Temple Architecture Styles: Karnāṭa Architecture Style

Karnāṭa Architecture is the branch of Vesara Architecture1 corresponding to Karnāṭa region’s temple architecture style.

Vesara architecture temples can have attached halls wider than the vimāna(s). Superstructures are primarily allowed as part of vimāna(s), over the attached halls (but lower in height than vimāna(s)), over the entrances of halls and/or vimāna(s) as applicable and over gateways. For an individual temple, the vimāna(s) are the highest part, but for a temple complex, gateways can higher, especially when added at later time periods.

In general, for a given Vesara architecture temple, one vimāna has one sanctum sanctorum, but one temple can have multiple vimānas. Notable exceptions to this rule include Halasi’s Bhuvaraha Narasimhaswamy Temple whose single vimāna has 2 sancta.

→ General superstrutures of a Vesara architecture temple highlighted below [Source: Sri Bhuvaraha Narasimha Temple, Halasi – Temples of Karnataka ]

Development

4th century CE – 6th century CE

Banavasi Kadambas (345 CE – 540 CE)

Temples:

While most other architecture features from preceding periods were gradually abandoned, Candraśālā arch in particular continued to be used and was developed into various types of motifs. The second phase of Ajanta caves was completed under Vākāṭakas in 5th century CE. These caves developed on the existing Candraśālā arch motifs and entrance decorations.

However, it is Kadamba architecture which can be considered the origin point of Karnāṭa architecture. Kadamba dynasty’s most significant contribution was the development of Kadamba śikhara — tower rising in steps with minimal decoration (pyramid shaped śikhara) with a pinnacle usually consisting of a cupolic dome topped by a stūpikā or kalaśa type finial. Kadamba śikhara was adopted by later ruling dynasties of Karnataka (though not used universally) and also found its way into Telugu architecture. Some decoration may exist on a Kadamba śikhara, particularly “upwards spikes” on the tiers, and decoration on the cupolic dome. It may be considered a variant of Phamsaṇa type towers of Indian subcontinent temples.

→ Kadamba śikhara examples:

Bhuvaraha Narasimha temple at Halasi, Karnataka, India. It is one of the earliest examples of Kadamba style tower. The sanctum tower has a cupolic dome and urn shaped finial. (Built late 5th century CE, with additions in 9th-12th century CE) [Source: Halasi – Wikipedia]

A Śiva temple complex with a main temple and subsidiary temple, near a pond, in Ramteerth, Halasi, Karnataka, India. This complex is estimated to date back to same period as Bhuvaraha Narasimha temple, though is much less preserved. [Source: Ramteerth revisited – part 2]

Kadamba architecture can be considered the origin point of Karnāṭa architecture. It was developed under Kadambas of Banavasi (345 CE – 540 CE) and carried forward, along with their own innovations, by kingdoms and empires that succeeded them. Kadamba dynasty was established by Mayūra (r. ~345-365 CE) coinciding with the weakening of Pallava rule in the region by Samudragupta. The capital was established at Banavasi (near Sirsi in Uttara Kannada district, Karnataka, India). Kadambas were overthrown by their then feudatories Vatapi Cālukyas, in c.540 CE. Thereafter Kadambas became Vatapi Cālukya feudatories. The various Kadamba branches, thereafter, existed only as feudatories of more powerful polities.

Kadamba dynasty’s most significant contribution was the development of Kadamba śikhara — tower rising in steps with minimal decoration (pyramid shaped śikhara) with a pinnacle usually consisting of a cupolic dome topped by a stūpikā or kalaśa type finial. Kadamba śikhara was adopted by later ruling dynasties of Karnataka (though not used universally) and also found its way into Telugu architecture. Some decoration may exist on a Kadamba śikhara, particularly “upwards spikes” on the tiers, and decoration on the cupolic dome.

→ Kadamba empire (500 CE) [Source: Kadamba empire – Wikipedia]

The earliest known temple constructed by Kadambas i.e. Pranaveshvara temple at Talagunda lacks any superstructure, and may not have had one in the first place. Many other temples do have a Kadamba śikhara eg. Bhuvaraha Narasimha temple at Halasi and Madhukeshwara temple at Banavasi.

→ Pranaveshvara temple at Talagunda in Shikaripura taluk of Shivamogga district, Karnataka, India. This temple lacks any tower, but is among the earliest known Kadamba temple, dating to late 4th century CE. There is a Halegannada inscription slab next to it. [Source: Pranavesvara Temple and Inscribed Pillar, Talagunda]

1. View of the temple and inscription slab besides it.

2. Doorframe of the entrance is in the form of a decorative Tōraṇa-type gateway consisting of decorative columns and architrave. The top of the entrance has a Gaja-Lakṣmī carving [Source: Images from https://karnatakatravel.blogspot.com/2012/01/pranavesvara-temple-and-inscribed.html]

3. The ceiling decoration indicates that such decoration has been in existence in Karnāṭa temples at least since then

4. Datable to 5th century CE on box-headed Kadamba characters, the inscribed stone pillar in front of Pranavesvara Temple records that a tank was excavated by king Kakusthavarman (r. 405-430 CE) for the use of the temple. It is a fluted pillar, indicating direct or indirect influence from Hellenic architecture.

→ Bhuvaraha Narasimha temple at Halasi, Karnataka, India. It is one of the earliest examples of Kadamba style tower.

1. The sanctum tower has a cupolic dome and urn shaped finial. It has the regular plan adopted by Kadambas — a Kadamba śikhara vimāna, and an attached hall. (Built late 5th century CE, with additions in 9th-12th century CE) [Source: Halasi – Wikipedia]

2. Front view of the temple; the entrances are on the either sides of the attached hall [Source: Sri Bhuvaraha Narasimha Temple, Halasi – Temples of Karnataka ]

→ A Śiva temple complex with a main temple and subsidiary temple, near a pond, in Ramteerth, Halasi, Karnataka, India. This complex is estimated to date back to same period as Bhuvaraha Narasimha temple, though is much less preserved. [Source: Ramteerth revisited – part 2]

6th century CE – 8th century CE

Vatapi Cālukyas (543 CE – 753 CE)

Navasarika Cālukyas (7th century CE – 8th century CE)

Vatapi Cālukyas overthrew both Kadambas in Karnāṭa region and Vinukoṇḍas in Telugu region; the control over Telugu region lasted only for a short while though, with feudatory Viṣṇuvardhana declaring his independence and establishing Vengi Cālukya dynasty. Navasarika Cālukyas, a branch of Vatapi Cālukyas served as their vassals in parts of Maharashtra and Gujarat. Vatapi Cālukya reign came to end when their feudatories Rāṣṭrakūṭas led by Dantidurga overthrew them.

Vatapi Cālukyas adopted Kadamba śikhara in many of their temples, but did a lot of innovations themselves. Many of their temples don’t seem to belong to any particular style. Their architecture style originated in Aihole, and was perfected in their capital Badami (Vatapi) and Pattadakal, all lying in modern-day Karnataka. Alampur Navabrahma Temple Group (in Alampur, Telangana, India) was also constructed under Vatapi Cālukyas.

In ~7th century CE, Śukanāsa motif was developed from Candraśālā motif, and was adopted by Vatapi Cālukyas, probably starting with Parvati temple on Kraunchagiri. Vatapi Cālukyas also adopted the Candraśālā motif itself.

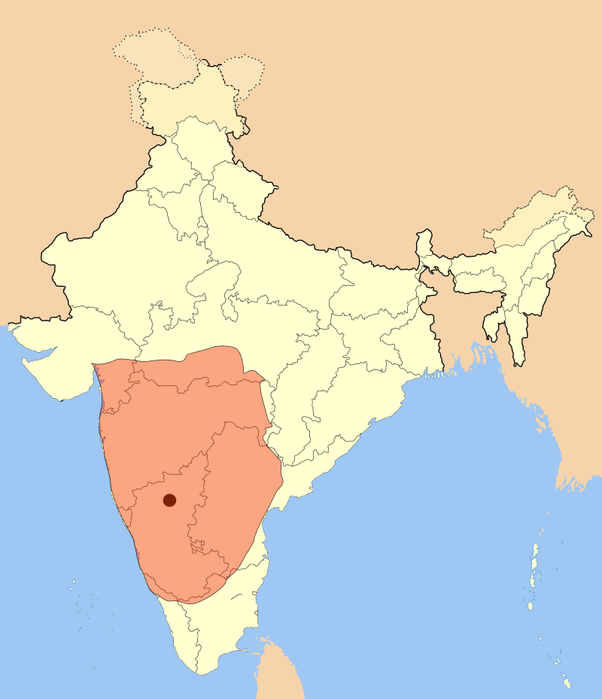

→ Extent of Vatapi Cālukya Empire, 636 CE, 740 CE — the capital Vatapi being the dark dot [Source: File:Badami-chalukya-empire-map.svg – Wikipedia]

General architectural features:

Material — the primary material used in constructing free-standing temples was sandstone, while rock-cut temples simply used the material of the hill they were carved in.

Superstructures — several types of superstructures can be found, but main following types exist:

Curvilinear (Latina) superstructure, topped by an āmalaka. The āmalakas are usually globular or slightly flattened.

Stepped-square superstructure topped by āmalakas similar as decribed above

Stepped-square superstructure with cupolic dome top

Floor-plan — with notable exception of the apsidal Durga Temple, most free-standing temples have rectangular floorplan. They may or may not have circumambulation paths integrated with them.

Entrances to temples —

Cave temples have a single entrance, that may or may not have door-guardians.

Free-standing temples can have one or multiple entrances.

The later temples may feature decorative mini-shrines of both Nāgara and Drāviḍa styles, called aediculae.

Aihole also referred to as Aivalli, Ahivolal or Aryapura, is a historic site of ancient and medieval era monuments in Bagalkot district, Karnataka, India. The site contains the earliest works of Vatapi Cālukyas, including those that have been estimated to date to 5th century CE during their Kadamba feudatory period. Temples at the site show a high degree of experimentation, as would be seen later. Temples were built at this site in 5th-12th centuries CE; the temples after 8th century were mostly added by Kalyani Cālukyas. Evidence of wooden and brick temples dating to 4th-century CE have also been unearthed. Temples at Aihole mainly feature own Cālukyan experimentation, Kadamba architecture influence and Nagara architecture influence.

According to Evolution of Temple Architecture – Aihole-Badami- Pattadakal (UNESCO), the regional artisans and architects of Aihole region created prototypes of 16 types of free-standing temples and 4 types of rock-cut temples.

Aihole temples experimented with two layouts: sāndhara (with circumambulatory path) and nirandhara (without circumambulatory path). The layout typically followed squares and rectangles (fused squares), but the Aihole artists also tried out prototypes of an apsidal layout as in Durga Temple.

In terms of towers above the sanctum, they explored several superstructures, including but not limited to:

Stepped square

Stepped square with āmalaka+kalaśa pinnacle

Stepped square with cupolic dome pinnacle (as commonly seen with Drāviḍa architecture)

Curvilinear towers with āmalaka+kalaśa pinnacle (as commonly seen with Nagara architecture)

Kadamba style superstructure

Muṇḍamāla (garland with shaved head) : temple without superstructure

→ Examples if temples in Aihole:

1. Śiva Temple (Lad Khan temple) is dated variously between 5th-8th century CE. It is one of the earliest temples at the site. The topmost structure in square in plan, while lower level and attached porch have rectangular plan.

1a. Side view of the temple showing stone beams mimicking logs, perforated stone windows[Source: File:Le temple de Ladkhan (Aihole, Inde) (14382588182).jpg – Wikimedia Commons]

1b. Front view of the temple [Source: File:Lad NKAD90.JPG – Wikimedia Commons]

2. Gaudargudi Temple is built along the lines of the above mentioned Śiva Temple, but more open from all sides. According to George Michell, the temple is older than the Śiva temple. It too has log-shaped stones, where its timber like form is integrated to serve its structural function.

