Temple Architecture Styles : Parθavan architecture

Parθava Empire (247 BCE – 224 CE) initiated some of the earliest large scale temple building in ancient Iran. Their architecture shows influence of Hellenic, Biritumian (Mesopotamian), Kemetian (Egyptian) and earlier Iranian architecture, in particular that of Haxāmanišyaʰ Empire (550 BCE – 330 BCE) whose architectural developments are more related to non-religious sites.

Darayanids (2nd century BCE – 224 CE) ruled as Parθavan vassals in Fars region until they toppled them to establish Ērānšahr (Sāsānian dynasty).

→ Parθava Empire in 94 BCE at its greatest extent, during the reign of Mihrdāt II (r. 124 BCE – 291 BCE) [Source: File:Map of the Parthian Empire under Mithridates II.svg]

Development History

Pre-Parθavan Influence

Early Works of Elam & Šušan:

For some few thousand years before 3rd millennium BCE, the region of Šušan was inhabited by nomadic and semi-nomadic peoples who eventually settled and founded the city of Šušin ~4395 BCE. Elamites were already in the region at this time, their settlement at Chogha Bonut dating to ~7200 BCE. These peoples’ lives on Iranian Plateau were alternately influenced by Saĝ-gíg (Sumerians) of Biritum (Mesopotamia) and the tribes of the highlands of Zagros mountains.

By this time, a type of art had already developed in the region which is now known as Proto-Elamite (~3100-2700 BCE) and focused chiefly on depictions of animals — this is recognized as earliest Iranian civilization.

→ Proto-Elamite animal figurines: Left to right —

Guennol Lioness [Source: File:Guennol Lioness.jpg]

Bull kneeling with vessel [Source: File:Proto-Elamite kneeling bull holding a spouted vessel.jpg]

A striding figurine [Source: File:Striding Figure Proto-Elamite period.jpg]

Proto-Elamite Period ended with encroachments from Biritum during their Early Dynastic Period (2099-2334 BCE) and, especially, during Dynastic III Period (2600-2334 BCE) when Saĝgígan kings like Éannatum (~2500-2400 BCE) conquered Elam. Biritumian influence at this time is evident in statuary representing human figures, most notably statuettes of worshippers placed in sanctuaries to represent the spirit of communal devotion.

Māt Akkadi took the region under its founder Šarrugi (r. 2334-2279 BCE) further advancing Biritumian motifs in the art of the region and, in architecture, this influence was manifest most clearly in the great building complex of Chogha Zanbil, built during the reign of Untash-Napirisha (r. c. 1340 BCE).

Chogha Zanbil is a Biritumian ziggurat surrounded by temples and encircled by a wall. Made of baked clay bricks, and inscribed with Elamite phrases, praises, and curses, the complex was an attempt to unify the disparate regions of Elam in worship of the deity Inšušinak (𒀭𒈹𒂞𒆠 ; Lord of Šušin), patron deity of Šušin. Chogha Zanbil drew on Birituamian motifs and methods of construction which would be developed later in Iranian art and architecture.

→ Chogha Zanbil in Khuzestan province, Iran — one of the few existing ziggurats outside Biritumian region. [Source: File:زیگورات چغا زنبیل.jpg]

→

Middle-Elamite model of a sun ritual, Šušin, ~1150 BCE [Source: File:Susa, Middle-Elamite model of a sun ritual, circa 1150 BCE.jpg - Wikimedia Commons]

Middle-Elamite bas-relief of warrior deities, Šušin, 1600-1100 BCE [Source: File:Susa, Middle-Elamite basrelief of warrior gods 1600-1100 BCE.jpg - Wikimedia Commons]

Māda Empire (8th century BCE – 6th century BCE):

Medians (Māda) were an ancient Iranian people who spoke the Median language and who inhabited an area known as Media between western and northern Iran. ~11th century BCE, they occupied the mountainous region of northwestern Iran and the northeastern and eastern region of Biritum located in the region of Hamadan (Ecbatana). Their emergence in Iran is believed to have occurred ~8th century BCE. In 7th century BCE, all of western Iran and some other territories were under Median rule, but their precise geographic extent remains unknown.

