Temple Architecture Styles : Balinese Architecture

Balinese Architecture1 is the style of temple architecture practised by Balinese Sanatanists, and is mainly found in Bali island of Indonesia, with a few examples outside.

General architecture features:

Pura: The temple/temple complex is called Pura. Puras are designed as open air places of worship within enclosed walls, connected with a series of intricately decorated gates between their compounds.

The design, plan and layout of the temple complex follows the trimaṇḍala (3 zone) concept of Balinese space allocation. The 3 zones are arranged according to a sacred hierarchy:

Nista maṇḍala (jaba pisan): the outer zone. This zone usually takes the form of an open field or a garden that can be used for religious dance performances, or act as an additional space for preparations during religious festivals. It is entered through a split gate called candi bentar.

Madya maṇḍala (jaba teṅah): the middle zone. This is where the activity of adherents takes place, and also the location for supporting facilities of the temple. In this zone usually several pavilions (bale) are built, like bale kulkul (wooden slit drum tower), bale gong (gamelan pavilion), wantilan (meeting pavilion), bale pesandekan, and bale perantenan (temple's kitchen). It is entered from outer zone through another Candi bentar.

Utama maṇḍala (jero): the holiest and the most sacred zone within the complex. This enclosed and typically highest of the compounds usually contains a padmāsana, the towering lotus throne of the supreme deity, Acintya (Saṅ Hyaṅ Widhi Wasa, or "All-in-one Deity", in modern Balinese), peliṅgih mēru (a multi-tiered tower-shrine), and several pavilions, like bale pawedan (chanting pavilion), bale piyasan, bale pepelik (offering pavilion), bale paṅguṅgan, bale murda, and gedoṅ peñimpenan (storehouse of the temple's relics). It in entered from middle zone via a gateway called kori aguṅ or paduraksa.

The designs of outer and middle zones are somewhat flexible. The slit drum pavillion can be built as outer corner tower. The temple kitchen can be located in outer zone instead.

→ Balinese Temple Complex [Source: File:Bali temple diagram.png]

Types of temple complexes:

Pura Desa : Dedicated to Brahmā and local sprits. It is usually located in centre of a village and acts as the religious and cultural centre

Pura Puseh : Dedicated to Viṣṇu and human founders of the village. It is usually situated facing Bali’s most sacred and largest mountain, a stratovolcano named Mount Agung[1] (locally called Gunuṅ Aguṅ).

Pura Dalem : Dedicated to one or more of Śiva, Durgā, Kālī, Mother nature, Banaspatiraja (barong), Sang Bhuta Diyu, Sang Bhuta Garwa, and other deities. It is also common for a pura dalem to have a big tree like a banyan tree or a kepuh which is usually also used as a shrine. Pura Dalem is typically located next to the graveyard of the deceased prior to ṅaben (cremation) ceremony. It is also dubbed “Temple of the dead” and usually faces the sea.

Pura Mrajapati : Dedicated to Prajāpati.

Pura Segara (Sea Temple) : Located near the sea

Pura Tirta (Water temples) : temple complexes that along with religious function, also have water management function as part of Subak[2] irrigation system. The priests in these temple complexes have authority to manage the water allocation among rice paddies in the villages surrounding the complex. Some of such temples are noted for their sacred water and having petirtān or sacred bathing pool for cleansing ritual. Other water temples/temple complexes are built within lakes.

Pura Kahyaṅan Jagad or Pura Kahyaṅan Padma Bhuwana : built upon mountain or volcano slopes. The mountains are considered as the sacred magical and haunted realm, the abode of deities or hyang.

They are the 9 holiest places of worship on the island marking the 8 cardinal directions and center point. Built at strategic locations, they are meant to protect the island and its people from evil spirits. These temples belong to every Balinese on the island (as opposite to the other temples, which are the property of the village or town in which they sit).

Development

The development of Balinese temple architecture primarily occurred during the rule of Bali Kingdom (914 CE – 1908 CE)[3].