Front view [Source: File:Le temple Gaudara Gudi (Aihole, Inde) (14383019304).jpg – Wikimedia Commons]

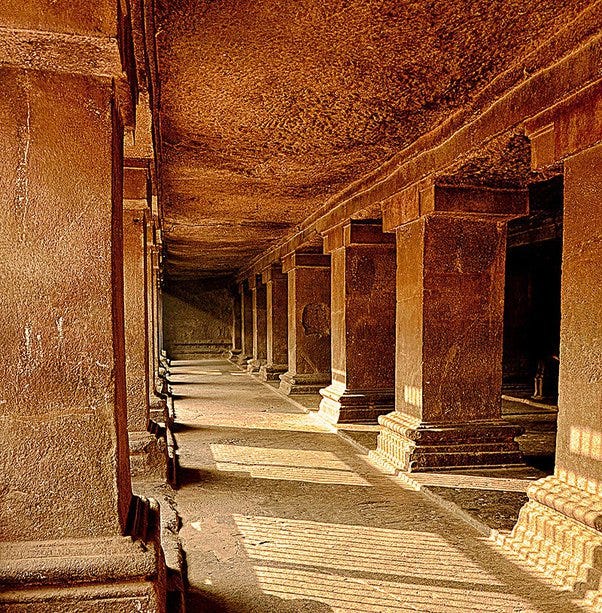

3. Durga temple (actually a Śiva Temple) dated between 5th – late-8th century CE. It follows a rare apsidal floorplan, and features numerous carvings. The most original feature of the temple is a peristyle delimiting an ambulatory around the temple itself and whose walls are covered with sculptures of different gods or goddesses. The rounded ends at the rear or sanctuary end include a total of three layers: the wall of the sanctuary itself, the main temple wall beyond a passageway running behind this, and a pteroma or ambulatory as an open loggia with pillars, running all round the building.

3a. Rear view of the temple showing the apsidal end. The tower once had an āmalaka pinnacle which now lies nearby on the ground [Source: File:Group of Temples Aihole (20169954306).jpg – Wikimedia Commons]

3b. Temple’s front view with numerous carvings visible [Source: File:DurgaTempleAihole.JPG – Wikimedia Commons]

3c. Ambulatory inside the temple [Source: File:Profile of mantapa outer wall in Durga temple in Aihole.JPG – Wikimedia Commons]

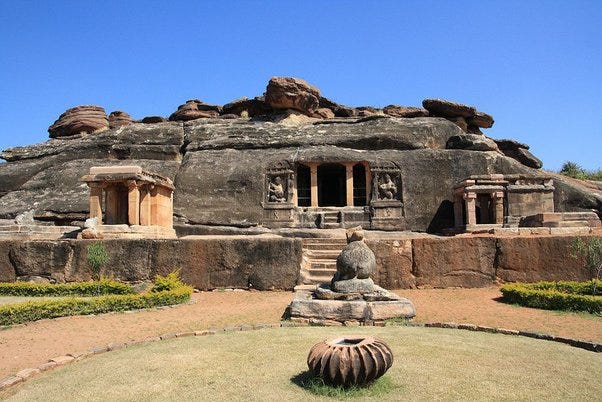

4. Ravanaphadi is among the few cave temples at the site, and dates to 6th century CE. [Source: File:Phadi NKAD81.JPG – Wikimedia Commons]

5. A 2-storied Buddhist cave dated to 6th century CE, carved in Meguti hill [Source: File:Two storeyed Buddhist Chaithya (Hall) and cave at Meguti hill, Aihole.JPG – Wikimedia Commons]

6. Meguti hill Jaina temple dating to 6th-8th century CE. It sits on a raised platform, and has a pillared square main hall which enters into a narrower square vestibule divided into two compartments at different levels. [Source: File:HBPA N 930 Meguti Jain temple Aihole (cropped).jpg – Wikimedia Commons]

7. Suryanarayana Gudi dated to 7th-8th century CE. It had a Rēkhā Prāsāda type tower (presently fallen). The remains include the remaining section of vimāna and the attached porch. [Source: Durga Temple Complex, Aihole]

8. Chakragudi has its Rēkhā Prāsāda type tower preserved. It is dated to 7th-8th century CE. The temple shows signs of later addition of a hall, whose style suggests 9th-century Rāṣṭrakūṭa extension.

8a. Front view of the temple [Source: Durga Temple Complex, Aihole]

8b. The temple can be seen having a Śukanāsa; Śukanāsa was developed in 6th-7th century CE and adopted widely in Indian subcontinent. [Source: templesofkarnataka.com]

9. Sūrya temple (carpenter’s house) dating to 8th century CE. It features a Kadamba śikhara though the topmost part seems to have fallen. [Source: karnatakatravel.blogspot.com/2013/11/durga-temple-complex-aihole.html]

10. Hucchimalli Gudi Temple Complex consists of 3 temples, with the largest one Hucchimalli Gudi having a Rēkhā Prāsāda type tower similar to Chakragudi. A smaller temple besides seems to have had either Kadamba type or Phamsaṇa type tower. The third structure facing opposite to the main temple is clearly another experimentation where the temple is constructed in an elongated shape. A small broken idol of Nandī sits facing the temple. [Source: Group of Monuments at Aihole – Viki Pandit]

11. Mallikarjuna temple complex features five monuments. The main temple in this complex is dated to ~700 CE and features a stepped pyramidal tower. [Source: File:Mallikarjuna temple complex at Aihole.jpg – Wikimedia Commons]

12. Kuntigudi group collonade. This group is variously dated to 6th-8th century CE [Source: File:Kunti gudi temples group Aihole Karnataka.jpg – Wikimedia Commons]

Vatapi (present Badami in the Bagalkot district of Karnataka, India) was the capital of Vatapi Cālukyas, and was established soon after they became independent. Vatapi was founded by Pulakeśin I (r. c. 540–567 CE) who also founded Cālukya dynasty.

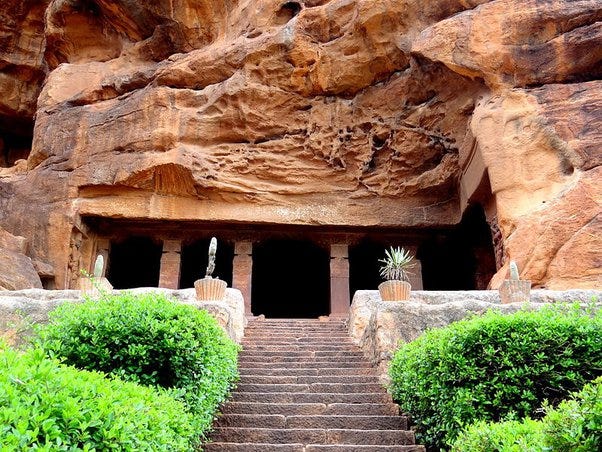

The main Vatapi Cālukya monuments in Vatapi are Badami Caves (6th-8th century CE) and Bhutanath temple group. In case of Bhutanath temple group, Bhutanath temple (temple No1) had its vimāna and inner hall constructed under Vatapi Cālukyas, with rest of structures under Kalyani Cālukyas.

→ Badami caves consist of multiple caves: 4 major numbered caves and numerous small un-numbered caves [Source: Badami cave temples – Wikipedia]

1. Cave 1 entrance

2. Cave 2 showing the iconography of Bhū-Varāha and Trivikrama

3. Cave 3 showing Viṣṇu seated on the serpent Ananta

4. Cave 4 showing Pārśva

→ Badami Shivalaya Group is a group of 3 Śiva temples in Badami constructed 7th-8th century CE.

1. Lower Shivalaya [Source: Hiking to the Shivalayas of Badami – Rare Photos by Viki Pandit]

2. Upper Shivalaya (Built 600–625 CE) [Source: Hiking to the Shivalayas of Badami – Rare Photos by Viki Pandit]

3. Malegitti temple (Built 625–675 CE) [Source: File:Badami, Malegitti-Shivalaya-Tempel 3 (1999).jpg – Wikimedia Commons]

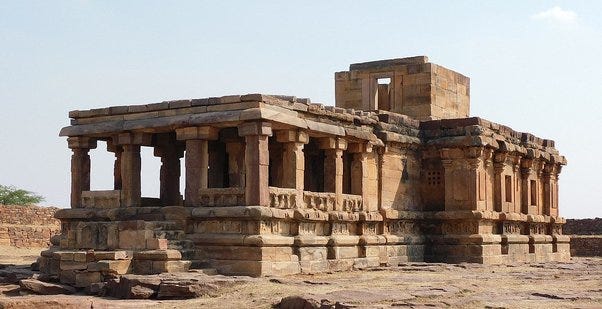

Pattadakal (place of coronation) is a complex of 7th and 8th century CE temples in Bagalkot district, Karnataka, India. Although the area was not a capital region, nor in proximity to one, numerous sources such as inscriptions, contemporaneous texts and the architectural style indicate that, from 9th-12th centuries CE, new Sanatanist, Jaina and Buddhist temples and monasteries continued to be built in Pattadakal region. Historian George Michell attributes this to the presence of a substantial population and its burgeoning wealth.

Temples at Pattadakal show a higher influence of Drāviḍa architecture, as well as the continuing influence of Nagara architecture and Kadamba architecture.

1. Jambulingeshwara temple estimated to have been complete between mid 7th and early 8th century CE. It features a Rēkhā Prāsāda type tower, and a relatively large Śukanāsa; the pinnacle however has fallen [Source: Pattadakal – Wikipedia]

2. Sangameshwara temple a.k.a. Vijayeshvara temple. Inscriptions at the temple, and other evidence, date it to between 720-733 CE. The death of its patron king, Vijayāditya, in 734 CE resulted in the temple being left unfinished, although work continued intermittently in later centuries. The temple has a square layout, with an east facing sanctum. The sanctum, surrounded by a covered circumambulatory pat lit by three carved windows. Inside the sanctum is a Śiva-Liṅga. In front of the sanctum is a vestibule that is flanked on each side by smaller shrines. These shrines once contained carvings of Gaṇēśa and Durgā, but the carvings have since gone missing. Further east of the hall is a seated Nandī. Past the vestibule is a hall within which are sixteen massive pillars set in groups of four, which may have been added after construction of the temple was completed. [Source: Pattadakal – Wikipedia]

3. Galaganatha temple estimated to have been completed sometime between late-7th and mid-8th century CE. It features a relatively well-preserved Rēkhā Prāsāda type tower. [Source: Pattadakal – Wikipedia]

4. Mallikarjuna temple, also called the Trailokeshwara Maha Saila Prasada in a local inscription, is a mid 8th-century CE Śiva temple sponsored by queen Trailōkyamahādēvī. This temple shows a high degree of Drāviḍa style influence, and might have had a towering gateway as well. [Source: Pattadakal – Wikipedia]

5. Virupaksha temple is the largest and most sophisticated of the monuments at Pattadakal. In inscriptions, it is referred to as “Shri Lokeshvara Mahasila Prasada”, after its sponsor queen Lōkamahādēvī, and is dated to about 740 CE. This temple also shows a high degree of Drāviḍa style influence. The tower above the sanctum is a three-storey pyramidal structure, with each storey bearing motifs that reflect those in the sanctum below. However, for clarity of composition, the artisans had simplified the themes in the pilastered projections and intricate carvings. [Source: Pattadakal – Wikipedia]

6. Papanatha temple has been dated towards the end of the Vatapi Cālukya rule period, approximately mid 8th-century CE. Its architectural and sculptural details do show a consistent and unified theme, indicative of a plan. The temple is long, incorporating two interconnected halls, one with 16 pillars and another with 4 pillars. The decorations, parapets and some parts of the layout are Drāviḍa in style, while the tower and pilastered niches are of the Nagara style. [Source: Pattadakal – Wikipedia]

Mahakuta group of temples in Mahakuta village, Bagalkot district, Karnataka, India was constructed in 6th-7th century CE. The dating of the temples is based on the style of architecture which is similar to that of the temples in nearby Aihole and the information in two notable inscriptions in the complex: the Mahakuta Pillar inscription dated between 595–602 CE (written in Saṁskr̥ta language and Kannada script); and an inscription of Vinapoti, a concubine of king Vijayāditya, dated between 696–733 CE and written in Kannada language and script.

→ Mahakuta Temples

1. Viṣṇu temple with nagara superstructure (left) and a temple with Phamsaṇa superstructure (right) [Source: File:Mahakuta group of temples2 at Mahakuta.jpg – Wikimedia Commons]

2. Sangameshvara temple with Nagara superstructure at Mahakuta [Source: File:Mahakuta group of temples3 at Mahakuta.jpg – Wikimedia Commons]

3. Mallikarjuna temple (at rear), a temple with Drāviḍa style tower at Mahakuta [Source: File:Mahakuta group of temples1 at Mahakuta.jpg – Wikimedia Commons]

Alampur Navabrahma Temples at Alampur, Jogulamba Gadwal district, Telangana, India is a group of 9 temples dating to 7th-9th century CE having mainly Nāgara architecture influence.

→ Source: Alampur Navabrahma Temples – Wikipedia]

1. Kumara Brahma is probably the earliest temple built, and like others stands on a platform. The outer walls provide a perforated screen to let natural light come into the circumambulation path. The pillars and beams in the ceiling are all carved with miniature figures and peacock motifs.

2. Bala Brahma temple is likely the second oldest here, likely completed by ~650 CE. It has Saṁskr̥ta inscriptions in early Telugu script, one of which can be dated to 702 CE.

2a. Nagara style śikhara of the temple

2b. Outer covered hall

3. Swarga Brahma temple was built during 681-696 CE. An inscription found in the temple states that Lōkāditya built it in the honour of the queen. [Source: Alampur Navabrahma Temples – Wikipedia]

3a. Front view showing the entrance porch, aediculae, and Vimāna with Śukanāsa

3b. Pillars inside the hall

Parvati Temple at Krauncha Giri, Bellary district, Karnataka, India constructed under Vatapi Cālukyas is believed to be the earliest Karnāṭa style temple to exhibit śukanāsa motif.

→ Parvati Temple at Krauncha Giri, Bellary district, Karnataka, India. The temple has Kadamba śikhara and śukanāsa (developed from Candraśālā motif) on the sanctum tower — the temple is believed to be the earliest Karnāṭa style temple to exhibit such decoration [Source: File:Parvati temple at Krauncha Giri near Sandur, Ballary district.jpg – Wikipedia]

7th century CE – 10th century CE

Manyakheta Rāṣṭrakūṭas (753 CE – 982 CE)

Vemulwada Cālukyas (7th century CE – 10th century CE)

Karnāṭa Gaṅgas (r. 4th century CE – 11th century CE)

This long period saw the rise and fall of multiple empires and kingdoms, and consequent development of Vesara architecture. During this period, Cōḻas exerted large influence on Telugu region and Kaḷiṅga region via the matrimonial relationships with Vengi Cālukyas and Kaḷiṅga Gaṅgas — this led to rise of Cālukya Cōḻas in Tamil & Telugu regions and rise of Cōṛagaṅgas in Kaḷiṅga region.

Karnāṭa region based empires continued to exert influence over parts of Telugu region outside control of Vengi Cālukyas, via their own feudatories. Such feudatories included both Karnāṭa origin dynasties (like Vemulwada Cālukyas) and Telugu origin dynasties (like initial rule of Kākatīyas under Kalyani Cālukyas)

Rāṣṭrakūṭas (753–982 CE) were feudatories of Vatapi Cālukya, and once independent, created one of the largest empires in India with their capital at Manyakheta (present-day Malkhed in Karnataka, India). Rāṣṭrakūṭa architecture, a sub-style of Karnāṭa architecture, developed during this period.

Karnāṭa Gaṅgas (r. 4th–11th century CE) ruled parts of southern Karnataka. They were initially feudatories of Pallavas, becoming independent from c. 350 CE – 550 CE, later becoming feudatories of Vatapi Cālukyas and then Rāṣṭrakūṭas. Most of Karnāṭa Gaṅga temples (and that of their subordinates) were built in 9th century CE – 10th century CE when they were Rāṣṭrakūṭa feudatories.

Rāṣṭrakūṭa architecture influenced Telugu architecture through their feudatories Vemulavada Cālukyas (r. 7th–10th century CE), who created Rāṣṭrakūṭa architecture influenced temples in Telugu region.

Rāṣṭrakūṭa empire under the reign of Khottiga (967 CE – 972 CE) was dealt a significant blow by Harṣa Sīyaka Paramāra (948 CE – 972 CE) who attacked the empire and plundered the capital Manyakheta. Following this Tailapa Cālukya II declared independence, starting Kalyani Cālukya dynasty, and ending Rāṣṭrakūṭa reign. Vemulavada Cālukyas seem to have been conquered by Kalyani Cālukyas in 970s CE itself, bringing an end to Rāṣṭrakūṭa influence in Telugu region.

→ Extent of Rāṣṭrakūṭa Empire, 800 CE, 915 CE [Source: File:Indian Rashtrakuta Empire map.svg – Wikipedia]

General architectural features:

Their style incorporated stellate projections, that were later used by both Kalyani Cālukyas and Hoysaḷas.

The sanctum towers were usually of Drāviḍa style, although they were taller than the gateways of the temples (if any). They were also more steep and shorter than pure Drāviḍa towers

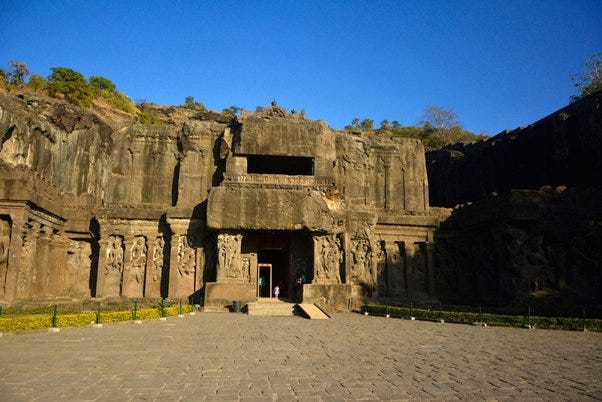

Temple construction by Rāṣṭrakūṭas seems to have started with the cave temples at Ellora (Maharashtra, India), moving to free-standing temples in Karnataka, India. Among the earlier Rāṣṭrakūṭa works are the cave temples of Ellora and Pataleshwar Cave (Pune, Maharashtra, India). Some caves of Elephanta Caves (Mumbai, Maharashtra, India) are also suggested to be of Rāṣṭrakūṭa period. The last inscription of Ajanta Caves (Aurangabad district, Maharashtra, India) is at Cave 26 and belongs to Rāṣṭrakūṭas, dateable to late 7th or early 8th century CE.

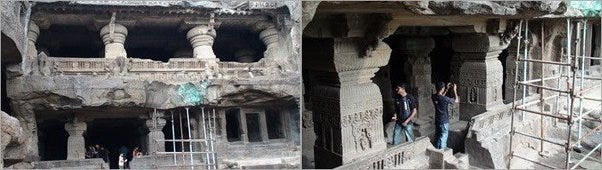

Ellora was already a site of numerous cave temple before Rāṣṭrakūṭa empire came into existence. The earliest Rāṣṭrakūṭa inscription at the site actually predates the empire’s founding: A copper plate inscription dated to 742 CE was donated here by Dantidurga emphasizing the religious importance of Ellora and expressing his quest for establishing the new dynasty of Rāṣṭrakūṭas. Rāṣṭrakūṭa era caves at the site include Caves 15–16, and initial excavations of Caves 30–33.

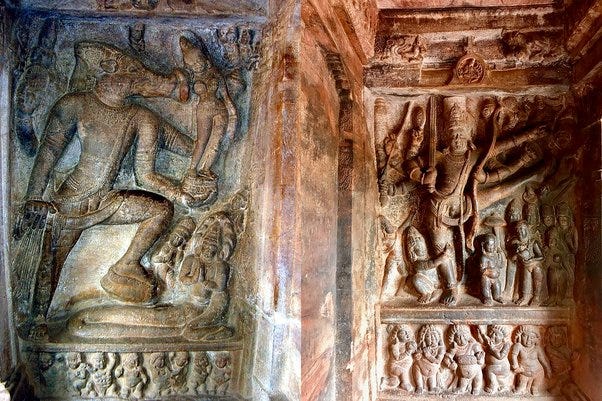

→ Ellora Caves:

1. Dashavatara Cave (Cave 15) has an inscription on the back wall of the monolithic Nandī hall recording a donation by Dantidurga; the inscription also established the age of the temple. [Source: The Architecture of Ellora Caves | Sahapedia]

1a. Pillared hall at upper floor

1b. Carving on the wall of upper floor

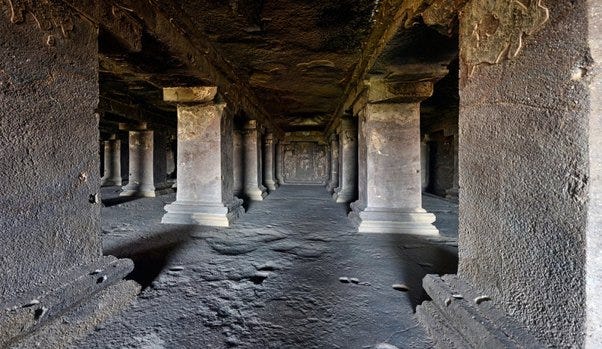

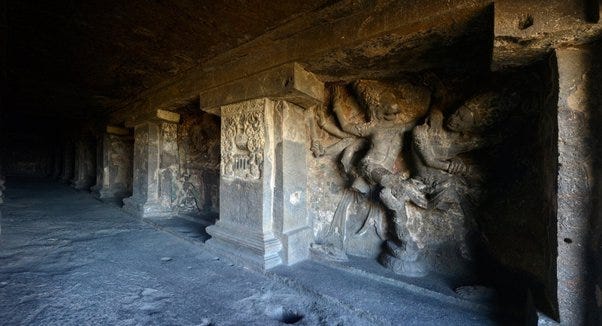

2. Kailasa Temple (Cave 16) is the largest temple complex at the site, and one of the largest monolithic rock-cut temple complexes in the world. It was constructed mainly or completely under Kr̥ṣṇa I. The architecture styles employed at the complex suggest contributions of Cālukyan, Pallavan and Western Indian artisans.

2a. Front view showing the gateway and screen carvings [Source: The Architecture of Ellora Caves | Sahapedia]

2b. Inner courtyard [Source: The Architecture of Ellora Caves | Sahapedia]

2c. Shrines of river deities [Source: The Architecture of Ellora Caves | Sahapedia]

2d. View showing the main vimāna and attached hall [Source: File:Ellora cave16 001.jpg – Wikimedia Commons]

3. Chhota Kailasa (Cave 30) is a small-scale, incomplete replica of Kailasa Temple Complex, with a temple standing freely in the middle of a court. This monolith consists of a columned mandapa entered through a porch; balcony seating is adorned with friezes of pots, pilasters, and elephants. [Source: The Architecture of Ellora Caves | Sahapedia]

4. Indra Sabha (Cave 32) consists of a simple gateway leading to an open court in the middle of which stands a monolithic shrine. This has a pyramidal superstructure capped with an octagonal roof. Miniature Jaina figures adorn the arched niches of the roof projections. A free-standing elephant and column are also positioned here.

4a. Front view [Source: The Architecture of Ellora Caves | Sahapedia]

4b. Sculptures inside [Source: The Architecture of Ellora Caves | Sahapedia]

4c. Indra Sabha’s vimāna’s upper portion [Source: File:Indra Sabha Ellora Temple Maharashtra India.jpg – Wikimedia Commons]

5. Jagannatha Sabha (Cave 33). The court of the cave is much smaller than that of Indra Sabha, and had contained some sculptures which are now destroyed. The hall has two heavy square pillars in front and four in the middle area. [Source: http://indiathatwas.com/2014/07/elloracave-33jagannatha-sabha-and-cave-34/]

→ Pataleshwar Cave Temple in Pune, Maharashtra, India is a temple made of basalt rock and dedicated to Śiva. The sanctum – a cube-shaped room ~3–4m on each side houses a liṅgam and there are two smaller cells on each side. In front of the cave is a circular Nandi hall, its umbrella shaped canopy supported by massive square pillars. The temple is dated to 8th century CE. [Source: Pataleshwar – Wikipedia]

1. Nandī hall

2. Internal Columns

Free standing temples contsructed directly under Rāṣṭrakūṭas include those at Pattadakal, Aihole and Kuknur in Karnataka, India. In Aihole, Chakragudi temple was expanded, and some temples of Jyotirlinga group of monuments were built. Other free-standing temples built during this period include Padmabbarasi Basadi (both in Naregal in Gadag district, Karnataka, India; 10th century CE).