The influence of Medians remains the least known among the Pre-Parθavan influence. They might have been influential in bringing Aššuran-era Biritum influence to Iran, being instrumental in the fall of Second Aššur Empire (911 BCE – 609 BCE) in collusion with Babylonians. Aššuran influence can be later seen in Haxāmanišyaʰ-era buildings, particularly Lamassu motifs.

Haxāmanišyaʰ Empire (550 BCE – 330 BCE):

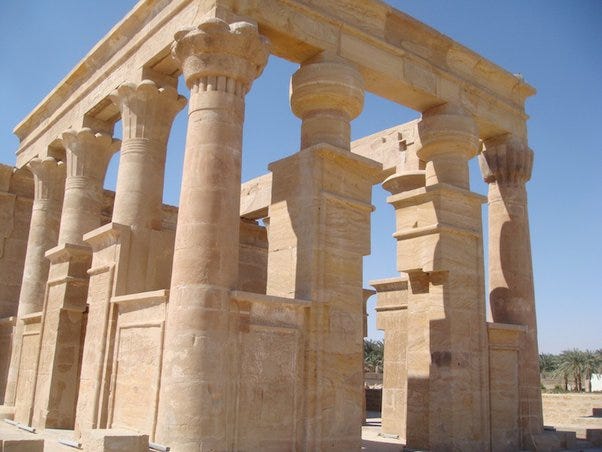

Haxāmanišyaʰ Empire (Ariya: 𐎧𐏁𐏂, romanized: Xšāça ; Empire) was founded by Kūruš II when he gained independence from Medians. Later encompassing parts of Egypt, Kemetian architecture influence reached the empire during that period.

When Dārayavaʰuš I came to power, he rebuilt Šušin, adding a palace complex to the site, and followed the same paradigm as Kūruš II had in featuring elaborate gardens as central to the design. In his buildings at Šušin and Pārsa, Dārayavaʰuš I’s artisans initiated the motif of the “Iranian animal capital” – the figure of a bull or a bird at the top of a column – and also designed these columns as slender pieces which would draw the eye upwards to the capital figure while also accentuating the grandeur of the height of the building. Post-and-Beam construction was used for the roof, which – at Pārsa – was made of cedar from the forests of Lebanon. Dārayavaʰuš I also initiated the practice of ornamentation by bas-relief. The most famous bas-relief at Pārsa shows the many different people of Haxāmanišyaʰ Empire arriving to pay homage to Iranian emperor, and these images are detailed enough that the nationality of each individual is easily discerned as are the gifts they are shown bringing as offerings.

→ Amun’s Temple of Hibis in Kharga Oasis, Western Desert, New Valley Governorate, Egypt — it was constructed on orders of Dārayavaʰuš I (locally also known as Pharaoh Deriush Setut-Ra in Kemet) [Source: Hibis Temple - Kharga]

→ Ruins of Apadāna Hall, a large hypostyle hall in Persepolis, Marvdasht, Fars Province, Iran. The hypostyle characteristic shows Hellenic influence on the empire [Source: File:Persepolis001.jpg - Wikimedia Commons]

→ This limestone wall relief shows a Mede man holding a gift, which appears to be a lamb, for the king. The event is probably the Iranian New Year (Newroz). From Pārsa, the stairway of Palace of Xšayār̥šā I (r. 486 BCE – 465 BCE) [Source: ancient.eu]

Starting sometime before Second Aššur Empire, Assyrians developed a form for Birit Narim protective deity Lamassu with wings, 4-legged lion/bull body and human head. This was adopted in some places by Haxāmanišyaʰ Empire.