10th century CE – 12th century CE

Bali Kingdom : Warmadēwa dynasty (c. 914 CE – 12th century CE)[4]

In the early 10th century CE, a king called Sri Kesari Warmadēwa issued Belanjong pillar inscription found near the southern strip of Sanur beach. It is the oldest inscription found in Bali that names the ruler who issued it. The pillar is dated 914 CE according to the Indian Saka calendar. Three other inscriptions by Kesari are known in central Bali, which suggest conflict in the mountainous interior of the island. Sri Kesari is the first known ruler to bear the Warmadēwa title, which was used by rulers for several generations prior to Javanese expansion.

It is not known precisely where the capital of the kingdom was during the 10th and 11th centuries CE, but the political, religious and cultural centre of the kingdom may have been in the present-day Gianyar Regency, inferred from the concentration of archaeological finds in this area.

Warmadewa dynasty seems to have been influenced by Mataram kingdom when Mahēndradattā of Mataram kingdom’s Isyana dynasty became the queen consort of Bali king Udayana Warmadēwa, as reflected in the rock-cut Candis of Gunung Kawi[5] in Bali, carved during 11th century CE.

After Warmadēwa dynasty, their descendants and their link to Javanese court, there is no continuous further detailed information found about the rulers of Bali. It seems that Bali had developed a new native dynasty quite independent from Java.

In the late 13th century CE, Bali once again appeared in Javanese sources. In 1284 CE, Javanese king Kertanegara launched a military offensive expedition against the Balinese ruler. This expedition seems to have integrated Bali into Singhasari’s realm. However, after the Jayakatwang rebellion of Gelang-gelang in 1292 CE that led to the death of Kertanegara and the fall of Singhasari, Java was unable to assert their rule upon Bali, and once again Balinese rulers enjoyed their independence from Java.

Javanese contacts led to a deep impact on the language of Bali which was impacted by the Kawi language, a style of Old Javanese. The language is still used in Bali though is rare.

Temples:

The stone cave temple and bathing place of Goa Gajah, near Ubud in Gianyar, was made around the same period. It shows a combination of Buddhist and Sanatanist Shivaite iconography. Several carvings of stūpas, stūpikās (small stūpas), and images of Bōddhīsattvas suggest that Warmadewa dynasty was a patron of Mahayana Buddhism. Nevertheless, Sanatanism was also practised in Bali during this period.

Associated stepwells and gateways mark their appearance at least since this period, as seen in Goa Gajah (Elephant’s Cave)[6] and Goa Garba (Cave of the Womb)[7] respectively.

→ Warmadēwa period religious artifacts examples:

The bell-shaped stūpikā similar to Central Javanese Buddhist art, containing Buddhist votive tablets (8th-century CE) [Source: File:Stupika and artifacts Bali 8th century.jpg - Wikimedia Commons]

→ Warmadēwa period religious structures examples:

Gunung Kawi Rock-cut Temple-cum-funerary complex in Tampaksiring, north east of Ubud in Bali, Indonesia (Built 11th century CE) [Source: File:1 gunung kawi temple.jpg - Wikimedia Commons]

Candi Tebing Jukut Paku, Gianyar Regency, Bali, Indonesia (Built possibly 11th-12th century CE) [Source: Candi Tebing Jukut Paku, Gianyar Regency, Bali, Indonesia]

Goa Gajah (Elephant's Cave), Gianyar Regency, Bali, Indonesia — the carved face and interior are quite different from Candi Tebing Jukut Paku & Gunung Kawi, gatekeeper statues can be seen. Associated stepwells mark their appearance at least since this cave temple. (Built 11th century CE) [Source: Goa Gajah, Gianyar Regency, Bali, Indonesia]

Goa Garba (Cave of the Womb), Gianyar Regency, Bali, Indonesia — associated gateways mark their appearance at least since this temple (Built possibly 11th century CE) [Source: Goa Garba, Gianyar Regency, Bali, Indonesia]

14th century CE – 15th century CE

Bali Kingdom: Majapahit Vassalage (1343 CE – 15th century CE)

Polities:

In East Java, Majapahit under the reign of queen regnant Tribhuwana Wijayatunggadewi and her Prime Minister Gajah Mada, saw the expansion of Majapahit armada into neighbouring islands in Indonesian archipelago including Bali. According to Babad Arya Tabanan manuscript, in 1342 CE Majapahit troops led by Gajah Mada assisted by his general Arya Damar, the regent of Palembang, landed in Bali. After seven months of battles, Majapahit forces defeated the Balinese king in Bedulu (Bedahulu) in 1343. After the conquest of Bali, Majapahit distributed the governing authority of Bali among Arya Damar's younger brothers: Arya Kenceng, Arya Kutawandira, Arya Sentong and Arya Belog. Arya Kenceng led his brothers to govern Bali under Majapahit banner and became the ancestor of Balinese kings of Tabanan and Badung royal houses. Javanese Majapahit empire influenced Bali both culturally and politically. The whole court of Majapahit fled to Bali following the conquest by Mohammedan Demak Sultanate rulers in 1478 CE, in effect resulting in the transfer of the whole culture.

According to Babad Dalem manuscript (composed in 18th century CE), the conquest of Bali by Majapahit was followed by the installation of a vassal dynasty in Samprangan in the present-day Gianyar regency, close to the old royal centre Bedulu. This event took place in mid-14th century CE. The first Samprangan ruler Sri Aji Kresna Kepakisan sired three sons: of these the eldest son Dalem Samprangan succeeded to the rulership but turned out to be an incompetent ruler, while his youngest brother Dalem Ketut founded a new royal seat in Gelgel while Samprangan lapsed in obscurity.

By 16th century CE, Puri (Balinese court) of Gelgel become a powerful polity in the region. The successor of Dalem Ketut, Dalem Baturenggong, reigned in the mid-16th century CE under whose reign, Gelgel kingdom reached its peak as Lombok, western Sumbawa and Blambangan on easternmost Java, were united under Gelgel's suzerainty. After 1651 CE Gelgel kingdom began to break up due to internal conflicts, and was divided into nine kingdoms.

Temples:

→ Pura Maospahit is the only temple in Bali that was built using the concept of Pañca-maṇḍala. Unlike most Balinese Sanatanist temples which are arranged with the most sacred inner sanctum (jero) to the direction of the mountain, Pañca-maṇḍala places the most sacred jero area at the center of the temple complex. This form of arrangement is similar to the ancient temples of Majapahit or to the kraton palaces of ancient Java. (Built 13th century CE onwards) [Source: Pura Maospahit Denpasar, Denpasar Regency, Bali, Indonesia]

17th century CE – 19th century CE

Nine Kingdoms Period (17th century CE – 19th century CE)

Polities:

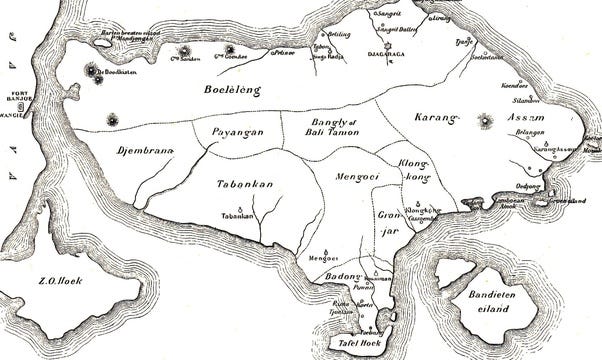

After 1651 CE Gelgel kingdom began to break up due to internal conflicts, and was divided into nine kingdoms: Klungkung, Buleleng, Karangasem, Mengwi, Badung, Tabanan, Gianyar, Bangli and Jembrana. These minor kingdoms developed their own dynasty, built their own Puri (Balinese palace compound) and established their own government. Nevertheless, these nine kingdoms of Bali admitted Klungkung leadership, that the Dewa Agung kings of Klungkung are their primus inter pares among Balinese kings, and deserved the honourable titular as the king of Bali. In following centuries, the various kingdoms fought a succession of incessant wars among themselves, although they accorded Dewa Agung a symbolic paramount status of Bali. This led to complicated relations amongst Balinese rulers, as there were many kings in Bali. This situation lasted until the coming of the Dutch in the 19th century CE.