→ Navalinga Temple cluster in Kuknur was built in 9th century CE, either under Amōghavarṣa or his son Kr̥ṣṇa II. It consists of similar standalone-vimāna type temples arranged without any order [Source: File:Kuknur Navalinga temples.JPG – Wikimedia Commons]

→ Jain Narayan Temple in Pattadakal, constructed under Kr̥ṣṇa II in 9th century CE. The temple can be seen having a somewhat similar plan to Kailasa Temple of Ellora, though on a smaller scale. [Source: File:Jain Narayana temple at Pattadakal.JPG – Wikimedia Commons]

→ Rameshvara Temple in Kubatur, Sorab taluk, Shimoga district, Karnataka, India [Source: Kubatur – The Forgotten City of Chandrahasa]

→ Triyambakeshvara Temple Group (10th-11th century CE) in Aihole bridges the gap between Rāṣṭrakūṭa and Kalyani Cālukya Architecture styles. Rachigudi temple (below) features a sloping stone roof and its outside wall has floral and other carvings. [Source: File:Rachigudi Temple, Aihole (1).JPG – Wikipedia]

Vemulwada Cālukya architecture was highly influenced from Rāṣṭrakūṭa architecture, but still shows many native features/influences. In particular, Vemulwada Cālukya temples have vimāna with a cavity near the place where the roof of attached hall meets the vimāna.

Neelakanteshwara Temple in Nizamabad, Nizamabad district, Telangana has its hall following the staggered square plan indicating that such floor-plan was known at least since this period. {staggered square floor-plan is quite popular with Karnāṭa and Māru-Gurjara architecture}

→ Bhimeshwara temple in Vemulawada — features a curvilinear ridged pyramidal śikhara, without a Śukanāsa but a cavity in its place. (Built 840–880 CE) [Source: Prashhantham (ప్రశాంతం)’s answer to What are the various temple architectural styles in Telangana?]

→ Neelakanteshwara Temple in Nizamabad, Nizamabad district, Telangana, India — the cavity is itself surrounded by Śukanāsa motif. The vimāna has a Bhūmija śikhara, with each face bifurcated by a vertical “strip”. The attached hall follows a staggered square plan. [Source: Neelakanteshwara Temple (Kanteshwar Temple)]

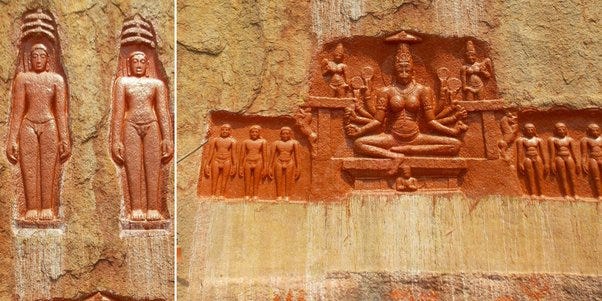

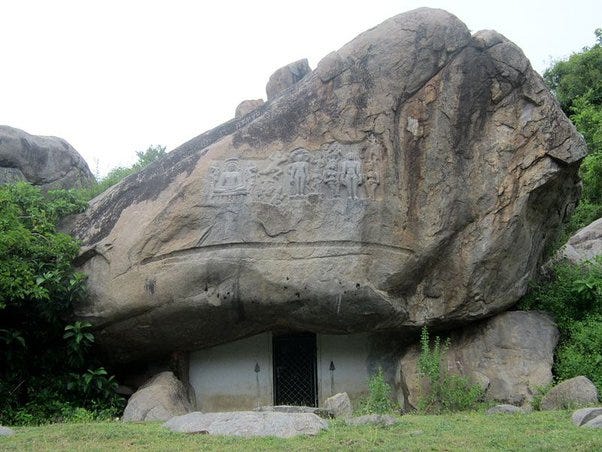

→ Bommalagutta in Karimnagar district, Telangana, India — features inscriptions and Jaina icon carvings dating to 10th century CE [Source: Bommalammagutta (with inscription)]

Karnāṭa Gaṅga architecture combined their own features along with Vatapi Cālukya and Pallava architecture. These features are also found in structures built by their subordinates, Banas and Nolambas. Karnāṭa Gaṅga dynasty temples include both rock-cut and free-standing structures.

Most of Karnāṭa Gaṅga temples (and that of their subordinates) were built in 9th century CE – 10th century CE.

→ Core Karnāṭa Gaṅga Territory [Source: File:Western-ganga-empire-map.svg – Wikimedia Commons]

Gaṅga dynasty temple pillars with a lion at the base and a circular shaft of the pillar on its head, the stepped vimāna of the temple with horizontal mouldings, and square pillars were features inherited from Pallavas. The experiments with staggered-sqaure plan seems to be from Vatapi Cālukyas and/or Rāṣṭrakūṭas. Some Gaṅga dynasty temples also have multiple vimānas connected by a single hall to form a temple {a feature seen mainly with Kalyani Cālukyas and Hoysaḷas discussed later}.

Panchakuta Basadi in Kambadahalli village has one of the earliest, if not the earliest known examples of dvikūṭa (double vimāna) and trikūṭa (triple vimāna) type temples.

→ Panchakuta Basadi (5-house temple) at Kambadahalli, Mandya district, Karnataka state, India — the complex consists of a trikūṭa temple and a slightly later dvikūṭa temple, hence its name. All the vimānas are built in typical Drāviḍa style. [Source: File:Panchakuta Basadi (10th century AD) at Kambadahalli.JPG – Wikimedia Commons]

→ Image from Vallimalai Jain cave in Vallimalai village in Katpadi taluk of Vellore district, Tamil Nadu, India (9th century CE). [Source: Vallimalai Jain caves – Wikipedia]

→ Mahavir Cave Temple in Seeyamangalam, Vandavasi taluk, Tiruvannamalai district, Tamil Nadu, India (9th century CE). [Source: Seeyamangalam – Wikipedia]

→ Kalleshvara Temple in Aralaguppe village in Tiptur taluk of Tumkur district, Karnataka, India — constructed by Nolambas in 10th century CE, this temple has a stepped pyramidal steep superstructure topped a quasi-cupolic dome. [Source: Kalleshvara Temple, Aralaguppe – Wikipedia]

→ Chavundaraya Basadi on Chandragiri, Shravanabelagola, Hassan district, Karnataka, India (10th century CE) — mostly incorporating Pallava style architecture features [Source: Chavundaraya Basadi – Wikipedia]

→ Panorama of Chandragiri showing different types of Jain Temples (basadi) constructed on the hill by Gaṅga dynasty [Source: File:Panorama of Chandragiri Temple Complex, Shravanabelagola, Karnataka, India..jpg]

→ The monolithic Gommateshwar Bahubali Statue on Chandragiri — this statues formed the basis of at least 4 other monolithic statues carved later in Karnataka. [Sources: File:Shravanabelagola Bahubali wideframe.jpg]

→ Panchakuta Basadi (5-vimāna temple) in Kambadahalli village in Mandya district of Karnataka, India — the complex actually consists of 2 temples: an earlier trikūṭa (triple vimāna) temple and a later dvikūṭa (double vimāna) temple. (Built 8th-10th century CE)

1. Full view of the complex [Source: Kambadahalli – The Pillar, the Namesake]

2. Open hall [Source: File:A mantapa (hall) in Panchakuta Basadi with Jain sculptures at Kambadahalli.JPG – Wikimedia Commons]

3. Closed hall [Source: File:Ornate pillars in a mantapa of the Panchakuta Basadi at Kambadahalli.JPG – Wikimedia Commons]

Śilāhāras originated as Rāṣṭrakūṭa feudatories and later became independent. They ruled parts of Mumbai and Southern Konkan in present-day Maharashtra. They established 3 different polities: South Konkan Śilāhāras (765–1020 CE), North Konkan Śilāhāras (800–1265 CE) and Kolhapur Śilāhāras (940–1212 CE). They were later overthrown by Sēuṇas.

The original structures of Walkeshwar Temple, Babulnath Temple and Kopineshwar Temple were constructed during their reign.

→ Ambarnath Shiv Temple at Ambarnath near Mumbai, in Maharashtra, India. It shows clear Karnāṭa architecture influence in form of staggered square plan, Karnāṭa style entrance porches of the main hall and other features. (Built 1060 CE) [Source: File:Shiv Mandir, Ambernath.jpg – Wikimedia Commons]

→ Kopeshwar Temple at Khidrapur, Kolhapur district, Maharashtra, India. The temple features an uncommon faceted, almost conical tower and its hall has a deliberate opening in the roof — these feature uncommon in Karnāṭa architecture. (Built 1109-1178 CE) [Source: Kopeshwar Temple – Wikipedia]

10th century CE – 12th century CE

Kalyani Cālukyas (973 CE – 1189 CE)

Hangal Kadambas (10th century CE – 14th century CE)

Goa Kadambas (960 CE – 1310 CE)

Lata Cālukyas (~970 CE – 1070 CE)

Kanduru Cōḻas (1080 CE – 1260 CE)

Nellore Cōḻas

Kalyani Cālukya Architecture was developed during Kalyani Cālukya period (973 CE – 1189 CE). They became independent of Rāṣṭrakūṭa empire under Tailapa II in 957 CE who later founded the capital in Manyakheta itself. Vemulavada Cālukyas seem to have been conquered by Kalyani Cālukyas in 970s itself, bringing an end to Rāṣṭrakūṭa influence in Telugu region. Their capital was moved to Kalyani (present-day Basavakalyan) in 1042 CE under Sōmēśvara I. They also established a second capital in Kolanupaka (present-day Telangana, India) leading to multiple temples being built in Telugu region by them and their feudatories, particularly Kanduru Cōḻas.

Initially, other major ruling families of Deccan: Dvarasamudra Hoysaḷas, Devagiri Sēuṇas, Oragallu Kākatīyas, Kanduru Cōḻas and Kalyani Kalacuris were subordinates of Kalyani Cālukyas and gained their independence only when the power of Kalyani Cālukyas waned during later half of 12th century CE. Lata Cālukyas (~970 CE – 1070 CE) ruled as Kalyani Cālukya feudatories in Lata region of Gujarat, India. Kalyani Cālukya Architecture was carried forward partly by Devagiri Sēuṇas, who constructed a few temples based on those of their former overlords.

Hoysaḷas under Vīra Ballāḷa II (r. 1173 CE – 1220 CE) defeated Kalyani Cālukyas on several occasions gaining large parts of their territories and becoming independent. The dynasty was brought to downfall by Seuṇa rulers who drove Sōmēśvara IV into exile in Banavasi 1189 CE.

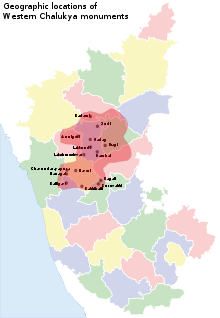

→ Core area of Western Cālukya architectural activity in modern Karnataka [Source: File:Western Chalukya Monuments.svg – Wikipedia]

General architectural features:

These temples are smaller than Vatapi Cālukya temples. The pillars of the halls are monolithic shafts, which meant that the size of stones that could be found decided the height of the halls. The height of the temple is also constrained by the weight of the superstructure on the walls and, since the architects did not use mortar, by the use of dry masonry and bonding stones without clamps or cementing material.

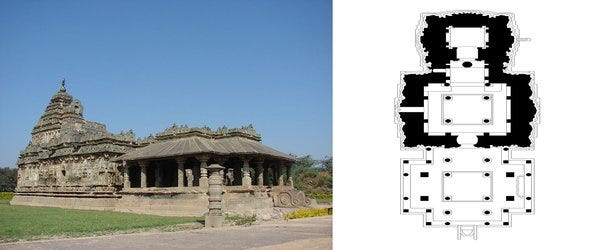

The temples fall into following broad categories:

single vimāna and hall, termed ēkakūṭa — the hall can have 3 entrances

2 vimānas sharing a common hall, termed dvikūṭa — the common hall usually has one or two entrances

3 vimānas sharing a common hall, termed trikūṭa (rare examples) — the common hall usually has one entrance

Many temples incorporate stellate (star-like) pattern in floor-plan and sanctum towers.

The towers are pyramid, with stories becoming shorter and with ornate carvings. The towers are mainly of Kadamba Śikhara and Bhūmija Śikhara style in case of square/rectangular layout. The top of the towers can have cupolic dome + urn pinnacle, notched disk + urn pinnacle or simply an urn finial; the first one is the most common.

Pillars were a major part of temples and were produced in 2 main types:

Pillars with alternate square blocks and a sculptured cylindrical section with a plain square-block base, which were more vigorous and stronger

Bell-shaped lathe-turned pillars made of soapstone.

While the earlier temples were built using sandstone, later temples were built using soapstone. The 1st temple to be built from this material was Amruteshwar Temple in Annigeri, Dharwad districtin 1050 CE which was the prototype for later, more articulated structures.

Decorative features —

The temples feature decorative mini-shrines of both Nagara and Drāviḍa styles, called aedicules.

The temples also regularly feature Kīrtimukha-Kuḍu motif, developed from Candraśālā motif in ~7th century CE.

Kalyani Cālukya Architecture evolved in two phases:

973 CE–1000 CE — During the first phase, temples were built in the Aihole-Banashankari-Mahakuta region (situated in the early Cālukya heartland) and Ron in Gadag district. A few provisional workshops built them in Sirval in Kalaburagi district and Gokak in Belgaum district — the structures at Ron bear similarities to the Rāṣṭrakūṭa temples in Kuknur in the Koppal district and Mudhol in the Bijapur district, evidence that the same workshops continued their activity under the new dynasty.

1000 CE–1189 CE — The latter phase reached its peak at Lakkundi (Lokigundi), a principal seat of the imperial court. From the mid-11th century CE, the artisans from the Lakkundi school moved south of Tungabhadra River. Thus the influence of the Lakkundi school can be seen in some of the temples of Davangere district, and in the temples at Hirehadagalli and Huvinahadgalli in Bellary district.

→ The temples in Sudi, Ron taluka, Gadag district, Karnataka, India represent the early phase of Kalyani Cālukya Architecture. These were constructed ~1000 CE. [Source: Sudi – Twin Temples of Karnataka]

1. Mallikarjuna Temple is a trikūṭa type temple

2. Jodu-kalasa Temple is a dvikūṭa type temple

From 11th century CE, newly incorporated features were either based on the traditional Drāviḍa architecture based plan of Vatapi Cālukyas {as found in Virupaksha and Mallikarjuna Temples at Pattadakal, Karnataka, India}, or were further elaborations of this articulation. The new features produced a closer juxtaposition of architectural components, visible as a more crowded decoration, as can be seen in Sudi Mallikarjuna Temple (in Gadag district, Karnataka, India) and Annigeri Amrtesvara Temple (in Dharwad district, Karnataka, India).

Also since 11th century CE, soapstone became the preferred material for temple construction. Soapstone is found in abundance in the regions of Haveri, Savanur, Byadgi, Motebennur and Hangal. The great archaic sandstone building blocks used by Vatapi Cālukyas were superseded with smaller blocks of soapstone and with smaller masonry.

→ Yellamma temple in Badami, Bagalkot district, Karnataka, India. (Built 11th century CE) [Source: File:Yellamma temple at Badami.jpg – Wikimedia Commons]

→ A few temples were still constructed using sandstone, but such temples became rare with time

Mallikarjuna Temple at Sudi in Gadag district, Karnataka, India (Built 1054 CE by governor princess of the region) [Source: ಸುತ್ತೋಣ ಬನ್ನಿ – Sutthona Banni]

Kalleshwara temple at Hire Hadagali in Bellary district, Karnataka, India (Built 1057 CE by Demarasa the prime minister of Sōmēśvara I) [Source: File:Kalleshvara temple (1057 AD) at Hire Hadagali.JPG – Wikimedia Commons]

→ Annigeri Amrtesvara Temple in Annigeri, Dharwad district, Karnataka, India. It was the first temple constructed in soapstone (Built ~1050 CE) [Source: Indian History and Architecture]

→ Sri Ramalingeswara Temple at Nandikandi, Medak, Telangana, India (Built 11th century CE) [Source: Sri Ramalingeswara Temple at Nandikandi | Star Shaped Temple in Medak, Telangana – Temples In India Info – Slokas, Mantras, Temples, Tourist Places]

→ Sri Lakshmi Chennakesava Swamy Temple Complex in Gangapuram Mahabubnagar, Telangana, India — complex of 5 temples built in 1042–1063 CE [Source: Sri Lakshmi Chennakesava Swamy Temple Gangapuram Mahabubnagar – Temples In India Info – Slokas, Mantras, Temples, Tourist Places]

In 12th century CE, new features were added to temples. The voluptuous carvings of the 11th century were replaced with a more severe chiselling. Mahadeva Temple in Itagi has the same architectural components as Annigeri Amrtesvara Temple. There are however differences in their articulation — the sala roof (roof under the finial of the superstructure) and the miniature towers on pilasters are chiseled instead of moulded. The difference between the two temples is the more rigid modelling and decoration found in many components of Mahadeva Temple.

→ Mahadeva Temple in Itagi, Yelburga Taluk, Koppal district, Karnataka state, India. (Built 1112 CE) [Source: File:Mahadeva Temple at Itagi in the Koppal district.JPG – Wikimedia Commons]

As developments progressed, Cālukyan builders modified the pure Drāviḍa tower by reducing the height of each stepped storey and multiplying their number. From base to top, the succeeding storeys get smaller in circumference and the topmost storey is capped with a crown holding the kalaśa finial. Each storey is so richly decorated that the original Drāviḍa character becomes almost invisible. The characteristically Nagara style stepped-diamond plan of projecting corners was adopted in temples built with an entirely Drāviḍa articulation. Four 12th century CE structures constructed according to this plan are extant: Basaveshwara Temple at Basavana Bagevadi, Ramesvara Temple at Devur and the temples at Ingleshwar and Yevur, all in the vicinity of Kalyani region.

→ L2R:

Basaveshwara Temple at Basavana Bagevadi in Vijayapura district, Karnataka, India. [Source: Basaveshwara Devalaya, Basavana Bagewadi]

Kamala Narayana Temple at Degaon in Belgaum District, Karnataka, India. It is a trikūṭa type temple (Built 1174 CE under Kadamba feudatories) [Source: File:Kamala Narayana Temple 25.jpg – Wikimedia Commons]

→ Types of aedicules (both in Siddhesvara Temple, Haveri town, Haveri district, Karnataka, India):

Nagara Style [Source: File:Miniature Tower1 at Siddhesvara Temple at Haveri.JPG – Wikipedia]

Drāviḍa Style [Source: File:Miniature Tower at Siddhesvara Temple at Haveri.JPG – Wikipedia]

→ Kalyani Cālukya temples can have open or closed halls:

Closed hall in Kasivisvesvara Temple, Lakkundi, Gadag district, Karnataka, India [Source: File:Inner mantapa with lathe turned pillars in the Kasivisvesvara Temple at Lakkundi.jpg – Wikipedia]

Open hall in Mahadeva Temple in Itagi, Koppal district, Karnataka, India [Source: File:View of ornate pillared hall in Mahadeva Temple at Itagi.jpg – Wikipedia]

These halls usually have either domical or square ceilings — both types of ceilings originate from the square formed in the ceiling by the four beams that rest on four pillars.

The dome is constructed of ring upon ring of stones, each horizontally bedded ring smaller than the one below. The top is closed by a single stone slab. The rings are not cemented but held in place by the weight of the roofing material above them pressing down on the haunches of the dome. The triangular spaces created when the dome springs from the centre of the square are filled with arabesques.

In the case of square ceilings, the ceiling is divided into compartments with images of lotus rosettes or other images from Sanatanist mythology.

→ Domical bay ceiling in Kaitabheshvara temple at Kubatur near Anavatti in Shimoga district of Karnataka, India. (Built 1100 CE) [Source: File:Domical bay ceiling in Kaitabhesvara temple at Kubatur.JPG – Wikimedia Commons]

Pillars are a major part of Kalyani Cālukya architecture and were produced in two main types:

Pillars with alternate square blocks and a sculptured cylindrical section with a plain square-block base. These are stronger and therefore carry more weight.

Bell-shaped lathe-turned pillars made of soapstone. These are easier to carve and therefore decorate. In some cases, polishing resulted in pillars with reflective properties.

Inventive workmanship was used on soapstone shafts, roughly carved into the required shapes using a lathe. Instead of laboriously rotating a shaft to obtain the final finish, workers added the final touches to an upright shaft by using sharp tools. Some pillars were left unpolished, as evidenced by the presence of fine grooves made by the pointed end of the tool. In other cases, polishing resulted in pillars with fine reflective properties such as the pillars in the temples at Bankapura, Itagi and Hangal. This pillar art reached its zenith in the temples at Gadag.

→ Ornate pillars in Sarasvatī Temple of Trikuteshwara temple complex at Gadag, Gadag district, Karnataka, India [Source: File:Pillars at Sarasvati Temple in Gadag.JPG – Wikimedia Commons]

The temple plan often included a heavy slanting cornice of double curvature, which projected outward from the roof of the open mantapa. This was intended to reduce heat from the sun, blocking the harsh sunlight and preventing rainwater from pouring in between the pillars. The underside of the cornice looks like woodwork because of the rib-work.

→ Major types of Kalyani Cālukya cornices

Straight eaves of Sarasvatī Temple of Trikuteshwara temple complex at Gadag, Gadag district, Karnataka, India [Source: File:Gadag Trikuteshwara temple complex 3.JPG – Wikimedia Commons]

Curved eaves in Mukteshvar Temple of Chaudayyadanapur, Haveri district, Karnataka, India [Source: File:Chaudayyadanapura Mukteshwara temple 11.jpg – Wikimedia Commons]

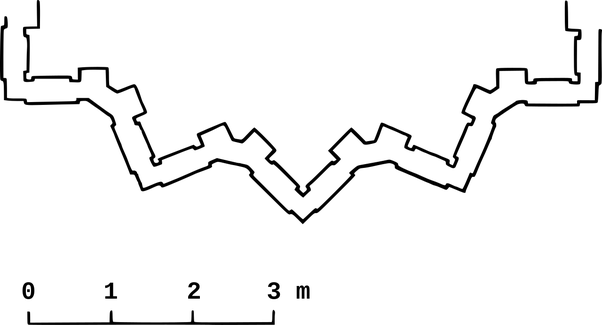

One of the major development of Kalyani Cālukya architecture was terms of floor-plans.

A few temples built of the traditional sandstone feature 16-pointed uninterrupted stellate floor-plan: Trimurti Temple at Savadi, Paramesvara Temple at Konnur and Gauramma Temple at Hire Singgangutti, all of them in Karnataka, India.

Some examples of floor-plans are as follows:

1. Square plan with 5-projections [Source: File:Square floorplan with five projections.svg – Wikipedia]

2. 16-pointed uninterrupted stellate floorplan (one side of the shrine), Trimurti Temple at Savadi in Gadag district, Karnataka, India. (Built 11th century CE) [Source: File:16-pointed uninterrupted stellate plan of Trimurti Temple in Savadi Gadag district.svg – Wikipedia]

3. 32-pointed interrupted stellate floor-plan [Source: File:32-pointed interrupted stellate floorplan.svg – Wikipedia]

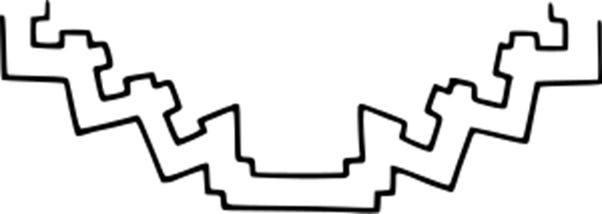

Kalyani region temples:

Temples built in and around the Kalyani region (in Bidar district, Karnataka, India) were quite different from those built in other regions. Without exception, the articulation was nagara, and the temple plan as a rule was either stepped-diamond or stellate. The elevations corresponding to these two plans were similar because star shapes were produced by rotating the corner projections of a standard stepped plan in increments of 11.25°, resulting in a 32-pointed interrupted plan in which three star points are skipped in the centre of each side of the shrine.

→ L2R: Sri Dattatreya Temple, Chattarki, Vijayapura district, Karnataka, India (Built 12th century CE)

32-pointed interrupted floorplan [Source: File:Stepped Diamond floorplan of Dattatreya Temple at Chattarki in Gulbarga district.svg – Wikipedia]

Exterior [Source: Sri Dattatreya Temple, Chattarki, Vijayapura]

Doddabasappa Temple: Doddabasappa Temple is a 12th-century CE temple in Dambal, Karnataka, India. It is the only known Kalyani Cālukya temple (and possibly the only one in India) to follow 24-pointed, uninterrupted stellate floor-plan.

→ [Source: File:Dodda Basappa Temple.JPG – Wikimedia Commons]

→ Kalyani Cālukya temples fall into following categories, with the first two being the most common. Both kinds of temples have two or more entrances giving access to the main hall:

single vimāna and hall, termed ēkakūṭa

2 vimānas sharing a common hall, termed dvikūṭa

3 vimānas sharing a common hall, termed trikūṭa (rare examples) : Mallikarjuna Temple at Sudi, Kamala Narayana Temple at Degaon, Kedareshvara Temple at Balligavi

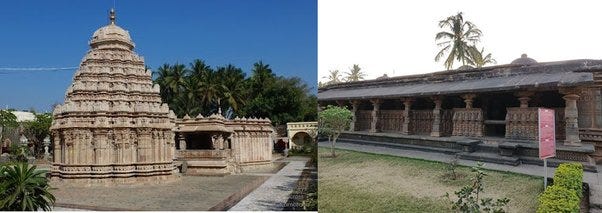

1. Brahma Jinalaya at Lakkundi, Gadag District of Karnataka, India — an ēkakūṭa type temple (Built 11th century CE) [Source: Brahma Jinalaya, Lakkundi – Wikipedia]

2. Kasivisvesvara Temple at Lakkundi, Gadag District of Karnataka, India — an dvikūṭa type temple (Built 11th century CE) [Source: Kasivisvesvara Temple, Lakkundi – Wikipedia]

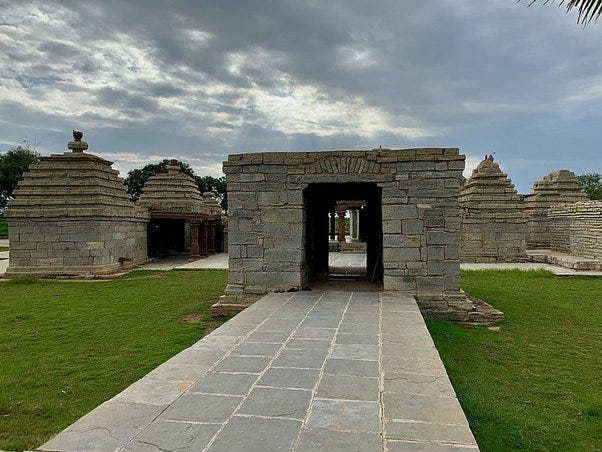

→ Alampur Papanasi Temples — these temples mainly exhibit Nagara or Nagara-esque architecture mainly featuring either Phamsaṇa śikharas or stepped pyramidal śikharas {in this regard the Phamsaṇa śikharas are quite short and except for āmalakas at their top, are difficult to distinguish from Kadamba śikharas of Karnāṭa architecture}. [Source: Alampur Papanasi Temples – Wikipedia]

1. A gateway and some of the temples

2. A Vallabhī Prasāda type temple

3. A relatively simple Phamsaṇa śikhara type temple

→ Palasdeo Palasnath Temple in Ujani Dam reservoir, Ujani, Madha Taluka, Solapur district, Maharashtra, India [Source: Underwater Temple at Palasdeo ( Palasnath Temple)]

→ Japada Bavi, in Dambal, Karnataka, India — a stepped well constructed sometime in 10th-12th century CE. Japadabavi is a merger of two words- Japa (worship) + Bavi (well). This well gets its name because it has been designed in such a way that a person can take bath in the well and perform rituals within the walls of the well. [Source: Japada Bavi, the stepped well of Dambal]

Kanduru Cōḻas introduced the trikūṭa (3 shrine) type temples in Telugu region, starting with Chaya Someswara Temple in Panagal, Nalgonda district of Telangana, India. These were built under their reign in 11th-12th century CE, but saw addditions during Kākatīyas. Trikūṭa type temples have 3 vimānas attached to a common hall, making the temple a composite T-shaped temple. Another temple built during thier reign is Pachala Someswara Temple in Panagal, which is a catuṣkūṭa (4 shrine) type composite temple with 3 vimānas in a line in front of fourth one, attached to common hall.

→ Chaya Someswara Temple has all 3 vimānas featuring Kadamba śikharas. It is a T-shaped Trikūṭa temple [Source: File:Chaya Someswara Temple at Pangal.jpg – Wikimedia Commons]

→ Pachala Someswara Temple has stepped pyramidal vimānas, with varying amounts of decorations. It is a catuṣkūṭa-type Ψ-shaped temple [Source: File:11th 12th century Pachala Someshwara Temple reliefs and mandapams, Panagal Telangana India – 22.jpg – Wikimedia Commons]

At least one example of temple with stepped cylindrical vimāna exists, dateable to Kanduru Cōḻas, and may be the earliest such example in Telugu region. While stepped cylindrical vimānas aren’t exactly rare, they are not common either, and may be independent development from the anyway rare temples found elsewhere.

→ Temple in Lingala village, Lingala mandal, Nagarkurnool district, Telangana, India. Built 12th century CE [Source: Hindu Temple & Inscriptions]

As a feudatory of Kalyani Cālukyas, Kadamba Śāstādēva was appointed as the Mahamaṇḍalēśvara of present-day Goa by Kalyani Cālukya emperor Tailapa II. Śāstādēva later conquered the city of Chandrapur from Śilāhāras and established Goa Kadamba dynasty in 960 CE. The temples constructed under them were relatively simpler compared to those of their overlords Kalyani Cālukyas as well as Kanduru Cōḻas.

→ Mahadeva Temple in Kurdi, Goa, India (Built 10th century CE under Goa Kadambas) [Source: Mahadeva Temple – Kurdi (Curti), Goa]

→ Mahadev Temple at Tambdi Surla, Goa India (Built 12th century CE under Goa Kadambas) [Source: File:Shri Mahadev Temple, Tambdi Surla, Goa.jpg]

12th century CE – 14th century CE

Devagriri Sēuṇas (1187 CE – 1317 CE)

Dwarasamudra Hoysaḷas (1193 CE – 1343 CE)

Devagriri Sēuṇas (1187–1317 CE) initially served as Kalyani Cālukyas. They became independent in 12th century CE, and overthrew Kalyani Cālukyas and Tripuri Kalacuris from Maharashtra. They declined after Delhi Sultanate’s invasion. Temple architecture development under Sēuṇas can be considered the origin point for Marāṭhī Architecture, but some of their temples do follow architecture similar to that of Kalyani Cālukyas.

During Sēuṇa rule in early 13th century CE, 12th century CE Kalyani Cālukya architecture characteristics remained prominent, however, many parts that were formerly plain became decorated — this change is observed in Muktesvara Temple at Chaudayyadanapura and Santesvara Temple at Tilavalli, both in Haveri district. In Tilavalli Temple, all the architectural components are elongated, giving it an intended crowded look. Both temples are built with a Drāviḍa articulation.

There is gradual departure from Kalyani Cālukya architecture characteristics visible in temples constructed under Sēuṇas in Maharashtra, while Kalyani Cālukya architecture characteristics remained stronger in temples of Karnataka.

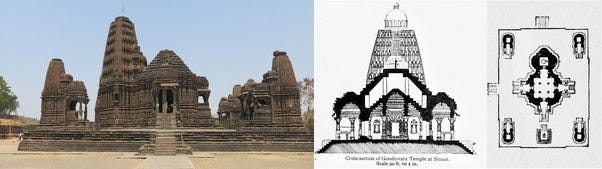

→ Gondeshwar Temple Complex in Sinnar, Nashik district, Maharashtra, India (Built 11th-12th century CE) [Source: Gondeshwar Temple, Sinnar – Wikipedia]

The main temple (centre) has Bhūmija śikhara with a flat ‘strip’ in middle of each face of the tower. The subsidiary temples have Latina śikhara with Candraśālā mesh decorations all over the tower.

Cross section and plan of the site. The temple complex is arranged in Quincunx (termed Pañcāyatana) format. At least since this period, Pañcāyatana format would have been known and implemented in Maharashtra.

→ Savantesvara (Santesvara) Temple in Tilavalli, Haveri district, Karnataka, India (Built 1237 CE under Singhana Sēuṇa II) [Source: Indian History and Architecture]

1. North-east view

2. Front view

3. Hall with Kalyani Cālukya style pillars

→ Mallikarjun Temple in Loni Bhapkar village, Pune district, Maharashtra, India — features the “interrupted” Bhūmija śikhara somewhat similar to Gondeshvar Temple above (Built late 13th century CE) [Source: Mallikarjun Temple – Loni Bhapkar]

→ Aundh Nagnath Temple in Aundha Nagnath in Hingoli district of Maharashtra, India. The base of the temple was constructed under Sēuṇas in 13th century CE. The base shows many of general Kalyani Cālukya architecture characteristics including staggered-square plan and profuse decorations over the string courses & pillars [Source: Aundha Nagnath Jyotirlinga Temple, History, Timings, Darshan]

→ Anandeshwar Temple in Lasur Village, Amravati District, Maharashtra, India — a trikūṭa type temple with an open ceiling hall (similar to Kopeshvar Temple) (Built under Ramacandra (r.1271-1311 CE)) [Source: Anandeshwar Temple Akola – LOST TEMPLE]

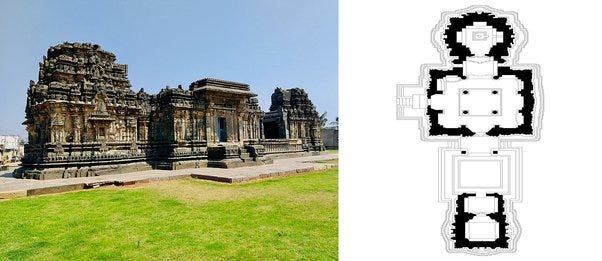

Dwarasamudra Hoysaḷas (1193 CE – 1343 CE) developed Hoysaḷa Architecture sub-style of Karnāṭa architecture. Hoysaḷas were originally from Malenadu, an elevated region in Sahyadri. In 12th century CE, taking advantage of the internecine warfare between Kalyani Cālukyas and Kalyani Kalacuris, they annexed areas of present-day Karnataka and the fertile areas north of Kaveri delta in present-day Tamil Nadu. By 13th century CE, they governed most of Karnataka, minor parts of Tamil Nadu and parts of western Andhra Pradesh and Telangana.

Hoysaḷas were initially feudatories of Kalyani Cālukyas, becoming independent in 1187 CE under Vīra Ballāḷa II (r. 1173 CE – 1220 CE). They maintained matrimonial relations with the Later Cōḻas, while being in conflicts with Pāṇḍyas, Seuṇas and Kākatīyas. Hoysaḷa empire was considerably weakened after invasions by Delhi Sultanate, and was finally replaced by Karnāṭaka Empire.

General architectural features:

Hoysaḷa temples incorporate aediculae and many types of motifs.

Maṇṭapa (hall): The entrance to the hall normally has a highly ornate overhead lintel called makaratōraṇa. Open outer hall is a regular feature in larger Hoysaḷa temples leading to an inner small closed hall and the shrine(s). The open halls which often have seating areas made of stone with hall’s parapet wall acting as a back rest. Most halls follow a staggered-square pattern.

Vimāna (sanctum structure):

Inside of the sanctum structure is plain and square, whereas its outside is profusely decorated and can be stellate (“star-shaped”) or staggered square shaped, or feature a combination of these designs.

The tower of the vimāna itself has usually 3 or 4 storeys while the Śukanāsa has one less storey — these are constructed such that Śukanāsa appears to be a seamless extension of the vimāna.Temples:

Depending on the number of vimānas the temples are classified as: ēkakūṭa (one), dvikūṭa (two), trikūṭa (three), catuṣkūṭa (four) and pañcakūṭa (five).

In temple groups with multiple disconnected temples, such as some twin temples, all essential parts are duplicated for symmetry and balance.

In most cases, temples are placed over a jagati (platform).

Temples built prior to Hoysaḷa independence in mid-12th century CE reflect significant Kalyani Cālukya influences, while later temples retain some features salient to Kalyani Cālukya architecture but have additional decoration and ornamentation features unique to Hoysaḷa artisans.

Below the superstructure of the vimāna are eaves projecting ~0.5m from the wall. Below the eaves two different decorative schemes may be found, depending on whether a temple was built in the early or the later period of the empire.

In the early temples built prior to the 13th century CE, there is one eave and below this are decorative miniature towers. A panel of Sanatanist deities and their attendants are below these towers, followed by a set of 5 different mouldings forming the base of the wall.

In the later temples, during and after 13th century CE, there is a second eave running ~1m below the upper eaves with decorative miniature towers placed between them. The wall images of deities are below the lower eaves, followed by 6 different mouldings of equal size. This is broadly termed “horizontal treatment”.

These 6 mouldings at the base are divided in two sections.

Going from the very base of the wall, the first horizontal layer contains a procession of elephants, above which are horsemen and then a band of foliage.

The second horizontal section has depictions of Sanatanist mythological scenes. Above this are two friezes of yalis or makaras (mythological beasts) and geese.

While medieval Indian artisans preferred to remain anonymous, Hoysaḷa artisans signed their works, which has given researchers details about their lives, families, guilds, etc. Apart from the architects and sculptors, people of other guilds such as goldsmiths, ivory carvers, carpenters, and silversmiths also contributed to the completion of temples. The artisans were from diverse geographical backgrounds and included famous locals.

The entrance to the hall normally has a highly ornate overhead lintel called a makaratōraṇa. The outer and inner halls (i.e. open and closed) have circular lathe-turned pillars having 4 brackets at the top. Over each bracket stands sculptured figures called śālabhañjikā or madanikā. The pillars may also exhibit ornamental carvings on the surface and no two pillars are alike. This is how Hoysaḷa art differs from the work of their former overlords, Kalyani Cālukyas, who added sculptural details to the circular pillar base and left the top plain. The lathe-turned pillars are 16, 32, or 64-pointed: some are bell-shaped and reflect light.

→ Hall Decorations:

Ornate lintel over hall entrance in Chennakeshava temple of Belur, Karnataka, India [Source: File:Belur2 retouched.jpg – Wikimedia Commons]

Madanikā in Chennakeshava temple of Belur, Karnataka, India [Source: File:Shilabaalika on pillar bracket in Chennakeshava Temple at Belur1.jpg – Wikimedia Commons]

Stambha-buṭṭalikā in Chennakeshava temple of Belur, Karnataka, India [Source: File:Sthambha buttalika sculpture in Chennakesava temple at Belur.jpg – Wikimedia Commons]

The open hall which serves the purpose of an outer hall is a regular feature in larger Hoysala temple complexes, leading to an inner small closed hall and the vimāna(s). The open halls which are often spacious have seating areas made of stone with the halls’ parapet wall acting as a back rest. The seats may follow the same staggered square shape of the parapet wall. The ceiling is supported by numerous pillars that create many bays — even the smallest open mantapa has 13 bays. The staggered-square shape is the style used in most Hoysaḷa temples for their open halls. The walls have parapets that have half pillars supporting the outer ends of the roof which allow plenty of light making all the sculptural details visible. The hall ceiling is generally ornate with sculptures, both mythological and floral. The ceiling consists of deep and domical surfaces and contains sculptural depictions of banana bud motifs and other such decorations.

→ Open halls:

Open hall with shining, lathe-turned pillars at Amrutesvara Temple of Amruthapura, Karnataka, India [Source: File:Chikkamagalur Amritheswara navaranga retouched.JPG – Wikipedia]

Domical ornate bay ceiling in open hall of Veera Narayana Temple of Belavadi, Karnataka, India [Source: File:Domical bay ceiling art in outer mantapa of Veeranarayana temple at Belavadi.JPG – Wikimedia Commons]

If the temple is small it will consist of only a closed hall (enclosed with walls extending all the way to the ceiling) and the shrine. The closed hall, well decorated inside and out, is larger than the vestibule connecting the shrine and the hall, and has 4 lathe-turned pillars to support [an occasionally deeply domed] ceiling. The 4 pillars divide the hall into 9 bays resulting in 9 decorated ceilings. Pierced stone screens serve as windows in Navaraṅga (stage play hall) and Sabhāmaṇṭapa (congregation hall) is a characteristic Hoysaḷa stylistic element.

A porch adorns the entrance to a closed hall, consisting of an awning supported by two half-pillars (engaged columns) and two parapets, all richly decorated.

→ Closed Halls:

Ornate lintel and door jamb relief at entrance to inner hall of Harihareshwara Temple at Harihar, Davanagere district, Karnataka, India [Source: File:Ornate lintel and door jamb relief at entrance to inner mantapa in the Harihareshwara temple at Harihar.JPG – Wikimedia Commons]

Lathe turned pillars of closed hall of Chennakeshava Temple Complex at Somanathapura, Mysore district, Karnataka, India [Source: File:Mantapa with lathe turned pillars and domical ceilings in the Chennakeshava temple at Somanathapura.JPG – Wikimedia Commons]

Domical bay ceiling of closed hall of Chennakeshava Temple Complex at Somanathapura, Mysore district, Karnataka, India [Source: File:13th century Keshava Hindu temple Somanathpur India interior 16.jpg – Wikimedia Commons]

The closed hall is connected to the vimāna(s) by vestibule(s). Its outer walls are decorated, but as the size the vestibule is not large, this may not be a conspicuous part of the temple. The vestibule also has a short tower called the Śukanāsa upon which is mounted the Hoysaḷa emblem of a man killing a lion.

→ Vestibule with Hoysaḷa emblem, in Amrutesvara temple of Amruthapura, Chikkamagaluru district, Karnataka, India (Built 1196 CE) [Source: File:Profile of Amrutesvara temple at Amruthapura in Chikkamagaluru district.JPG – Wikimedia Commons]

The highest point of the vimāna is the kalaśa (urn) having the shape of a water pot. This portion of the vimana is often lost due to age and has been replaced with a metallic pinnacle.

Below the kalaśa is a large, highly- sculptured structure resembling a dome which is made from large stones and looks like a helmet. It may be 2m × 2m in size and follows the shape of the shrine.

Below this structure are domed roofs in a square plan, all of them much smaller and crowned with small kalaśas. They are mixed with other small roofs of different shapes and are ornately decorated. The tower of the vimāna usually has 3 or 4 tiers of rows of decorative roofs while the superstructure over śukanāsa has one less tier, making it look like an extension of the main tower.

Below the superstructure of the vimāna are eaves projecting ~0.5m from the wall. Below the eaves two different decorative schemes may be found, depending on whether a temple was built in the early or the later period of the empire.

In the early temples built before 13th century CE, there is one eave and below this are decorative miniature towers. A panel of Sanatanist deities and their attendants are below these towers, followed by a set of 5 different mouldings forming the base of the wall.

In the later temples, during and after 13th century CE, there is a second eave running ~1m below the upper eaves with decorative miniature towers placed between them. The wall images of deities are below the lower eaves, followed by 6 different mouldings of equal size. This is broadly termed “horizontal treatment”.

These 6 mouldings at the base are divided in two sections:

Going from the very base of the wall, the first horizontal layer contains a procession of elephants, above which are horsemen and then a band of foliage.

The second horizontal section has depictions of Sanatanist mythological scenes. Above this are two friezes of yalis or makaras (mythological beasts) and geese.

→ Madanikās below eaves of the vimāna of Chennakeshava Temple (main temple of complex) at Belur, Hassan district, Karnataka, India [Source: File:Madanikas on the roof railings – Chennakesava Temple, Belur 06.jpg – Wikimedia Commons]

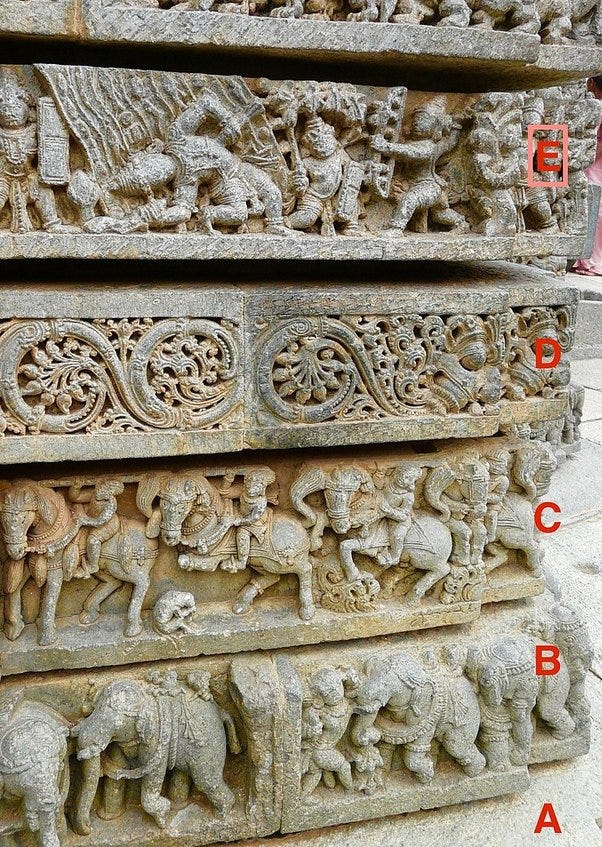

→ The various bands on the lower part of the outer wall at the main Chennakesava Temple at Somanathapura, Mysore district, Karnataka, India

A: the platform

B: marching elephants

C: marching horsemen

D: nature scroll

E: friezes of Sanatanist texts

There are broadly following types of temples depending on number of vimānas:

Ēkakūṭa (one vimāna)

Dvikūṭa (two vimānas) — usually arranged in U-shape i.e. in-line

Trikūṭa (three vimānas) — usually arranged in T-shape

Trikūṭa temples with all vimānas having a tower

Trikūṭa temples with only main central vimāna having a tower

Catuṣkūṭa (four vimānas) — only example is X-shaped Lakshmidevi temple at Doddagaddavalli

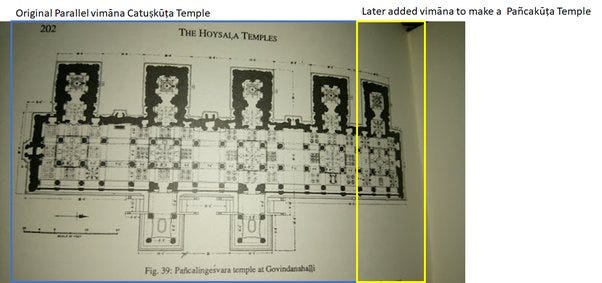

Pañcakūṭa (five vimānas) — only example is In-Line plan Panchalingeswara Temple in Govindanahalli

→ Brahmeshvara Temple in Kikkeri village, Mandya district of Karnataka state, India — Ēkakūṭa temple constructed directly over the ground without any platform (Built 1171 CE by Bammave Nāyakiti)

[Source: File:Brahmeshvara Temple, Kikkeri (79).jpg – Wikimedia Commons]

[Source: File:12th century Brahmesvara temple, Kikkeri Karnataka.jpg – Wikimedia Commons]

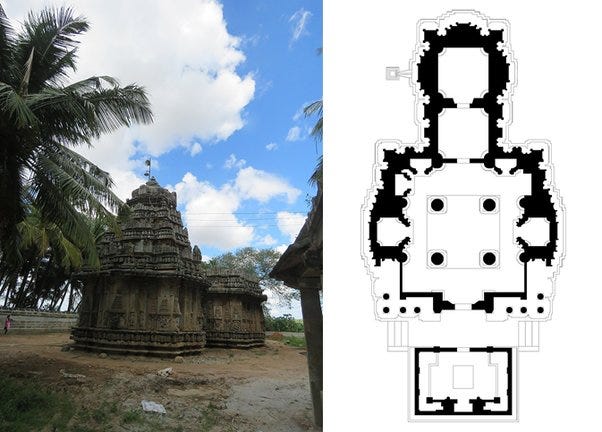

→ Hoysaleswara Temple in Halebidu (then capital Dwarasamudra), Hassan district, Karnataka, India — Dvikūṭa type temple

[Source: Go Heritage Run – Halebidu routes – Go Heritage Runs – Run, Fun, Travel – Run-vacations]

[Source: File:12th century Halebid Shiva temple plan annotated.jpg – Wikimedia Commons]

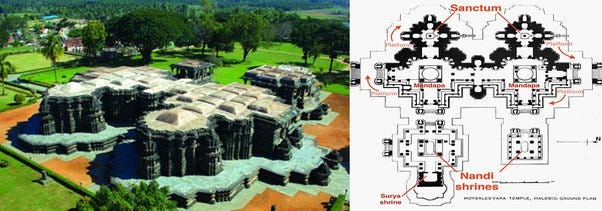

→ Chennakeshava Temple at Somanathapura, Mysore district, Karnataka, India — Trikūṭa type temple with all vimānas having towers (Built 1258 CE under Commander-general Sōmanātha)

[Source: File:Chennakeshava temple at Somanathapura, a top view.jpg – Wikimedia Commons]

[Source: File:Chennakesava temple, Somanathapura.jpg – Wikimedia Commons]

→ Lakshmidevi temple at Doddagaddavalli in Hassan district, Karnataka, India — X-shape Catuṣkūṭa type temple with 3 Kadamba style and 1 Drāviḍa style superstructures [Source: File:Ariel view of Lakshmi Devi temple at Doddagaddavalli.JPG – Wikipedia]

→ Panchalingeswara Temple in Govindanahalli, Mandya district, Karnataka, India — Pañcakūṭa type temple with all vimānas connected to single hall. It was originally a Catuṣkūṭa temple, with a vimāna later added to make it a Pañcakūṭa temple. The later addition made the temple asymmetric.

View of the temple [Source: Top Temples Of Hoysala Dynasty | Listly List]

Panchalingeswara Temple was originally a Catuṣkūṭa temple, with a vimāna later added to make it a Pañcakūṭa temple. The later addition made the temple asymmetric. [Image below modified from image is S Shettar’s The Hoysala Temples, sourced from The Panchalingeshwara Temple, Govindanahalli, Mandya]

There are 2 main types of Hoysaḷa temple complexes:

Regular temple complexes with one main temple and one or more subsidiary temples — examples include Hoysalesvara Temple Complex at Halebidu, Chennakesava Temple Complex at Belur etc.

Twin Temples where 2 [nearly] identical temples are constructed — examples include Nageshvara-Chennakeshava Temples at Mosale, Nagalapura twin temples etc.

→ Nageshvara-Chennakeshava Temples at Mosale, Hassan district, Karnataka, India [Source: File:Twin Temples Nageshswara & Chenna Kesava Temple – Mosale.jpg – Wikimedia Commons]

→ Examples of relatively uncommon Hoysaḷa vimānas:

1. Side view of Chennakesava Temple, Somanathapura, Mysore district, Karnataka — the floor -plan is stellate. It is an example of relatively less common sanctum tower with miniature horizontal and vertical spires in a grid like fashion (called Bhūmija śikhara) [Source: File:Close up of Hoysala style shrine and sikhara with decorative molding frieze in the Chennakeshava temple at Somanathapura.jpg – Wikipedia]

2. Side view of Sri Moole Shankara Temple in Turvekere, Tumkur district, Karnataka, India — features interrupted Bhūmija śikhara i.e. the grid on each face is ‘interrupted’ by a planar section [Source: Team G Square]

3. Bhaktavatsala Swamy temple in Belagola, Srirangapatna, Mandya district, Karnataka — a rare example of circular temple (Built 12th century CE) [Source: Temples of Karnataka – Part IV]

14th century CE – 17th century CE

Kāmpilī kingdom (1294 CE – 1328 CE)

Karnāṭaka Empire (1336 CE – 1646 CE)

Sāntaras (7th century CE – 18th century CE)

Pemmasani Nāyakas (1441 CE – 1685 CE)

Keladi/Ikkeri Nāyakas (1499 CE – 1763 CE)

Jataprolu Kollapur Saṁsthāna (1507 CE – 1948 CE)

Delhi Sultanate’s invasions caused the fall of Sēuṇas, Hoysaḷas and Kākatīyas, and later on Kāmpili kingdom, and most of Deccan region came under its control. The Madurai Pāṇḍiya empire also fell, although Pāṇḍiyas continued to rule from Tenkasi & Tirunelveli in Tamil Nadu till ~17th century CE. This period saw the rule of Delhi Sultanate, Bahamani Sultanate & its successor Deccan Sultanates and finally Second Gūrkāni empire in the Deccan region. Soon after, rebellions against Delhi Sultanate began, with primary participation from Kondavidu Reddis (1325–1448 CE) & Musunuri Nāyakas (1333–1368 CE) who remained significant in Telugu regions for a short time.

Kāmpili kingdom was a short lived kingdom in north-eastern parts of the present-day Karnataka. It was founded Hoysaḷa commander Siṅgēya III (1280 CE – 1300 CE) and continued till his son and successor Kāmpilidēva (r. 1300 CE – 1327/28 CE) was defeated by Delhi Sultanate.

Soon afterwards, political power in Karnāṭa and Telugu regions was mainly split between Karnāṭaka Empire and Bahamani Sultanate, with some areas under control of Gajapati empire (1434–1541 CE) as well. Most of Maharashtra came under control of Marāṭhā empire.

Deccan sultanates were 5 Mohammedan late-medieval sultanates namely Ahmadnagar (Nizām Šāhī; 1490–1636 CE), Berar (Imād Šāhī; 1490–1572 CE), Bijapur (Ādil Šāhī; 1490–1686 CE), Bidar (Bārid Šāhī; 1518–1619 CE) and Golconda (Qutb Šāhī; 1518–1687 CE). The sultanates became independent during the break-up of Bahmanī Sultanate. In 1490 CE, Ahmadnagar declared independence, followed by Bijapur and Berar in the same year. Golconda became independent in 1518 CE, and Bidar which was already de facto independent, declared independence in 1542 CE. Later on Ahmadnagar conquered Berar, and Bijapur conquered Bidar.

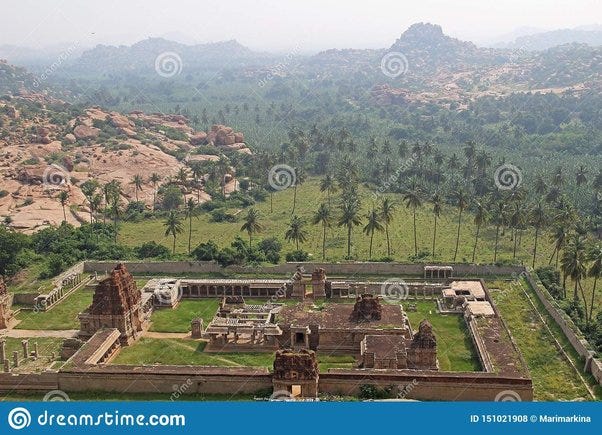

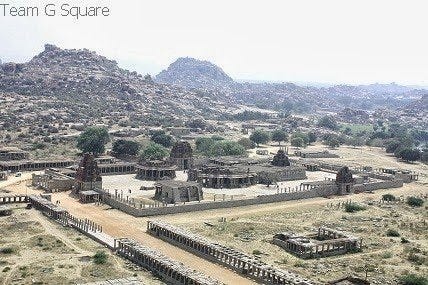

Under Kāmpili kingdom, some of the last trikūṭa temples incorporating Kadamba śikhara were constructed, on Hemakuta hill in Hampi, Karnataka, India. Hampi would later become the capital of Karnāṭaka Empire.

→ A trikūṭa Śiva temple on Hemakuta hill in Hampi built by Kāmpilidēva [Source: File:Shiva temple on Hemakuta hill 3.JPG – Wikimedia Commons]

Karnāṭaka empire’s rule led to the development of the eponymous Karnāṭaka Architecture sub-style.

The origins of Karnāṭaka empire’s first dynasty Saṅgamas is controversial, with possible relationships with Hoysaḷas, Kāmpili kingdom and Kākatīyas. The original capital of Karnāṭaka Empire was Anegundi (in Koppal district, Karnataka), then shifted to Vijayanagara under the reign of Bukka I. Battle of Talikota (23 January 1565) led to the loss of the capital Vijayanagara, causing the empire to establish its capital in Penukonda then Chandragiri (both in present-day Andhra). Finally, Deccan Sultanates captured remaining Karnāṭaka territories with the last ruler Śrīraṅga III taking refuge and dying in Maisūru Saṁsthāna.

Karnāṭaka Empire’s feudatories included Sāntara dynasty (ruling parts of Malenadu & Tulu Nadu), Pemmasani Nāyakas (1441 CE – 1685 CE) in Gandikota (Telugu region), Maisūru Saṁsthāna (1399 CE – 1948 CE), Keladi/Ikkeri Nāyakas (1499 CE – 1763 CE) and Jataprolu Kollapur Saṁsthāna (1507 CE – 1948 CE). These later became independent following the decline of the empire.

Historically, Karnāṭaka empire was ruled by following four dynasties:

Saṅgama dynasty (1336 CE – 1484 CE)

Saluva dynasty (1485 CE – 1505 CE) [Hadavalli line]

Tuluva dynasty (1505 CE – 1570 CE)

Aravīḍu dynasty (1542 CE – 1646 CE)

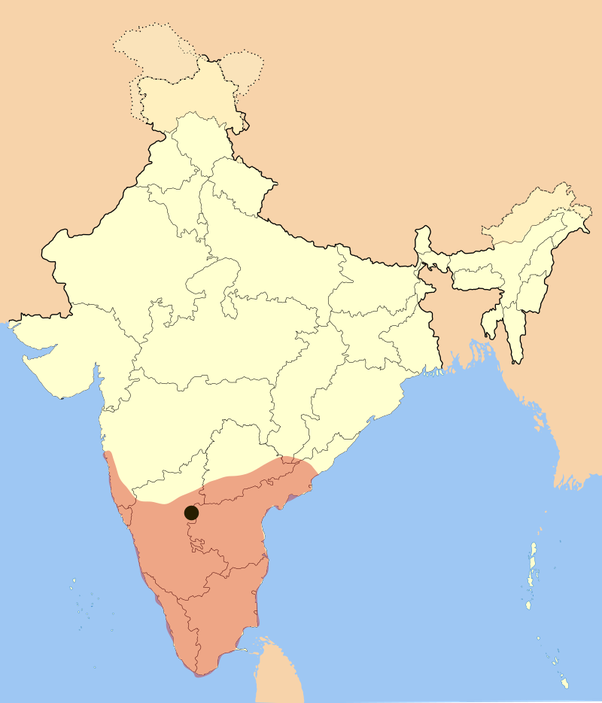

→ Extent of Karnāṭaka Empire, 1446 CE, 1520 CE [Source: File:Vijayanagara-empire-map.svg – Wikimedia Commons]

Karnāṭaka Architecture shows a marked resemblance to Drāviḍa architecture, although much of the features of earlier Karnāṭa temples remain. The main entrance tower of the temples is termed rāyagōpuram. Towering gateways constructed under Karnāṭaka empire are nearly to completely identical to that typical Drāviḍa architecture.

Due to construction activities undertaken by Karnāṭaka empire, tall gateways and colonnaded halls became more popular in temple complexes. Its influence in Telugu region continued after the fall of its capital Vijayanagara, since the capital was established in Penukonda (Anantapur district, Andhra) then Chandragiri (Chittoor district, Andhra).

Their activities in Telugu region include most existing structures of Srisailam Mallikarjuna Temple Complex (Kurnoool district, Andhra), original Lower and Upper Narasimha Temples of Ahobilam (Kurnoool district, Andhra), hundred pillared hall and main gateway of Srikalahasteeswara temple complex (Chittoor district, Andhra), Lepakshi Veerabhadra Temple Complex (Anantapur district, Andhra). Kanipakam Vinayaka Temple Complex (Chittoor district, Andhra) was expanded under them in 1336 CE. They extended patronage to Simhachalam Lakshmi Varaha Narasimha Temple Complex, mainly under its Tuluva dynasty: Kr̥ṣṇadēva erected a Jayastambha (pillar of victory), he and his wives gifted ornaments.

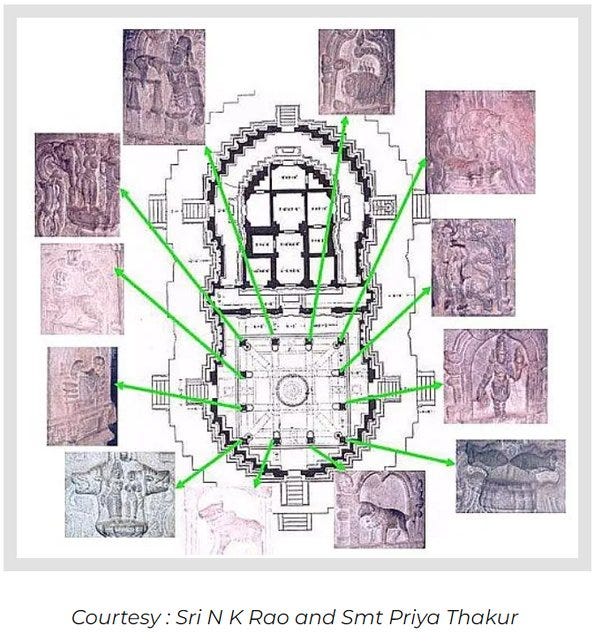

General architectural features:

The temples are usually surrounded by a strong enclosure.

The sanctum towers are mostly of Drāviḍa or Kadamba style.

The main entrance tower of the temples is termed rāyagōpuram, and can be higher than the sanctum towers of the temples.

The pillars of the temples featured extensive decorations particularly sculptures of mythological figures like Yāḷi and sculptures of horse riders, termed Kudure Gombe (Horse doll).