→ Lamassu at the Gate of All Nations in Persepolis. [Source: File:Persepolis 24.11.2009 11-17-28.jpg]

→ A recreation of the details of the 4-winged figure on Tomb of Kūruš (in Pasargadae, Fars Province, Iran) in Olympic Park, Sydney, Australia — the original is a bas-relief cut upon a stone slab depicting a figure or a guardian man, most likely a resemblance of Kūruš himself, possessing 4-wings shown in an Assyrian style, dressed in Elamite traditional clothing, assuming a pose and figure of an Kemetian deity, and wearing a crown that has 2 horns. [Source: File:Olympic Park Cyrus-2.png]

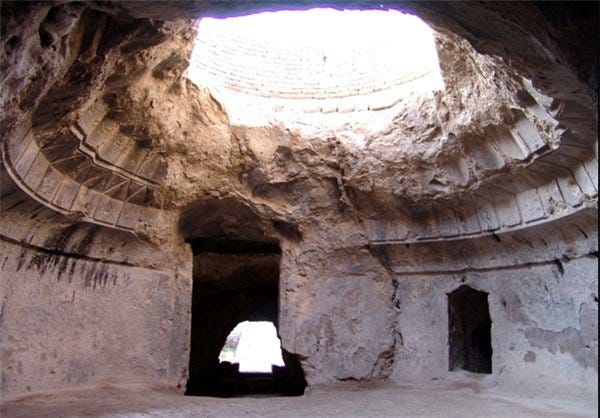

Rulers of Haxāmanišyaʰ Empire held audiences and festivals in domical tents derived from the nomadic traditions of central Asia. They were likely similar to the later tents of Mongγol Khans. Called "Heavens", these tents emphasized the cosmic significance of the divine ruler. They were adopted by Alexandros III of Makedonia after his conquest of the empire, and the domed baldachin of Roman and Byzantine practice was presumably inspired by this association. These domical tents would have been the precursor/inspiration for Parθavan-era domes.

Basileía tōn Seleukidōn (312 BCE – 63 BCE):

Alexandros III of Makedonia conquered most of Haxāmanišyaʰ empire by 330 BCE. Upon Alexandros III's death, most of the empire's former territory fell under the rule of Ptolemaïkḕ basileía and Basileía tōn Seleukidōn, in addition to other minor territories which gained independence at that time.

Basileía tōn Seleukidōn brought a much higher degree of Hellenic influence to Iran and Iraq, to the point that early Parθavan art and architecture is more or less Hellenic in character.

Mihrdāt I conquered much of the eastern lands of Basileía tōn Seleukidōn in mid-2nd century BCE, while the independent Diodotid Bactrian Kingdom continued to flourish in the northeast. Seleukid kings were thereafter reduced to a rump state in Syria, until their conquest by Tigran II of Armenia in 83 BCE and ultimate overthrow by the Roman general Gnaeus Pompeius Magnus in 63 BCE.

Hellenistic Phase

At the beginning of their history, Parθavan art was still very much influenced and likened to Hellenic art. Especially in the earliest Parθavan capital of Nisa evidence could be discovered from the early Parθavan period indicating the similarities to Hellenic culture. Most finds there date to 1st three centuries BCE. There were purely Hellenic marble sculptures and a series of ivory rhytons in Hellenistic style with figuratively decorated designs.

Although Parθavans retained the basics of Haxāmanišyaʰ artworks, their vision was expressed in circularity in architecture and frontality in art. The bas-reliefs of Haxāmanišyaʰs – featuring images of people from the side – were replaced by statuary and images which meet a viewer face-to-face. One notable example of this is the frontal bas-relief of a Parθavan king offering sacrifice to the deity Heracles-Verethragna, patron deity of royal dynasties (presently housed in Louvre Museum, Paris, France — the king holds a cornucopia in his left arm while his right offers a sacrifice at a Fire Altar. This image, like many, once adorned a temple dedicated to the deity.

The strong frontal orientation of Parθavan art is unusual for Western Asia and seems to be influenced by the presence of Hellenic art.

→ Frontal bas-relief of Parθavan king offering sacrifice to Heracles-Verethragna — the king holds a cornucopia in his left arm while his right offers a sacrifice at a Fire Altar [Source: ancient.eu]

Parθavan Phase (1st century CE onwards)

It can be determined that ~1st century CE in Parθavan Empire a new style characterized mainly by frontal views of the figures, veering away from earlier Hellenic models. It appears to have originated in Biritum, in particular Babylon.

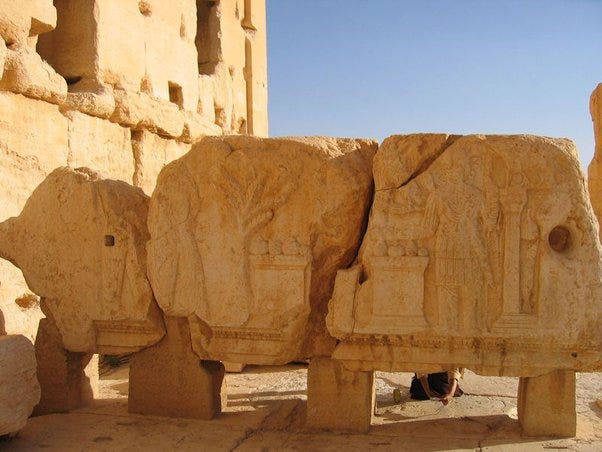

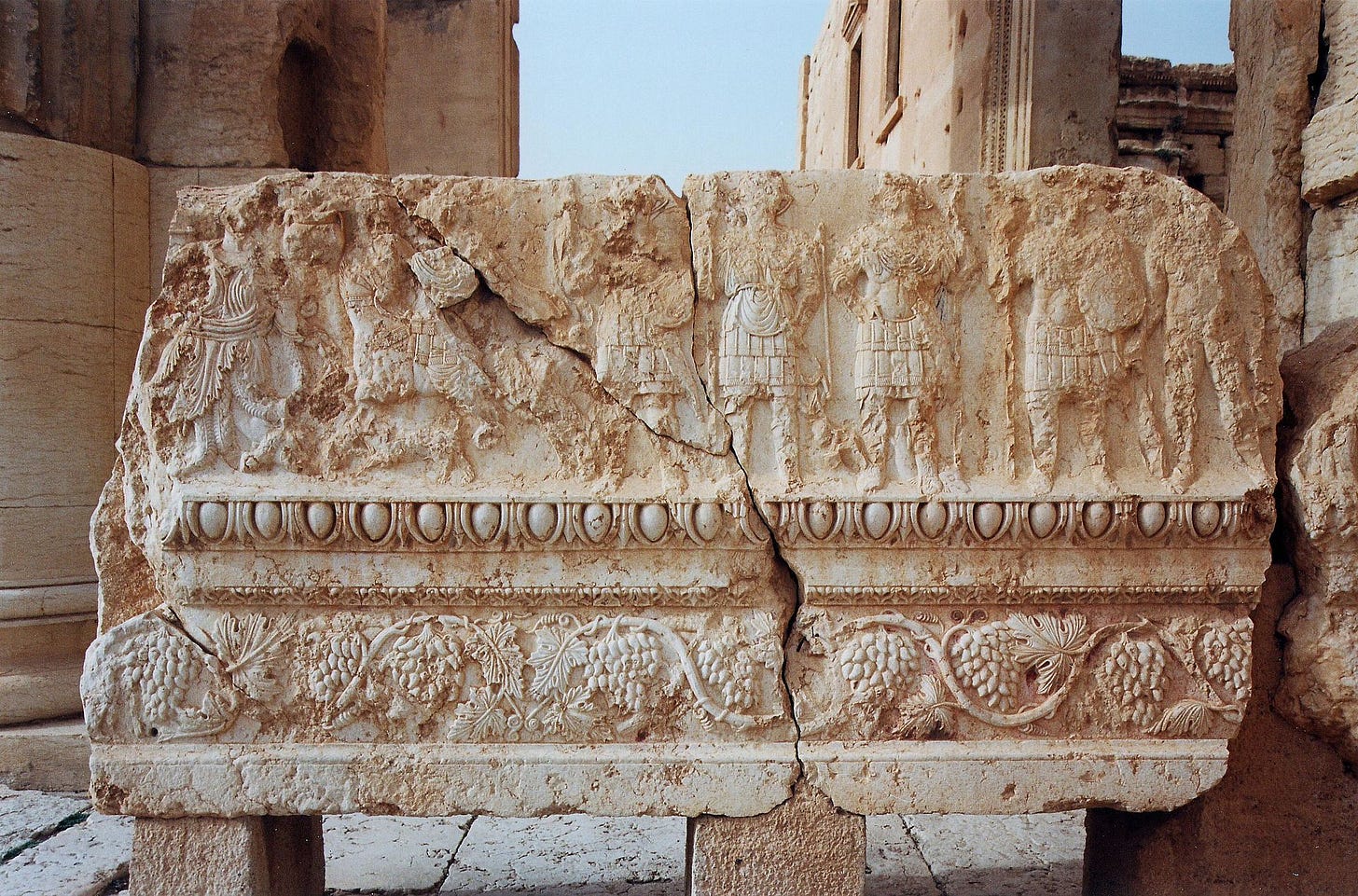

→ Relief on Baal Temple in Palmyra, Syria [Source: File:Frieze in the Temple of Bel Palmyra Syria.JPG]

Parθavans started the use of the structure called ‘Ayvān ’ on a monumental scale — ayvān is a barrel-vault-roofed hall, usually preceding the main building containing the sanctum of a temple. One of the earliest Parθavan ayvāns was found at Seleúkeia (Seleúkeia-on-the-Tigris), located on Tigris River, where the shift from post-and-lintel construction to vaulting occurred ~1st century CE. Other early ayvāns have been suggested at Aššur, where 2 buildings containing ayvān-like foundations were found. The first building, located near the ruins of a ziggurat, featured a 3-ayvān façade. Parθavan ayvān led to other spaces, but its primary function served as a room itself. Ayvān would later be adopted by Sāsānians and later empires centred in Iran.