→ [Source: File:Kaart van het eiland Bali.jpg - Wikimedia Commons]

Temples:

→

Pura Taman Ayun Complex in Mengwi district, Badung Regency, Bali, Indonesia — the water body surrounding it is part of the subak system. (Built 1634 CE under Mengwi kingdom’s ruler Gusti Agung Putu) [Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pura_Taman_Ayun]

Inner gateway (left) and Padmāsana (right) of Puri Agung Denpasar (Satria) Complex in Denpasar Regency, Bali, Indonesia (Built 1788 CE onwards; Badung kingdom) [Source: Puri Agung Denpasar (Satria), Denpasar Regency, Bali, Indonesia]

Tirta Gaṅgā Complex in Karangasem Regency, Bali, Indonesia — this complex houses Karangasem royal water palace, bathing pools and a petirtān temple (Built 1946 CE) [Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tirta_Gangga]

Republik Indonesia (1949 CE – present)

→ Padmāsana (left) and Candi Bentar (right) of Pura Agung Jagatnatha in Denpasar Regency, Bali, Indonesia [Source: Pura Agung Jagatnatha, Denpasar Regency, Bali, Indonesia]

Structural Details

Decorative Elements

Decorative motifs:

Common decorative motifs in Balinese temples include common Sanatanist symbols like Svāstika (also auspicious in Buddhism and Jainism), grotesque termed Bhoma

→ Common auspicious symbols reliefs examples:

Svāstika on Pura Goa Lawah in Pesinggahan, Dawan Subdistrict, Klungkung, Bali, Indonesia [Source: https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/f/f8/A_Hindu_Swastika_at_Goa_Lawah_Temple_Bali_Indonesia.jpg/1920px-A_Hindu_Swastika_at_Goa_Lawah_Temple_Bali_Indonesia.jpg]

Bhoma:

Bhoma (earth-born -> son of earth)2 , or rather his face, is a grotesque which decorates certain parts of the Balinese temple complex. Bhoma’s mouth is considered a good omen to ward off evil spirits. It is similar in form and function to Javanese Kāla motif, but unlike Kāla, Bhoma’s mouth may be flanked by hands.

In Balinese mythology, Bhoma is the son of Viṣṇu (Wisnu) and Pr̥thvī (Pertiwi).

→ Bhoma reliefs examples:

Bhoma head guarding the top of the portal to a Balinese temple in Singapadu, Bali, Indonesia — the lower Bhoma head is flanked by hands [Source: https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/a2/Singapadu_Bali_Pura-Puseh-Desa-03.jpg/800px-Singapadu_Bali_Pura-Puseh-Desa-03.jpg]

Léyak:

In Balinese folklore, Léyak3 is is a mythological figure in the form of a flying head with entrails (heart, lung, liver, etc.) still attached. Léyak are said to fly trying to find a pregnant woman in order to suck her baby's blood or a newborn child.

Rangda is the queen of Léyak.

→ Léyakmotifs examples:

Rangda statue in a temple in Bali, Indonesia [Source: https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/5/58/Rangda_statue.jpg/800px-Rangda_statue.jpg]

Gateways

A Balinese Temple Complex usually has 2 types of gateways — candi bentar[8] and paduraksa a.k.a. kori aguṅ[9]. Paduraksa is usually higher than Candi Bentar. Both types of gateways are associated with both Javanese and Balinese architecture, both religious and secular. Balinese style gateways are generally highly decorated.

Paduraksa / Kori Aguṅ:

The term “Paduraksa” is used more often for Sanatanist temples, while other uses (including mosques) use the term “Kori Aguṅ”.

In Balinese temple architecture, a major temple complex usually has triple paduraksa gate, a main largest and tallest paduraksa, flanked by 2 smaller ones. Daily devotees and casual visitors usually use the side doors, while the main door is kept locked, except during religious festivals.

The entrance of Paduraksa may have the mouth of Bhoma[10] carved/placed over it — Bhoma’s mouth is considered a good omen to ward off evil spirits.

→ Paduraksa examples:

Paduraksa (singular structure) on left and Candi Bentar on right [Source: File:Kuta Bali Indonesia Pura-Gunung-Payung-01.jpg]

A highly ornate paduraksa with Bhoma carved over the entrance [Source: File:Singapadu Bali Pura-Puseh-Desa-02.jpg]

An arched gateway in Pura Uluwatu [Source: An Introduction to Balinese Temples - Sailingstone Travel]

A triple paduraksa in Pura Besakih on Mount Agung, Bali, Indonesia [Source: File:Besakih02.jpg - Wikimedia Commons]

Candi Bentar:

Candi bentar has a form like an Sanatanist/Buddhist temple proper (Indonesian term for them is candi) but split perfectly in 2 to create a symmetrical image. Candi bentar characteristically has a stepped profile, which can be heavily decorated in the case of Balinese style. The 2 inner surfaces are always left sheer and unornamented giving the impression that the structure has been split in 2.

The current prevalence of candi bentar is probably owed Majapahit influence on Javanese and Balinese architecture — the oldest known candi bentar still standing is Wriṅiṅ Lawaṅ in Trowulan, Java that dates to 14th century CE Majapahit era.

→ Candi bentar examples:

A candi bentar in Kebun Raya, Bali, Indonesia [Source: File:Kebun Raya Bali Candi Bentar IMG 8794.jpg]

Pavilions (Bale)

There are many different types of pavilions found in Balinese temple complexes for different purposes.

Bale Kulkul (Slit-Drum Pavilion)

Bale Kulkul (Slit-Drum Pavilion) [11] houses a slit-log drum (kulkul), and is built like a a watchtower consisting of a base and topped with a wooden structure where the slit drum is hanged. A roof canopy provides shelter for the slit drum. A slit drum[12] is a percussive instrument (not a true drum) usually made from timber or bamboo

In Balinese temple complexes, the slit-drum pavilion is usually found straddling onto a wall corner. It is usually constructed of masonry structure and heavily decorated with mythic figures. The base of a temple slit-drum pavilion reaches significant height, and is divided into 3 levels from bottom to top: tepas, batur, and sari. The tepas level represents the underworld realm bhur (Saṁskr̥ta bhūlōka) and is decorated with figures of giant creatures. The batur level represents the realm of the human bhuwah (Saṁskr̥ta bhuvarlōka) and is decorated with animals. The sari level represents the realm of deities swah (Saṁskr̥ta svargalōka) and is decorated with birds and other celestial figures. On top of the swah level is the wooden pavilion where the slit-drum is kept.

There are 2 kinds of slit-drum — Kulkul Dewa (slit-drum of deities) and Kulkul Bhuta (slit-drum of bhūtas). Kulkul Dewa is always made of the wood of jackfruit tree and is struck in a very slow rhythm to call the deities, Kulkul bhuta is made of bamboo and is struck to summon Bhūta kala (often translated to English word [malevolent] demons, but closer to Hellenic ambivalent daemons or general spirits).

→ Bale kulkul in Pura Taman Ayun, Mengwi subdistrict, Bali, Indonesia [Source: File:Drum Tower, Pura Taman Ayun 1495.jpg]

Wantilan (Meeting pavilion/Gathering pavilion)

Wantilan (Meeting pavilion/Gathering pavilion)[13] is the largest type of pavilion in Balinese temple complexes. The wantilan is an imposing pavilion built over a low plinth and topped with 2 or 3 tiered pyramidal roofs. It has no walls. The enormous roof is traditionally supported by 4 main posts and 12 or 20 peripheral posts. The roof is normally covered with clay pantiles or thatched material.

The space of a wantilan is usually of a simple flat floor, sometimes with a stage on the other end, where gamelan or traditional dances can be performed. Sometimes the floor is designed like a rectangular amphitheatre facing a central raised stage — this kind of wantilan is usually used for holding a cockfighting ceremony.

→ Wantilan at Pura Taman Ayun, with a lowered central area for a stage used to hold a cockfighting ceremony. [Source: File:Cockfighting Pavilion, Pura Taman Ayun 1490.jpg]

Peliṅgih mēru

Peliṅgih mēru[14] is a wooden, pagoda-like structure with a masonry base, a wooden chamber and multi-tiered diminishing thatched roofs. It always has odd number of roofs, either one of 3, 5, 7, 9, or 11.

A Peliṅgih mēru contains the principle shrine of the temple complex; in case of multiple towers, the higher ones are more important.

→ A number of meru towers in different tiers height at Pura Taman Ayun, Bali, Indonesia [Source: File:Taman Ayun.jpg]

Padmāsana (Lotus throne)

The word is borrowed from Saṁskr̥ta Padmāsana (lotus pose, lotus throne). Padmāsana4 is the most sacred part of the complex, denoting the throne of the Supreme Deity (Acintya or Saṅ Hyaṅ Widhi Wasa). The throne is empty, but can have an image of the supreme deity carved on it.

The introduction of the Padmāsana shrine as an altar to the Supreme Deity was attributed to Dang Hyang Nirartha5, the priest of King Batu-Renggong. Dang Hyang Nirartha was a Javanese priest, poet, architect, and religious teacher, arriving in Bali in 15th or 16th century CE and reforming Bali Āgama Dharma.

The term Saṅ Hyaṅ Widhi Wasa (Divine Order) was actually coined in 1930s by Protestant missionaries to describe their god. But after Indonesian independence and stipulation of all religions to be monotheistic, the term also began to be used by Balinese Sanatanists

→ Padmāsana examples:

[Source: File:Ubud, Pura Taman Saraswati (6827593602).jpg]

Padmāsana of Pura Agung Jagatnatha in Denpasar, Bali, Indonesia [Source: https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/c/cf/Jagatnatha_Great_Temple_Denpasar.jpg/800px-Jagatnatha_Great_Temple_Denpasar.jpg

Triple Padmāsana in Pura Besakih, Bali, Indonesia [Source: File:COLLECTIE TROPENMUSEUM Godenzetels op het tempelcomplex bij Besakih TMnr 10027767.jpg]

Temples and Temple Complexes

Temple Complex design:

The design, plan and layout of the temple complex follows the trimaṇḍala (3 zone) concept of Balinese space allocation. The 3 zones are arranged according to a sacred hierarchy:

Nista maṇḍala (jaba pisan): the outer zone. This zone usually takes the form of an open field or a garden that can be used for religious dance performances, or act as an additional space for preparations during religious festivals. It is entered through a split gate called candi bentar.

Madya maṇḍala (jaba teṅah): the middle zone. This is where the activity of adherents takes place, and also the location for supporting facilities of the temple. In this zone usually several pavilions (bale) are built, like bale kulkul (wooden slit drum tower), bale gong (gamelan pavilion), wantilan (meeting pavilion), bale pesandekan, and bale perantenan (temple's kitchen). It is entered from outer zone through another Candi bentar.

Utama maṇḍala (jero): the holiest and the most sacred zone within the complex. This enclosed and typically highest of the compounds usually contains a padmāsana, the towering lotus throne of the supreme deity, Acintya (Saṅ Hyaṅ Widhi Wasa, or "All-in-one Deity", in modern Balinese), peliṅgih mēru (a multi-tiered tower-shrine), and several pavilions, like bale pawedan (chanting pavilion), bale piyasan, bale pepelik (offering pavilion), bale paṅguṅgan, bale murda, and gedoṅ peñimpenan (storehouse of the temple's relics). It in entered from middle zone via a gateway called kori aguṅ or paduraksa.

The designs of outer and middle zones are somewhat flexible. The slit drum pavillion can be built as outer corner tower. The temple kitchen can be located in outer zone instead.

Pura Maospahit in Denpasar is the only one to be constructed in Pañca-maṇḍala (5 zone) concept. This form of arrangement is similar to the ancient temples of Majapahit or to the kraton palaces of ancient Java.

→ Regular trimaṇḍala Balinese Temple Complex [Source: File:Bali temple diagram.png]

Types of temple complexes:

Type by presiding deity:

Pura Desa : Dedicated to Brahmā and local sprits. It is usually located in centre of a village and acts as the religious and cultural centre

Pura Puseh : Dedicated to Viṣṇu and human founders of the village. It is usually situated facing Bali’s most sacred and largest mountain, a stratovolcano named Mount Agung[1] (locally called Gunuṅ Aguṅ).

Pura Dalem : Dedicated to one or more of Śiva, Durgā, Kālī, Mother nature, Banaspatirāja (barong), Sang Bhuta Diyu, