CE) and Second Toungoo Empire (1599 CE – 1752 CE) succeeded in uniting most of present-day Myanmar. Under Toungoo rule, the monarch’s powers were significantly larger than those of subordinate rulers, a system that continued with Konbaung period. Second Taungoo Empire fell due to the Mon rebellion that established Second Hanthawaddy Kingdom (1740 CE – 1757 CE) itself disestablished by Konbaung kingdom.

Mrauk U Kingdom, with its capital at Mrauk U, started as and remained a protectorate of Bengal Sultanate during 1429–1531 CE but went on to conquer Chittagong with the help of the Portuguese mercenaries. It remained independent until 1785 CE when it was conquered by Konbaung Empire.

In 1608 CE the Portuguese mercenary Filipe de Brito e Nicote, known as Nga Zinka to the Burmese, plundered Shwedagon Pagoda. His men took the 300-ton Great Bell of Dhammazedi, donated in 1485 CE by Mon king Dhammazedi. De Brito's intention was to melt the bell down to make cannons, but it fell into Bago River when he was carrying it across. To this date, it has not been recovered.

Temples:

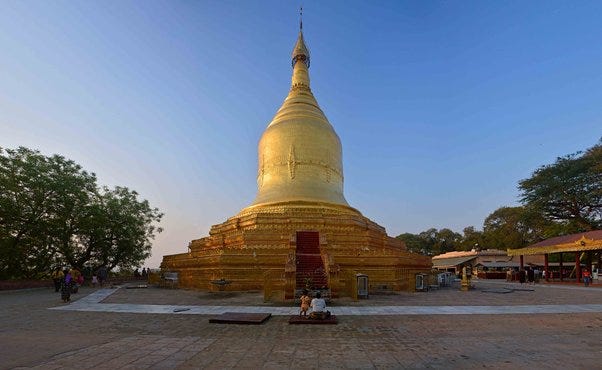

Sri Lankan influence could be seen over Myanmar architecture stūpas at least since Toungoo empire, as seen in 17th century CE hemispherical Kaunghmudaw Pagoda based on Ruwanwelisaya of Sri Lanka.

→ Toungoo Empire built temples examples:

Kaunghmudaw Pagoda in Sagaing — mostly Sri Lankan style stūpa with Myanmar influence (Built 1636–1648 CE under king Thalun) [Source: Kaunghmudaw Pagoda, Sagaing]

Mrauk U Temples usually have single entrance and are somewhat fortified. Some of the early temples did have multiple entrances, for example Le-myet-hna Temple (Four-Sided Temple) built under Mrauk U kingdom founder Narameikhla had 4 entrances on the cardinal directions.

→ Mrauk-U kingdom temples examples:

Le-myet-hna Temple (Four-Sided Temple) in Mrauk U, Rakhine State, Myanmar — has 4 entrances, one to each cardinal point, and 4 seated Buddhas round a central column. (Built 1430 CE under Narameikhla) [Source: File:Le Myet Hna Temple - Mrauk U.jpg - Wikimedia Commons]

Shite-thaung Temple in Mrauk U, Mrauk U District, Rakhine State, Myanmar (Built 1535 CE) [Source: Shite-thaung Temple - Wikipedia]

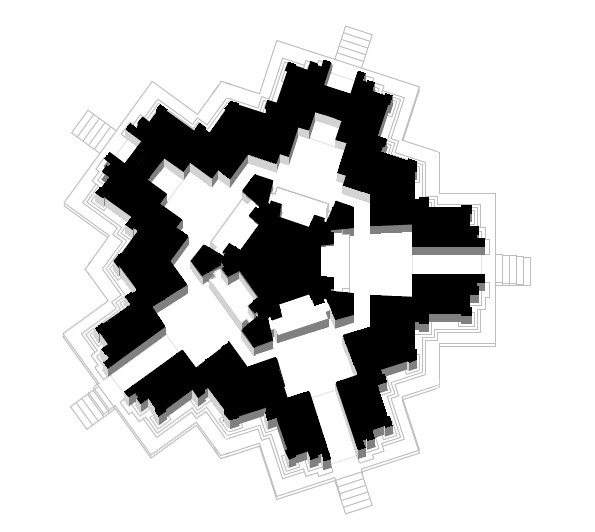

Koe-thaung Temple Complex in Mrauk U, Mrauk U District, Rakhine State, Myanmar — the load bearing semi-circular arches inside indicate that Mrauk U retained or independently adopted arches after their use declined in Bagan Empire’s territories. (Built 1554–1556 CE under king Dikkha) [Source: Koe-thaung Temple - Myanmar Tours]

Htuk-Kan-Thein in Mrauk U, Mrauk U District, Rakhine State, Myanmar — an ordination hall (thein) built like a fort, the main pagoda is located towards the back of the temple. While the outer portion has multiple entrances reached via stairs, the inner portion itself has only one. (Built 1571 CE) [Source: File:HtukKanThein.jpg - Wikimedia Commons]

18th century CE – 20th century CE

Konbaung Empire (1752 CE – 1885 CE)

British Burma (1824 CE – 1948 CE)

Polities:

Konbaung empire was the last independent Burmese kingdom before the colonial expansion of British into Myanmar. Konbaung waged wars against Qīng and Arakanese, as well as disestablished the Second Hanthawaddy Kingdom, vassalized the Manipur kingdom and significantly weakened Ahom kingdom leading to its gradual fall to British.

Konbaung empire was destroyed during Anglo-Burmese wars, which also saw the establishment of Manipur kingdom and the Federated Shan States as vassal states of the British. After the Anglo-Burmese wars, British Empire established its control over Myanmar. In 1826 CE, Burma lost Arakan, Manipur, Assam and Tenasserim to the British in First Anglo-Burmese War. In 1852 CE, the British easily seized Lower Burma in Second Anglo-Burmese War. King Mindon Min tried to modernise the kingdom and in 1875 CE narrowly avoided annexation by ceding the Karenni States. The British, alarmed by the consolidation of French Indochina, annexed the remainder of the nation in Third Anglo-Burmese War in 1885 CE.

Temples:

The most significant religious construction during Konbaung dynasty occurred during the reign of the 3rd king Hsinbyushin. Hsinbyushin reconstructed Shwedagon Pagoda to its current height of 99m — the structure is located on Singuttara Hill, Yangon, Myanmar. Shwedagon Pagoda combines the various forms Myanmar stūpas into a single structure, and spurred the construction of a few replicas as well.

Traditional monasteries of Konbaung era consisted of the following halls:

Pyatthat hsaung (ပြာသာဒ်ဆောင်) — main chapel hall that housed images of the Buddha

Hsaungmagyi (ဆောင်မကြီး) or hsaungma (ဆောင်မ) — main assembly hall for lectures, ceremonies and housing junior monks

Sanu hsaung (စနုဆောင်) — residential hall of the monastery abbot

Bawga hsaung (ဘောဂဆောင်) — storage room for monks' provisions

→ Konbaung Empire built temples & pagodas examples:

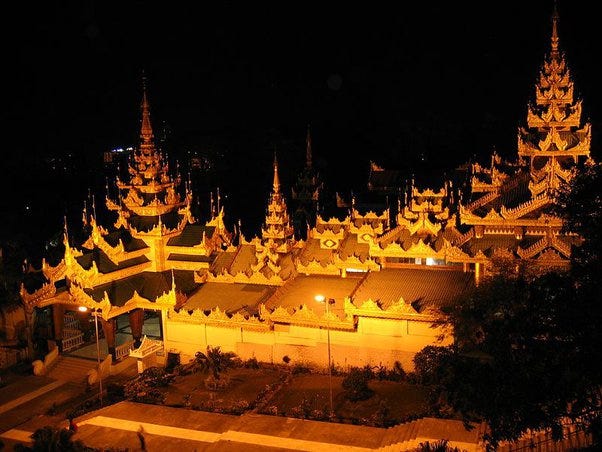

Shwedagon Pagoda on Singuttara Hill, Yangon, Myanmar (reconstructed under Konbaung dynasty 1775 CE) [Source: File:Shwedagon Pagoda 2017.jpg]

Mahamuni Buddha Temple Complex in Mandalay, Mandalay Region, Myanmar (Built 1785 CE, Rebuilt after 1884 CE fire) [Source: Maqhamuni Paya, Mandalay, Myanmar. Editorial Stock Image - Image of kuthodaw, landmark: 30095584]

Maha Aungmye Bonzan Monastery in Inwa, Mandalay Region, Myanmar — the lower section has triangular entrance cells with Candraśālā arch façade, while upper section immediately above has trefoil arched blind gateways also having Candraśālā arch façade. (Built 1818 CE under queen Nanmadaw Me Nu, restored 1873 CE after earthquake damage) [Source: File:Inwa (Ava), Mandalay 39.jpg - Wikimedia Commons]

→ Other Myanmar architecture religious structures of 18th-20th century CE:

Mahā Sāsanā Raṃsī (Burmese Buddhist Temple) in Singapore (Established 1875 CE, moved to present location 1988 CE) [Source: Burmese Buddhist Temple - မဟာသာသနရံသီ မြန်မာကျောင်း]

British Colonial period saw little to no new temples being constructed, with the British forces sometimes plundering Myanmar temples, especially Shwedagon Pagoda. Conversely, a few structures like Myadaung Monastery were put under conservation.

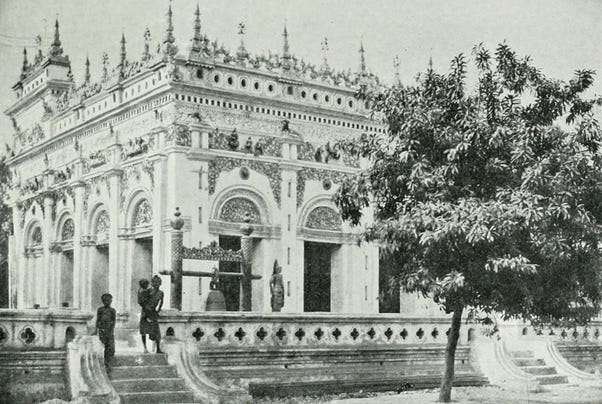

European influence over Myanmar structures could be seen during this period driven by both increasing British influence in Myanmar and Myanmar nobility & aristocracy travelling to Europe.

→ European influenced Myanmar religious structures of Konbaung and British periods:

Yaw Mingyi Monastery in Mandalay, Mandalay Region, Burma — modelled after a southern Italian hotel seen by the monastery’s patron Pho Hlaing, posthumously called Yaw Mingyi. (Built 1866 CE)[Source: File:Yaw Mingyi Monastery.PNG - Wikimedia Commons]

20th century CE – present

Independent Myanmar (1948 CE – present)

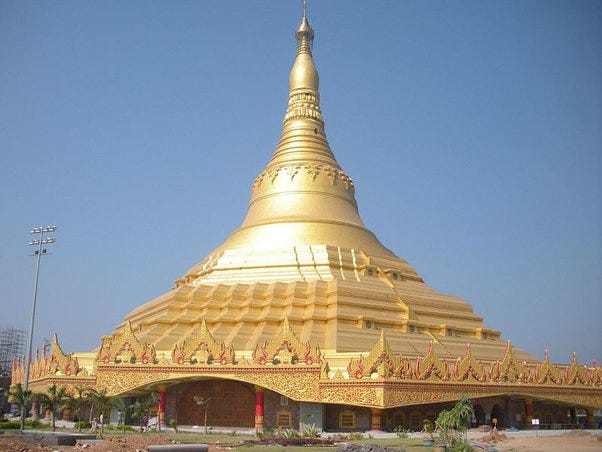

Myanmar became independent in 1948. Since then, new Myanmar architecture temples have been built in Myanmar and other nations, mostly in South Asia and South-East Asia.

Shwedagon Pagoda notably serves as model for many new pagodas.

→ Post-1948 Temples and Temple Complexes examples:

Mahā Atulaveyan Kyaungdawgyi in Mandalay, Mandalay Region, Myanmar. The original monastery structure was built in 1857 CE under king Mindon, using teak, covered with stucco on the outside, with its peculiar feature being that it was surmounted by 5 graduated rectangular terraces instead of the traditional pyatthat tiered and spired roofs. The structure burned down in 1890 CE after a fire in the city destroyed both the monastery and the 9.1m tall Buddha image, as well as complete sets of the Tipitaka. In 1996 CE, Myanmar’s Archaeological Department reconstructed the monastery with prison labor. [Source: File:20160729 Atumashi Mandalay 5865.jpg - Wikimedia Commons]

Kongmu Kham Complex in Namsai, Namsai District of Arunachal Pradesh, India (Built 2008–2010) [Source: File:Golden Pagoda Namsai.jpg - Wikimedia Commons]

→ Post-1948 Zedis examples:

Maha Wizaya Pagoda in Yangon, Myanmar — an 8-sided pagoda built to commemorate unification of Myanmar Buddhist sects (Built 1980) [Source: Maha Wizaya Pagoda, Yangon, Myanmar]

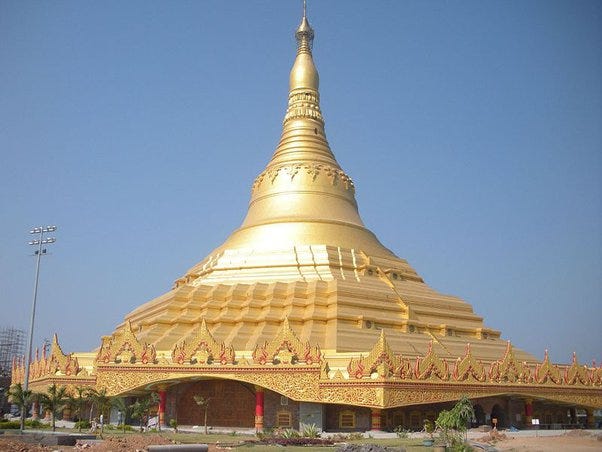

Global Vipassana Pagoda in Gorai, North-west of Mumbai, Maharashtra, India — Based on Shwedagon Pagoda (Built 2000–2008) [Source: File:GlobalVipasanaPagoda.JPG - Wikimedia Commons]

Uppatasanti Pagoda in Naypyidaw, Naypyidaw Union Territory, Myanmar — Based on Shwedagon Pagoda (Built 2006–2009) [Source: File:Uppatasanti Pagoda-02.jpg]

Shwedagon Pagoda replica in Lumbini Natural Park in Desa Dolat Rayat, Berastagi in North Sumatra, Indonesia [Source: File:Shwedagon Pagoda Steel.jpg]

Structural Details

Decorative Elements

Various types of decorative elements can be found on Myanmar temples, zedis and monasteries.

Reliefs

Kīrtimukha

Myanmar-style Kīrtimukha reliefs are markedly different from the general Indian and Indonesian Kīrtimukha reliefs — the reliefs have complete face and two arms while the general Indian and Indonesian Kīrtimukha reliefs consist of only the upper jaw and less frequently the lower jaw, and hardly ever have arms.

→ Kīrtimukha reliefs examples:

Eindawya Pagoda, Mandalay, Myanmar [Source: Eindawya Pagoda (အိမ်တော်ရာဘုရား), Mandalay, Myanmar]'

Manok-Thi-Ha

Manok-Thi-Ha is a double bodied lion with a single human head. Often, the being is enclosed in a lintel arch.

This relief is common on corners of walls, with one lion body on each of the meeting walls and the human head on their meeting point. It can also be found on walls and roofs

→ Manok-Thi-Ha examples:

Manok-Thi-Ha on walls of pyathat-hsaung of Maha Aung Mye Bonzan Monastery in Inwa, Mandalay Region, Myanmar [Source: Maha Aung Mye Bonzan Monastery, Inwa (Ava), Myanmar]

Manok-Thi-Ha on corners of walls, enclosed in a corner lintel arch, at pyathat-hsaung of Maha Aung Mye Bonzan Monastery

Manok-Thi-Ha on corners of walls, enclosed in a corner lintel arch, at pyathat-hsaung of Maha Aung Mye Bonzan Monastery

Manok-Thi-Ha on centre point of a roof, enclosed in a lintel arch, at pyathat-hsaung of Maha Aung Mye Bonzan Monastery

Other reliefs

→ Other Myanmar religious reliefs examples:

Closer view of door of Nat Taung Kyaung Monastery in Bagan, Mandalay Region, Myanmar. The door leaves depict 2 dēvas supporting lotus leaf sprigs. On either side of the dēva pair are 2 kinnara with long tail feathers upon which rest various small birds. The doors that were formerly here were somewhat simpler in design, but used the same motif.

[Source: Nat Taung Kyaung Monastery, Bagan, Myanmar]

Tagundaing (တံခွန်တိုင်)

Tagundaing is an ornamented victory pillar or flagstaff, typically 18–24m high, found within the grounds of Myanmar Buddhist pagodas and kyaungs (monasteries). These ornamented columns were raised within religious compounds to celebrate the submission of nats (local animistic spirits) to Dhamma.

The pillar’s base usually features the earth deity (Vasudharā) or Thagyamin (highest-ranking nat in traditional Myanmar Buddhist belief) or both, while the top may feature the mythical bird Haṁsa (usually a swan or goose), Kinnara (bird human) or other animals or mythical beings.

→ Tagundaing examples:

Kyaik Pun Paya’s Tagundaing featuring a Haṁsa on top. The pillar has octagonal bas, and is tapering cylinder [Source: File:Kyaik Pun Paya - Bago, Myanmar 20130219-13.jpg]

Tagundaing in an “enclosure”, and having tapering square shape [Source: File:Inle Lake (16158076445).jpg]

Shwemawdaw Paya Complex’s Tagundaing having square base and non-tapering cuboid shape, featuring a small Haṁsa atop another larger Haṁsa [Source: File:Shwemawdaw Paya - Bago, Myanmar 20130219-20.jpg]

Tagundaing at Hpaung Daw U Pagoda Complex modelled after Aśōka Pillars [Source: File:Inle Lake - Phaung Daw U Paya, Myanmar (169496788).jpg]

Roofing and Roof structures

Pyatthat (ပြာသာဒ်)

These are multi-staged roof, with an odd number of tiers (3–7) incorporated into Myanmar Buddhist and royal architecture. These roofs may be built of wood or bricks.

→ Pyatthat roofs examples:

Multiple Pyatthat roofs visible on Wat Srichum in Lampang, Thailand. The hti finials are visible placed placed on all of the Pyatthat roofs (Built 13th century CE) [Source: File:Burmese-style Wat Srichum, Lampang.jpg]

Multiple Pyatthat roofs in Shwedagon Pagoda Complex [Source: File:ShwedagonIMG 7608.JPG]

Brick-built Pyatthat at Pyathat-hsaung of Maha Aung Mye Bonzan Monastery in Inwa, Mandalay Region, Myanmar [Source: https://orientalarchitecture.com/sid/1160/myanmar/inwa/maha-aung-mye-bonzan-monastery]

Arches and vaults

Arches and vaults of Myanmar temples and zedis are usually semi-circular or pointed.

Load bearing true arches and vaults are largely limited to temples built under Bagan Empire and Mrauk U Kingdom. True arches have been retained in present time, but usually serve as gateways or blind gateways (purely decorative arches leading to nowhere).

Arches can also be used as part of decorative motifs, decorative niches and facades. Multi-foil arches are usually limited to creating niches on insides and outsides of the temples and zedis.

A few examples of corbelled arches (i.e. false arches) also exist, but are relatively less common than true arches or architraves.

→ Myanmar temple load bearing semicircular arches examples:

Arched entrance of Nanpaya Temple in Myinkaba (a village south of Bagan), Mandalay Region, Myanmar (Built by Mon king Makuta, the last king of Thaton kingdom, in 1067 CE). [Source: File:Nanpaya-Bagan-Myanmar-01-gje.jpg - Wikimedia Commons]

Triple arched entrances to a section of Ananda Temple Complex in Bagan, Mandalay Region, Myanmar [Sources: Ananda Pahto Temple, Bagan, Myanmar]

Semicircular arches inside Abeyadana Temple in Bagan, Mandalay Region, Myanmar [Source: Abe-ya-dana-hpaya Temple, Bagan, Myanmar]

→ Myanmar temple load bearing pointed arches examples:

Pointed arched entrance to East Hpet-leik Complex in Bagan, Mandalay Region, Myanmar [Source: East and West Hpet-leik, Bagan, Myanmar]

Pointed arch vaults forming the external entrances of Abeyadana Temple in Bagan, Mandalay Region, Myanmar [Source: Abe-ya-dana-hpaya Temple, Bagan, Myanmar]

Pointed arched entrance to Dhammayangyi Temple in Bagan, Mandalay Region, Myanmar — the niches at the base once had door keeper statues. [Source: Dhammayangyi Temple, Bagan, Myanmar]

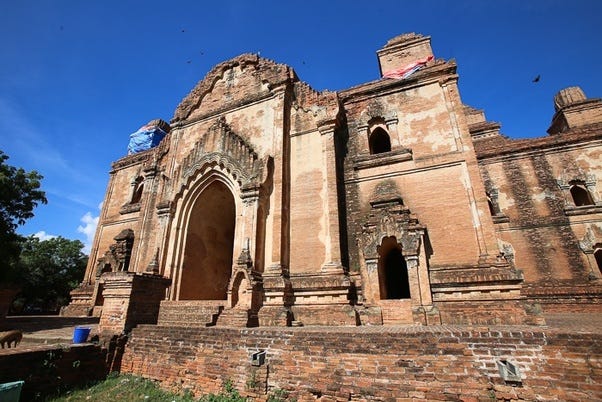

Pointed arched entrances of Gawdawpalin Temple in Bagan, Mandalay Region, Myanmar [Source: Gawdawpalin Temple, Bagan, Myanmar]

Load bearing pointed arched inside Ananda Temple in Bagan, Mandalay Region, Myanmar [Sources: Ananda Pahto Temple, Bagan, Myanmar]

Pointed arch vaults inside Dhammayangyi Temple in Bagan, Mandalay Region, Myanmar [Source: Dhammayangyi Temple, Bagan, Myanmar]

→ Myanmar temples arched windows examples:

Semicircular Arched windows of Abeyadana Temple in Bagan, Mandalay Region, Myanmar [Source: Abe-ya-dana-hpaya Temple, Bagan, Myanmar]

→ Myanmar temples arched niches examples:

Arched niches inside Abeyadana Temple in Bagan, Mandalay Region, Myanmar [Source: Abe-ya-dana-hpaya Temple, Bagan, Myanmar]

→ Myanmar temples decorative arches examples:

Decorative arches over windows of Abeyadana Temple in Bagan, Mandalay Region, Myanmar [Source: Abe-ya-dana-hpaya Temple, Bagan, Myanmar]

A few examples of corbelled arches also exist, but are relatively less common than true arches or architraves.

→ Myanmar temples corbelled arches examples:

Yahandar Temple in Pyay, Bago Region, Myanmar — a small temple with corbelled arch entrance (Built 13th century CE) [Source: Yahandar-gu Temple, Pyay (Prome), Myanmar]

Gateways

Gateways to temple complexes range from simple arches or architraves (Tōraṇa-like structures) to elaborate gateways with pyatthat.

The gateways may feature chinthe (lion-like mythological beings) statues or gatekeeper statues on either sides.

→ Simple Arched Gateways examples:

Gate of KyaiktiYoe Pagoda in Kyaikto, Mon state, Myanmar — an arched gateway with no Pyatthat roofs [Source: File:KyaikHtiYoe Pagoda.jpg]

→ Elaborate Arched Gateways examples:

Gateway of Naga-yon-hpaya Temple in Bagan, Myanmar — features a decorative multi-foil arch over a load bearing true arch leading into an architrave (11th Century CE) [Source: Naga-yon-hpaya Temple, Bagan, Myanmar]

→ Pyatthat gateways examples:

Southern gateway of Bupaya Temple Complex in Bagan, Mandalay Region, Myanmar [Source: Bu-hpaya Temple, Bagan, Myanmar]

Northern gateway of Mahazedi Paya Pagoda Complex in Bago, Mandalay Region, Myanmar [Source: Mahazedi Paya Pagoda, Bago, Myanmar]

Western gate of Shwedagon Pagoda complex with its own Pyatthat roofs [Source: File:Northern gate to Shvedagon pagoda.jpg]

Zedis

Zedis by era-specific style

Pyu style zedis

Conical shaped zedi has already been mentioned previously.

Conical: Payama Stūpa (Built 4th-7th century CE) and Payagi Stūpa (Built 5th-9th century CE) in Sri Ksetra, Hmawza, Myanmar — among the oldest structures of middle Pyu period [Source: Payama Stupa, Pyay, Myanmar AND Payagyi Stupa, Pyay (Prome), Myanmar]

Cylindrical: Bawbawgyi pagoda in Sri Ksetra, Hmawza, Myanmar [Source: File:20160810 Bawbawgyi Pogoda Sri Ksetra Pyay Myanmar 9252.jpg]

Stepped zedi with bell-like upper part: Hanlin archaeological site, Shwebo District, Sagaing Region, Myanmar[Source: File:HanLin.jpg - Wikimedia Commons]

Bagan style zedis

Gourd-shaped: Buphaya Pagoda in Buphaya Pagoda Complex, Bagan, Mandalay Region, Myanmar [Source: Buddhist Stupas of Southeast Asia 101]

Elongated banana bud: Shwezigon Pagoda in Bagan, Mandalay Region, Myanmar (built 11th century CE) [Source: Buddhist Stupas of Southeast Asia 101]

Bell shaped: Dhammayazika Pagoda in Pwasaw village, near Bagan, Mandalay Region, Myanmar [Source: Buddhist Stupas of Southeast Asia 101]

Mrauk U style zedis

Bell-shaped zedi: Ratana-Pon (pile of treasures) Pagoda in Mrauk U, Rakhine State, Myanmar — bell shaped pagoda without ornamentations, reaching 61m in height (Built 1612 CE under king Min Khamaung and queen Shin Htway) [Source: Ratana-Pon Pagoda]

Octagonal Pyramid zedi: Laungbanpyauk Pagoda in Mrauk U, Rakhine State, Myanmar — reaching 37m in height (Built 1525 CE under king Minkhaung [Source: Laungbanpyauk Pagoda]

Shwedagon Pagoda style zedis

A few replicas of Shwedagon pagoda have been built, usually dating to during & after 20th century CE.

→ Shwedagon Pagoda style zedis examples:

Uppatasanti Pagoda in Naypyidaw, Naypyidaw Union Territory, Myanmar [Source: File:Uppatasanti Pagoda-02.jpg]

Replica in Lumbini Natural Park in Desa Dolat Rayat, Berastagi in North Sumatra, Indonesia [Source: File:Shwedagon Pagoda Steel.jpg]

Global Vipassana Pagoda meditation hall in Gorai, North-west of Mumbai, Maharashtra, India [Source: File:GlobalVipasanaPagoda.JPG - Wikimedia Commons]

Other zedi styles

→ Other style zedis examples:

Nga-kywe-na-daung in Bagan, Mandalay Region Myanmar — a brick masonry stūpa from either Pyu period or Bagan period (Dated between 9th-11th century CE) [Source: Nga-kywe-na-daung Stupa, Bagan, Myanmar]

Po-daw-mu-hpaya Stupa in Bagan, Mandalay region, Myanmar — octagonal base, hemispherical mid-section and pyramid spire (Built 11th century CE) [Source: Po-daw-mu-hpaya Stupa, Bagan, Myanmar]

Hsinbyume pagoda in Mandalay, Mandalay Region, Myanmar — built to represent Mount Mērū (Built 1816 CE by then prince Bagyidaw dedicated to his first wife, Hsinbyume (White Elephant)) [Source: Hsinbyume pagoda]

Hpaung Daw U Pagoda on shore of Inle Lake, Shan Hills, Shan State, Myanmar — bell-shaped pagoda over multi-storey temple-like base more elaborate than the usual pagoda bases [Source: Hpaung Daw U Pagoda, Inle Lake]

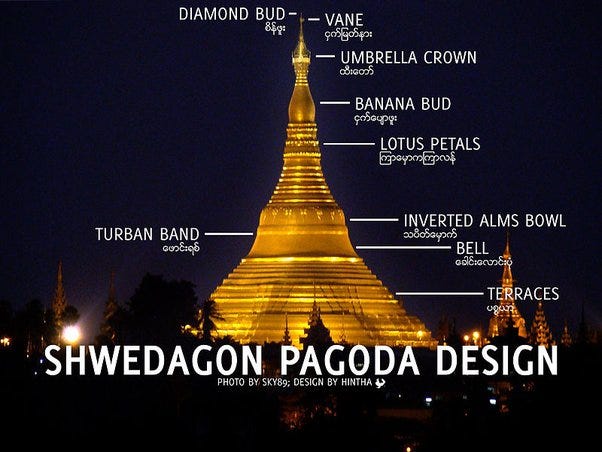

Parts of Zedis

→ Shwedagon Pagoda — labelled diagram showing the various stūpa forms that can be found in Myanmar. Shwedagon Pagoda combines most of them. [Source: File:Shwedagon-Pagoda-anatomy.jpg - Wikimedia Commons]

Hti (ထီး ; umbrella)

Hti forms the finial of all Myanmar pagodas. The tip of the umbrella, which is studded with precious stones, is called seinhpudaw (စိန်ဖူးတော် ; esteemed diamond bud). The umbrella is placed on the top of a pagoda and hung with a multitude of bells. The umbrella of prominent pagodas are often made entirely of gold or silver; in case of temples at Bagan and Mrauk U, the umbrellas are made of stone.

A special ceremony being held for the placing of hti on the pagoda is called hti tin pwe (ထီးတင်ပွဲ).

Hti have been found on pagodas constructed by all 4 of the pagoda building ethnic groups of Myanmar: Mon, Bamar, Rakhine (Arakanese) and Shan.

→ Close up of Shwedagon Pagoda’s umbrella finial [Source: File:Head of Shwedagon Pagoda.JPG]

Pavilions

Pavilions are part of pagoda complexes, temple complexes and kyaung complexes. While some pavilions are limited to kyaung complexes, many are common with rest of the religious complexes.

Pavilions of higher importance may feature pyatthats.

→ Pyatthat roof pavilions examples:

Pavilions of Shwemawdaw Pagoda Complex in Bago, Mandalay Region, Myanmar — one pavilion of each direction shown with a compass rose to indicate directions [Source: Shwemawdaw Pagoda, Bago, Myanmar, compass rose from Cardinal direction - Wikipedia]

Zayat (ဇရပ်)

Zayat serves primarily as a shelter for travellers, at the same time, is also an assembly place for religious occasions as well as meeting for the villagers to discuss the needs and plans of the village. Donors mostly build Zayats along main roads aiming to provide the exhausted travellers with water and shelter.

Theravada Buddhist monks use zayats as their dwelling place while they are exercising precepts on Uposatha days. Buddhist monasteries may have one or more zayats nearby.

Beginning with Adoniram Judson's construction of one in 1818 CE Christian missionaries have also adopted their use.

→ Zayat examples:

Zayat at Kuthodaw Pagoda Complex in Mandalay, Burma [Source: File:Zayat at Kuthodaw Pagoda.jpg - Wikimedia Commons]

Thein (သိမ်) and Sim (သိမ်ႇ)

Thein (သိမ်, from Pali sīmā) are ordination hall as prescribed by the Vinaya. Sim (သိမ်ႇ) are Shan ordination halls and are exclusively used for events limited to the monkhood. Thein is a common feature of Myanmar monasteries (kyaung), although the it may be not necessarily be located on the monastery compound itself.

Architecture of Theins and Thein complexes varies according to the ethnic group involved in their construction: Mrauk U’s ordination halls in particular are built like fortresses, similar to the temples at the site.

The extent of sanctified space in the area housing the thein is marked by boundary stones called nimatta.

→ Parts of Kalyani Ordination Hall Complex in Bago, Bago Region, Myanmar [Source: Kalyani Ordination Hall, Bago, Myannar]

General view of the complex

View north toward the covered walkway. A modern nimatta (boundary stone) stands at center, marking the extent of sanctified space.

Bell tower at one corner of the site.

Central Buddha image inside

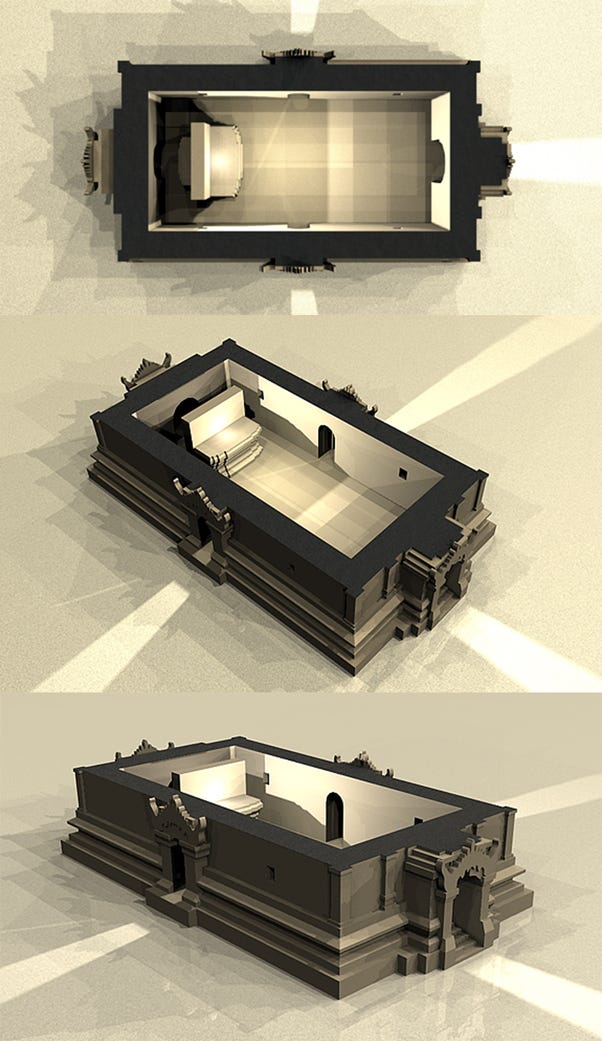

→ Cutaway view of Upāli Ordination Hall between Bagan and Nyaung U, Mandalay Region, Myanmar — Buddha images omitted for simplicity (Built 1200s CE, altered 18th-19th century CE) [Source: Upali Thein Ordination Hall, Bagan, Myanmar]

→ Myanmar Architecture Ordination Halls examples:

Upāli Ordination Hall between Bagan and Nyaung U, Mandalay Region, Myanmar (Built 1200s CE, altered 18th-19th century CE) [Source: Upali Thein Ordination Hall, Bagan, Myanmar]

Htuk-Kan-Thein in Mrauk U, Mrauk U District, Rakhine State, Myanmar — an ordination hall (thein) built like a fort, the main pagoda is located towards the back of the temple. While the outer portion has multiple entrances reached via stairs, the inner portion itself has only one. (Built 1571 CE) [Source: File:HtukKanThein.jpg - Wikimedia Commons and File:Mrauk U, Dukkanthein (6211919307).jpg - Wikimedia Commons]

Andaw Thein in Mrauk U, Mrauk U District, Rakhine State, Myanmar (Built 1515–1521 CE, Restored 1534–1542 CE, Expanded 1596 or 1606–1607 CE) [Source: File:AndawThein.jpg - Wikimedia Commons]

Temples and temple complexes

Myanmar temples are usually rectangular in shape, although less common pentagonal and octagonal examples also exist.

General characteristics of Myanmar temples

Generally, Myanmar temples are rectangular structures usually with one or more spires. Multiple spires, when present, are usually arranged in cruciform or recursive cruciform fashion with the largest stūpa in centre.

Temples can be simple rectangular structures with spire(s) or may rise as stepped pyramids providing space for single large and multiple smaller spires.

Spires can be in shape of Myanmars-style stūpas or less commonly similar to Indian Nāgara architecture towers. Corner positions of attached halls can also feature similar types of but often less intricate spires.

→ Myanmar-style temples with Nāgara-esque style central tower examples:

Ananda Temple in Bagan, Mandalay Region, Myanmar — faceted paraboloid central tower (Built 1090 CE) [Source: Ananda Pahto Temple, Bagan, Myanmar]

Loka-hteik-pan Temple in Bagan, Mandalay Region, Myanmar (Built 12th century CE) [Source: Loka-hteik-pan Temple, Bagan, Myanmar]

Htilominlo Temple in Bagan, Mandalay Region, Myanmar — features central paraboloid tower surrounded by multiple stūpas (Built 1211 CE) [Source: Htilominlo Temple, Bagan, Myanmar]

Le-myet-hna Temple in Bagan, Mandalay Region, Myanmar — features a Nāgara-esque style central tower surrounded by multiple stūpas (Built 1223 CE) [Source: Le-myet-hna Temple, Bagan, Myanmar]

Wetkyi-in Kubyauk-gyi in Bagan, Mandalay Region, Myanmar — features straight pyramid tower with niches featuring deity sculptures. The shape is similar to the sikhara on the nearby Mahabodhi temple3 located a few km west, which is closer to being a Nāgara architecture temple with Myanmar architecture influence. The art historian Paul Strachan classifies this temple as a lei-myet-hna, or four-faced type, in reference to the solid square core at its center surrounded by four Buddha images, each facing one of the four directions. Unlike similar temples there is no distinction between the east-facing antechamber and the east side of the ambulatory, as there is no intermediary wall between them. By 'dissolving' the wall, the architects created a large enclosed room on the east side of the building directly facing the primary Buddha image. This approach, which made the main Buddha image more accessible to devotees, is carried further on the outer facade where large, spacious doorways provide access on all sides of the building (three of the four sides are now bricked up to prevent off-hours access). Strachan suggests this may have been part of a tendency in later-period temples to downplay mystical interpretations of Buddhist experience (best experienced in dim, cave-like environments) in favor of a lighter, more open, and more rational design, which favored ease of access. (Built early 13th century) [Source: Wetkyi-in Kubyauk-gyi, Bagan, Myanmar]

→ Myanmar style temples with Myanmar-style stūpa central tower examples:

Guyogyo Temple in Bagan, Mandalay Region, Myanmar — features a large central stūpa spire surrounded by 8 small stūpas [Source: Gu-yo-gyo-hpaya Temple, Bagan, Myanmar]

Subsidiary worship halls in Sule Pagoda Complex in Yangon, Myanmar — feature octagonal base stūpas arranged in cruciform pattern [Source: Sule Pagoda, Yangon, Myanmar]

→ Mixed tower styles examples:

Dhammayazika Pagoda in Bagan, Mandalay Region, Myanmar — central stūpa tower with subsidiary spires of both Myanmar-style stūpas and Nāgara-style paraboloid towers (Built 12th century CE) [Source: Bagan - Wikipedia]

Types of temples

Buddhist temples of Bagan

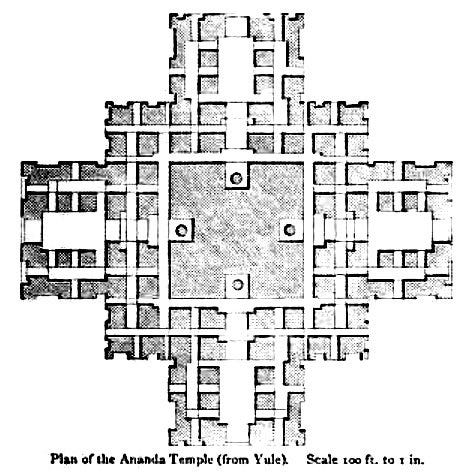

Bagan-style temples can also be divided basis the number of main entrances, termed “faces”: there are one-face, four-face and the much less common five-face temples.

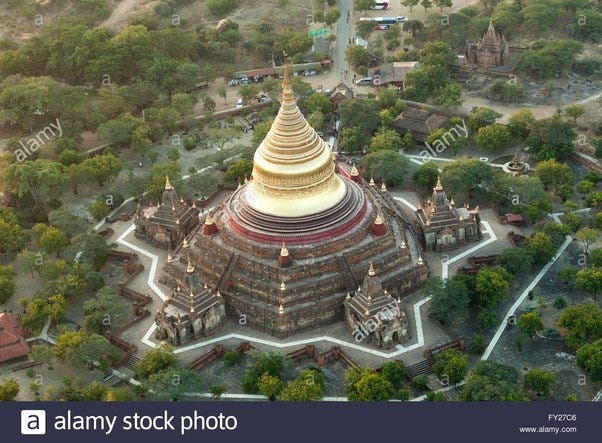

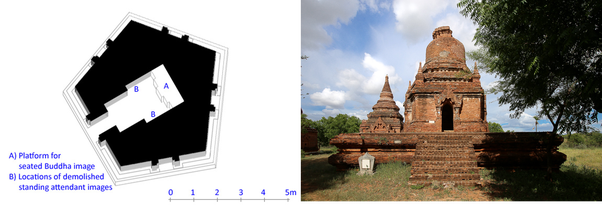

Pentagonal floorplan temples and temple complexes seem to have originated in Bagan Empire period: they are usually either individual pentagonal structures (eg. Dhammayazika Zedi) or groups of structures sharing a pentagonal base (eg. Monument 0566 in Bagan). Such structures are called nga-myet-hna (five-sided).

→ Bagan-style temples and zedis by number of faces examples:

“One-face” type monuments:

Gawdawpalin Temple [Source: Bagan - Wikipedia]

"Four-face" type monuments:

Dhammayangyi Temple [Source: Bagan - Wikipedia]

“5-face” type monuments :

Dhammayazika Pagoda showing the pentagonal plan and the 5 entrances of the main pagoda [Source: Stock Photo - An aerial view of the pentagonal Paya Dhammayazika with its golden dome, in the surroundings of the New Bagan (Myanmar]

Monument 0566 in Bagan, Myanmar — a temple complex with structures arranged over a pentagonal platform (Built 13th century CE) [Source: https://www.orientalarchitecture.com/sid/1445/myanmar/bagan/monument-0566]

Buddhist temples of Mrauk-U

Mrauk U temples usually have single entrance and are somewhat fortified.

→ Mrauk-U temples examples:

Le-myet-hna Temple (Four-Sided Temple) in Mrauk U, Rakhine State, Myanmar — has 4 entrances, one to each cardinal point, and 4 seated Buddhas round a central column. (Built 1430 CE under Narameikhla) [Source: File:Le Myet Hna Temple - Mrauk U.jpg - Wikimedia Commons]

Mahabodhi Shwegu Temple in Mrauk U, Rakhine State, Myanmar — a single entrance temple with an octagonal bell shaped tower (Built late 15th century CE under king Ba Saw Phyu) [Source: Mahabodhi Shwegu temple]

Shite-thaung Temple in Mrauk-U, Mrauk-U District, Rakhine State, Myanmar [Source: Shite-thaung Temple - Wikipedia]

Koe-thaung Temple Complex in Mrauk U, Mrauk U District, Rakhine State, Myanmar — the load bearing semi-circular arches inside indicate that Mrauk U retained or independently adopted arches after their use declined in Bagan Empire’s territories. (Built 1554–1556 CE under king Dikkha) [Source: Koe-thaung Temple - Myanmar Tours]

Htuk-Kan-Thein in Mrauk U, Mrauk U District, Rakhine State, Myanmar — built like a fort, the main stūpa is located towards the back of the temple. While the outer portion has multiple entrances reached via stairs, the inner portion itself has only one. (Built 1571 CE) [Source: File:HtukKanThein.jpg - Wikimedia Commons]

Arrangement plans of temple complexes

Myanmar style temple complexes usually consist of a central temple surrounded by multiple subsidiary structures. A temple complex can have a central temple or central zedi (forming a “pagoda complex” to be precise) along with one or more subsidiary structures including smaller zedis, true stūpas, worship halls, subsidiary temples and pavilions. These structures can be surrounded by one or more enclosures, having gates usually in cardinal directions.

A few complexes consist of paired main structures : paired temples, paired zedis, or a temple & a zedi. Less common complexes like Paya-thon-zu consist of triplets of main structures

→ Myanmar Temple Complexes examples:

Aerial view of Kuthodaw Pagoda Complex & Sandar Muni Pagoda Complex in Mandalay, Mandalay district, Mandalay Region, Myanmar — both complexes are rectangular with 4 entrances and a large central zedi [Source: File:Ku Tho Taw Pagoda & Sandar Muni Pagoda, Mandalay.jpg]

Payathonzu Temple Complex of Bagan — consists of 3 temples conjoined through narrow passages [Source: Payathonzu Temple - Wikipedia]

Myanmar Temple and Temple Complexes floorplans

Floorplans of Myanmar style temples are usually rectangular, with entrances on either 1 or all 4 sides. In cases where a connected hall exists, there can be upto 6 entrances: 3 in the connected hall and 3 in the main temple structure itself.

Pentagonal floorplan temples and temple complexes seem to have originated in Bagan Empire period: they are usually either individual pentagonal structures (eg. Dhammayazika Zedi) or groups of structures sharing a pentagonal base (eg. Monument 0566 in Bagan). Such structures are called nga-myet-hna (five-sided).

→ Cruciform floorplan temples examples:

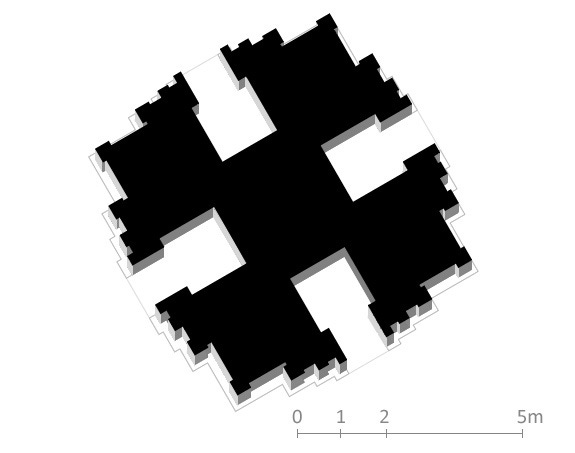

Axonometric Cutaway of Monument 1375 in Bagan, Mandalay Region, Myanmar [Source: Monument 1375, Bagan, Myanmar]

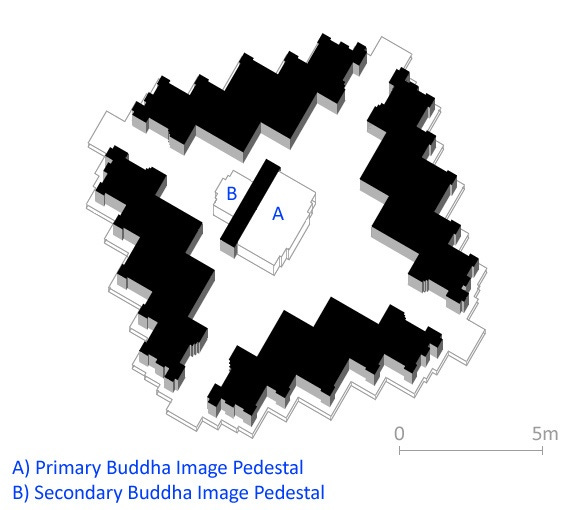

Axonometric Cutaway of Guyogyo Temple of Bagan showing its 4 entrances and Buddha image pedestals [Source: Gu-yo-gyo-hpaya Temple, Bagan, Myanmar]

Plan of Ananda Temple in Bagan, Mandalay Region, Myanmar [Source: File:Plan of Ananda Temple Myanmar.jpg]

→ Extended Cruciform floorplan temples examples:

Floorplan of Kathapa Temple in Bagan, Mandalay Region, Myanmar — the attached hall has 3 entrances while the main structure also has its own additional 3 entrances [Source: Kathapa-hpaya, Bagan, Myanmar]

→ Pentagonal temples examples:

Pentagonal Monument 0566 in Bagan, Mandalay Region, Myanmar — there is a single stairway to from the base to the structures [Source: Monument 0566, Bagan, Myanmar]

Nga-myet-hna Temple in Bagan, Mandalay Region, Myanmar — there are 5 entrances, 1 on each side [Source: Nga-myet-hna Temple, Bagan, Myanmar]

→ Other floorplans examples:

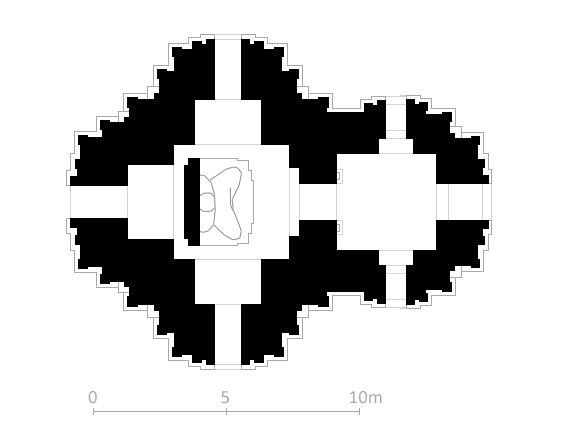

Floorplan of Paya-thon-zu in Bagan, Mandalay Region, Myanmar [Source: Paya-thon-zu Temple, Bagan, Myanmar]

→ Myanmar Temple Complexes floorplans examples:

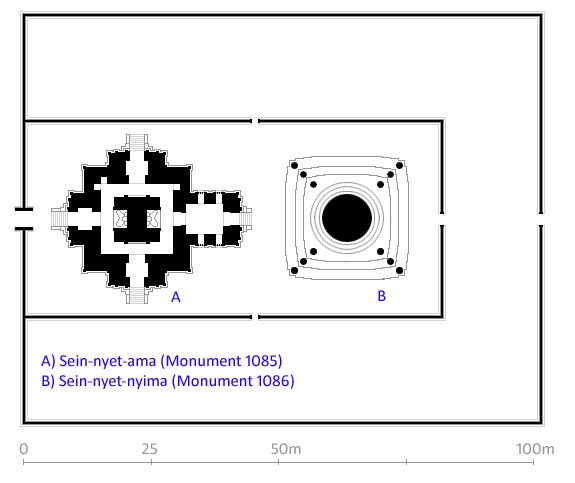

Symmetric floorplan of Sein-Nyet-Ama & Sein-Nyet-Nyima Temple Complex in Bagan, Myanmar — consists of an extended cruciform floorplan temple and a square floorplan stūpa [Source: Sein-Nyet-Ama & Nyima Temples, Bagan, Myanmar]

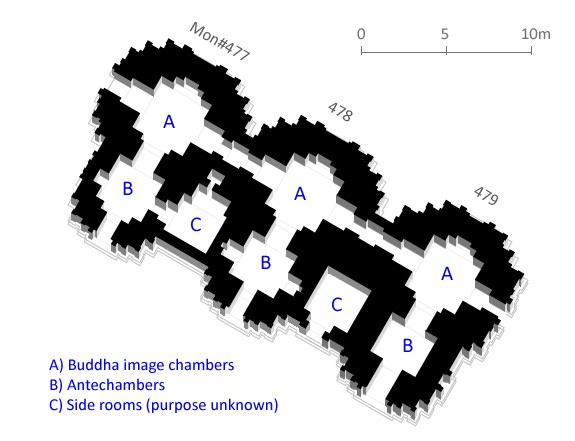

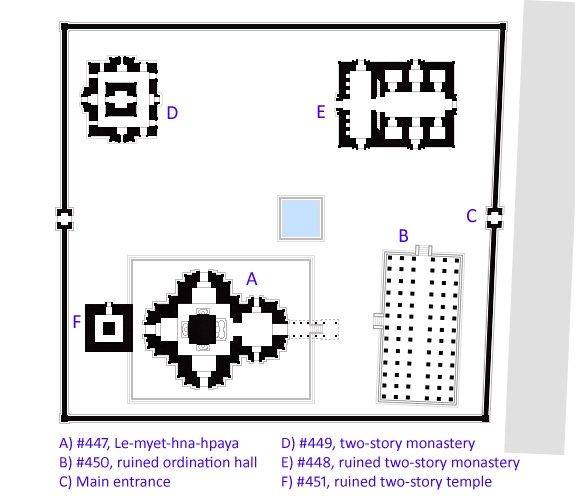

Floorplan of Lemyethna Temple Complex in Bagan, Mandalay Region, Myanmar — the individual structures are largely symmetrical but the complex in its entirety is not. [Source: Le-myet-hna Temple, Bagan, Myanmar]

Kyaung (ဘုန်းကြီးကျောင်း; Monastery)

Kyaung is a monastery comprising the domestic quarters and workplaces of Buddhist monks. They are typically built of wood, meaning that few historical monasteries built before 1800s CE survive.

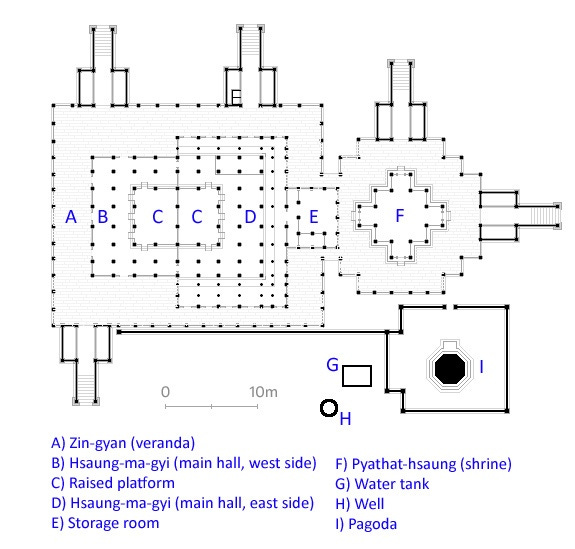

The typical kyaung consists of a number of buildings called kyaung zaung (ကျောင်းဆောင်):

Zedi (pagoda, as described above)

Shrines to the arhats Sīvali and Shin Upagutta

Tagundaing (တံခွန်တိုင်) — ornamented flagstaff celebrating the submission of local nats (animistic spirits) to the Dhamma

Cooking quarters

Living quarters for the monks and the sayadaw (senior monks and abbots)

Various pavilions and halls including following:

Gandhakuti (ဂန္ဓကုဋိ, from Pali gandhakuṭi) — pavilion that houses the monastery's principal image of the Buddha

{Traditional Konbaung era monasteries had Buddha images in Pyatthat hsaung [See below]}Dhammayon (ဓမ္မာရုံ) — assembly hall used for sermons and communal purposes

Thein (သိမ်, from Pali sīmā) — ordination hall as prescribed by the Vinaya

Sim (သိမ်ႇ) are Shan ordination halls and are exclusively used for events limited to the monkhood

Kyetthayei khan (ကျက်သရေခန်း) — storage room

Zayat (ဇရပ်) — open-air pavilions used as rest houses.

Zayats are not unique to kyaungs or to Buddhism, but can be found as standalone structures or as part of non-Buddhist religious complexes.Traditional monasteries of Konbaung era consisted of the following halls:

Pyatthat hsaung (ပြာသာဒ်ဆောင်) — main chapel hall that housed images of the Buddha

Hsaungmagyi (ဆောင်မကြီး) or hsaungma (ဆောင်မ) — main assembly hall for lectures, ceremonies and housing junior monks

Sanu hsaung (စနုဆောင်) — residential hall of the monastery abbot

Bawga hsaung (ဘောဂဆောင်) — storage room for monks' provisions

In pre-colonial times, royal monasteries were organized as complexes known as kyaung taik (ကျောင်းတိုက်), composed of several residential buildings, including the main building, kyaunggyi (ကျောင်းကြီး) or kyaungma (ကျောင်းမ), which was occupied by the residing sayadaw, and smaller structures called kyaungyan (ကျောင်းရံ), which housed the sayadaw's disciples. The complexes were walled compounds, and also housed a library, ordination halls, meeting halls, water reservoirs and wells, and utility buildings.

Parts of monasteries

Parts of pre-Konbaung period monasteries

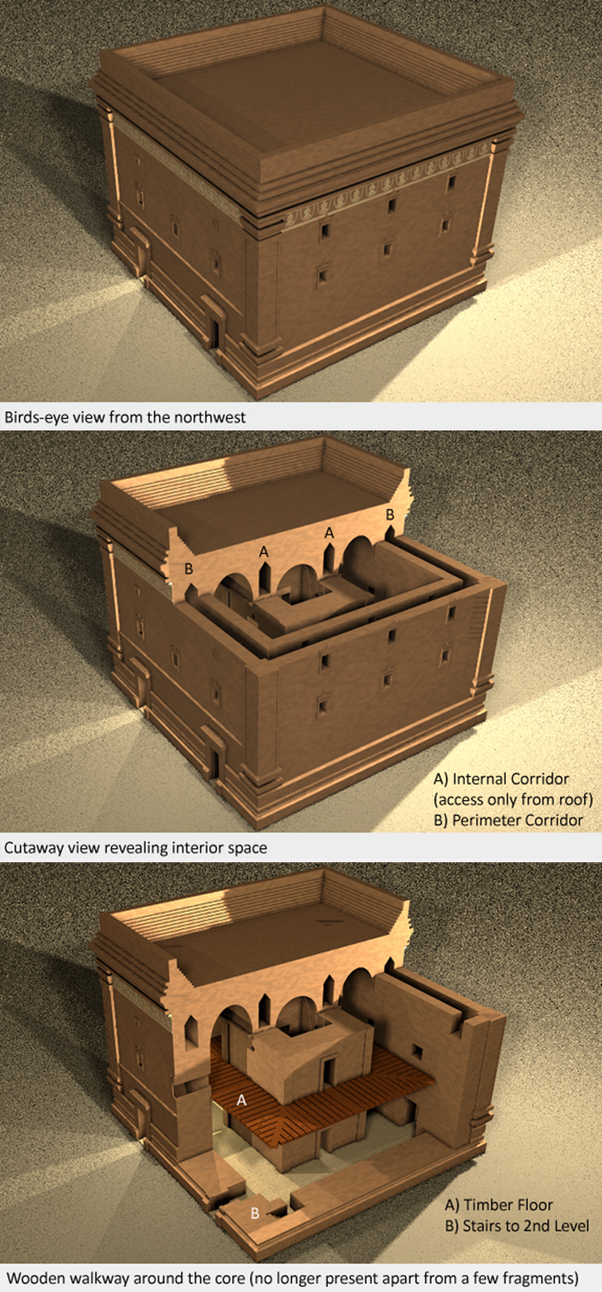

→ Shin-bo-me-ok-kyaung Monastery in Bagan, Mandalay Region, Myanmar [Source: Shin-bo-me-ok-kyaung Monastery, Bagan, Myanmar]

The brick structure is the only part that survives. The holes were anchor points for wooden pavilion which no longer survives

Cutaway 3D renderings

Parts of Konbaung period monasteries

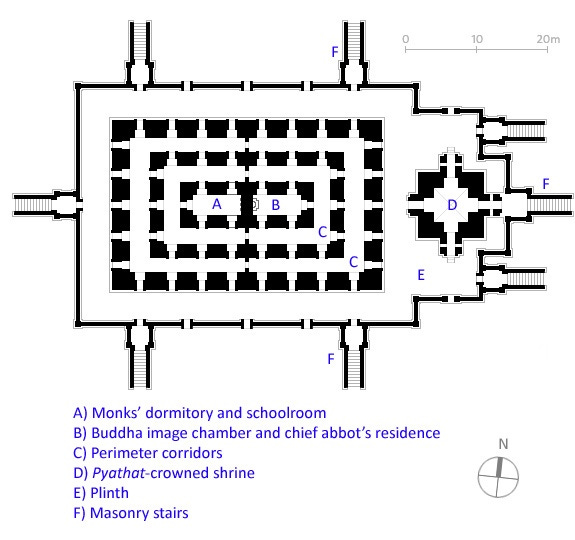

Traditional monasteries of Konbaung era consisted of the following halls:

Pyatthat hsaung (ပြာသာဒ်ဆောင်) — main chapel hall that housed images of the Buddha

Hsaungmagyi (ဆောင်မကြီး) or hsaungma (ဆောင်မ) — main assembly hall for lectures, ceremonies and housing junior monks

Sanu hsaung (စနုဆောင်) — residential hall of the monastery abbot

Bawga hsaung (ဘောဂဆောင်) — storage room for monks' provisions

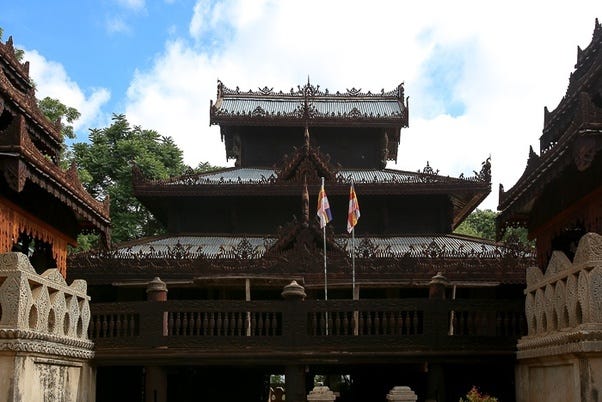

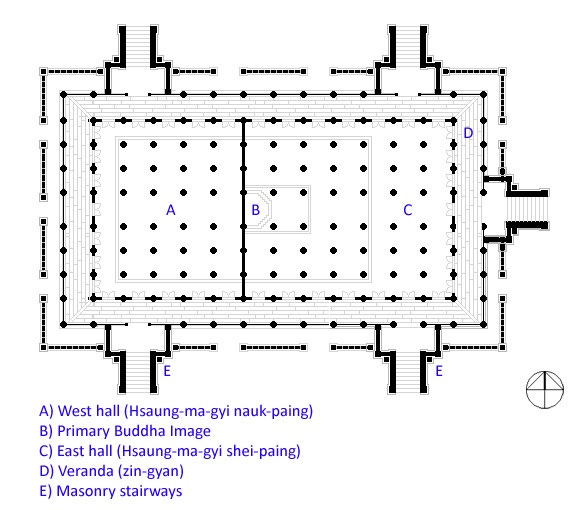

→ Parts of Shwe In Bin Kyaung in Mandalay, Mandalay Region, Myanmar (Built 1894 CE) [Source: Shwe In Bin Kyaung Monastery, Mandalay, Myanmar]

7-tiered Pyatthat hsaung

Hsaungmagyi — measures 32m long, crowned by 3 tiers of zei-ta-wun style roofs

Bawga hsaung

Covered Passageway between dormitory (left) and store room (right)

→ Parts of Nat Taun Kyaung in Mandalay, Mandalay Region, Myanmar (Built CE) [Source: Nat Taung Kyaung Monastery, Bagan, Myanmar]

Entire Complex

Pyatthat Hsaung

Hsaungmagyi — crowned by 3 tiers of zei-ta-wun style roof

Kyaung views and floorplans

→ Kyaung examples:

Somingyiok Monastery in Bagan, Mandalay Region, Myanmar (Built 12th century CE) [Source: So-min-gyi-ok-kyaung Monastery, Bagan, Myanmar]

Yokesone Monastery of Salay, Magwe Region, Myanmar is known for its abundance of woodcarvings which depict scenes of the Jataka tales (most structures built in 1882 CE) [Source: File:Yokesone Monastery, Salay, built in 1882.jpg]

→ Kyaung floorplans examples:

Floorplan of Maha Aung Mye Bonzan Monastery in Inwa, Mandalay Region, Myanmar [Source: Maha Aung Mye Bonzan Monastery, Inwa (Ava), Myanmar]

Floorplan of Shwenandaw Kyaung in Mandalay, Mandalay Region, Myanmar [Source: Shwenandaw Kyaung Temple, Mandalay, Myanmar]

Floorplan of Bagaya Kyaung in Inwa, Mandalay Region, Myanmar [Source: Bagaya Kyaung Monastery, Inwa, Myanmar]

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pyu_city-states

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Nanzhao

https://orientalarchitecture.com/sid/522/myanmar/bagan/mahabodhi-paya