Parθavans may also have been inventors of squinch, beginning the construction of Iranian domes. The remains of a large domed circular hall measuring 17m in diameter in the Parθavan capital city of Nisa has been dated to ~1st century CE.

→ Ruins of a Mazdaist Temple in Maragheh, Maragheh County, East Azerbaijan Province, Iran (~200 CE) [Source: File:Niyayeshgah-e Mehri Maragheh.jpg]

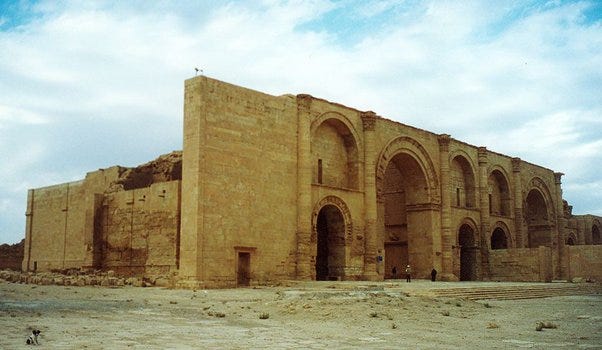

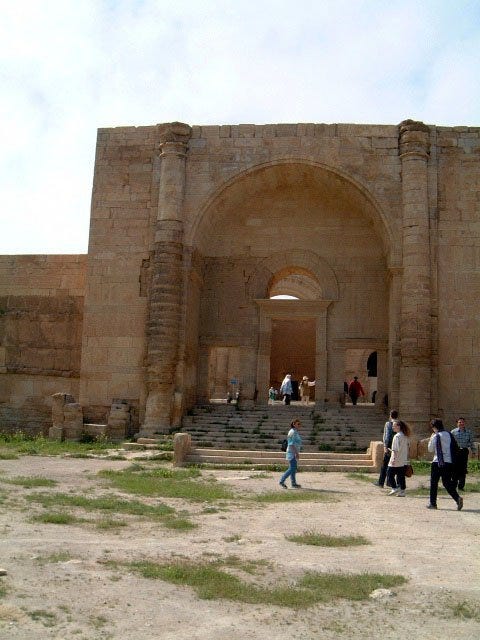

In 2nd century CE, Kingdom of Hatra flourished usually under Parθavan suzerainty, in present-day Hatra District, Nineveh Governorate, Iraq. Parθavan Sun Temple at Hatra appears to indicate a transition from columned halls with trabeated roofing to vaulted and domed construction in 1st century CE, at least in Biritum. The domed sanctuary hall of the temple was preceded by a barrel vaulted ayvān, a combination that would be used by the subsequent Iranian Sāsānian Empire.

→ Detail of a temple in Hatra, showing Hellenistic, Biritumian, Iranian, and Roman architecture influence [Source: File:Hatra-1454.jpg - Wikimedia Commons]

→ Ayvāns in Hatra [Source: File:Hatra-109726.jpg - Wikimedia Commons]

→ Parθavan Sun Temple in Hatra [Source: ancient.eu]

Structural Details

Motifs and sculptures

Wall surfaces at Aššur were adorned with tooled stucco using geometric and floral patterns that are a precursor of designs adopted by Mohammedan artists.

The first genuine Parθavan art, found at Mithradatkert/Nisa, combined elements of Hellenic and Iranian art in line with Haxāmanišyaʰ and Seleukid traditions.

In the second phase, Parθavan art found inspiration in Haxāmanišyaʰ art, as exemplified by the investiture relief of Mihrdāt II at Mount Behistun.

The third phase occurred gradually after the Parθavan conquest of Biritum.

→ Parθavan motif at Aššur [Source: ancient.eu]

→ Temple wall paintings examples:

The sacrifice of Konon, wall painting in the Temple of Bel in Dura Europos, Syria [Source: File:Dura Europos fresco Sacrifice of Conon.jpg]

→ Temple wall sculptures examples:

Decorated arches with faces found in Hatra, Iraq [Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hatra]

Relief at the courtyard of the temple showing detailed ornaments and depictions of Palmyrene war deities [Source: https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/5/59/PALMYRA_Tempio_di_Baal_particolare_del_fregio_con_sfilata_degli_dei_-_GAR_-_6-057.jpg/1920px-PALMYRA_Tempio_di_Baal_particolare_del_fregio_con_sfilata_degli_dei_-_GAR_-_6-057.jpg]

Materials

Bricks stacked on edge in groups, alternating with others in horizontal lays, were quite common in the mud-brick architecture of Second Saĝ-gígan Empire period in Biritum (3rd millennium BCE) — Parθavan version of this technique, used occasionally for walls and columns, employed baked brick with each course built alternating between vertical and horizontal lays, ignoring the bonding properties of flat brick where the joints are laid overlapping both lengthwise and laterally through the wall.

Quoting from https://www.iranicaonline.org/articles/architecture-ii/:

To build strong wall foundations, deep trenches for wall footings were dug and elaborate systems of platforming were constructed, to support structures above; these platforms appear in a variety of forms, suggesting that there was no architectural standard that builders followed.

Similarly, to build strong wall foundations, deep trenches for wall footings were dug and elaborate systems of platforming were constructed, to support structures above; yet these platforms appear in a variety of forms, suggesting that there was no architectural standard that builders followed. Often, at mound sites with an upper layer of Parθavan or late Iron Age date it is only remnants of these platforms which survive, resulting in confusion for the archaeologists should the matrix of walls and fill be confused with occupational remains. In some cases where massive platforms have been called for, the execution of the project has defeated the purpose behind the plan. This is especially true where a platform has been designed to project out from an existing elevation, forming an extended terrace. There is a danger here that the sheer weight of the added mass is so heavy that it is torn away from the core to which it is supposed to be anchored. To use brick sizes as a way of dating archaeological remains of the Parθavan period is unwise: there are generalities one can observe, even local characteristics that repeat themselves, but such dimensions can not be used outside of the area to date other ruins because the concept of standards does not apply.

Halls and Pavilions

Ayvān

Ayvān12 is a rectangular hall or space, usually vaulted, walled on three sides, with one end entirely open. The formal gateway to the ayvān is called pištaq, an Iranian term for a portal projecting from the façade of a building.

The problem of the heavy lateral thrust of brick vaulting was solved by flanking corridors which buttressed the main vault by carrying the thrust out through a series of parallel side walls.

→ A barrel vaulted ayvān at the entrance at the ancient site of Hatra (built 50 CE) [Source: File:Hatra (17).jpg]

Temples and Temple Complexes

In Parθavan temples, usually an ayvān would lead to a sanctum. The temple walls would be adorned by paintings and sculptures, usually facing the viewers.

Quoting from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Parthian_art#Architecture:

The temple of the Sun Mithras in Hatra resembles features a mix of a Birtumian and Helleno-Roman temple architecture — this kind of juxtaposition of certain classical structures is a Parθavan feature. A Cella standing at a podium is surrounded on three sides by two rows of columns. The front is adorned by a staircase, which is flanked on the sides of the outer row of columns. The outer row of pillars standing on the base and is decorated with compositional chapters. The inner row of columns stands on the podium and has Ionic capitals. The pediment of the temple front shows a bow. The architraves and pediments are richly decorated with architectural decoration.

A similar temple was found in Assyria, consisting of 3 consecutive rooms with the Blessed Sacrament as the last room. Around the temple columns are present resembling a Helenic architecture temple. The fact that the columns are only on three sides, and that the front was not decorated with columns indicates a particularly Parθavan fashion. In many Hellenic temples, columns would not be present on one side, but that would rarely be the entrance or front of the temple.

Other temples seem to be built more on ancient Eastern traditions. In the center of the temple complex of Hatra is a series of juxtaposed arches, with two main arches, flanked by several small rooms. There are also 6 smaller arches in the surrounding space. The complex is also on an elevated podium. The facade is divided by pilasters. It features rich architectural decorations, especially sculptures of humans and of animals.

→ Parθavan temples in Hatra:

Beit ʾElāhā (House of Deity) dedicated to solar deity Šamaš in Hatra, Nineveh Governorate, northern Iraq. [Source: ancient.eu]

In Uruk there still stands the Temple of Gareus dedicated to an otherwise unknown deity Gareus3, and built entirely of burnt brick. The dimensions are 10.7 × 13.7 metres. The original height of the structure is unknown, but the surviving ruins of the structure are over eight metres high. The exterior was decorated with four half-columns with Ionic capitals and vaulted niches in between. In front of the temple's facade, there was a series of 6 columns.

→ Parθavan Temple of Gareus4 in Uruk, Al-Warka, Muthanna Governorate, Iraq. This temple is built entirely of burnt brick. The dimensions are 10.7 × 13.7 metres. The original height of the structure is unknown, but the surviving ruins of the structure are >8m high. The exterior was decorated with four half-columns with Ionic capitals and vaulted niches in between. In front of the temple's facade, there was a series of 6 columns. (Built c. 110 CE) [Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Temple_of_Gareus]

The temples at Dura Europos are architecturally relatively simple. There were several rooms arranged around a central courtyard. The 'Holy of Holies' was located mostly on the back of the unit and could be noted by columns at the entrance. The other rooms around the courtyard were used for banquets, as a priest's chamber, or as places of worship . The Blessed Sacrament was often painted magnificently.

→ Bel Temple Complex at Duro-Europos, Syria. The northern and western walls of the temple are formed by the city wall. The sanctum sanctorum was located in the west. The original construction phase consisted of a wide room, to which a vestibule was added in the second building phase. In front of the sanctum sanctorum was a courtyard, surrounded by various rooms, whose function is yet unclear. The main entrance to the temple was located on the east side of sanctuary, roughly opposite the sanctum sanctorum. [Source: File:DuraEuropos-TempleOfBel.jpg - Wikimedia Commons]

References

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Iwan

https://www.iranicaonline.org/articles/ayvan-palace/

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Gareus

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Temple_of_Gareus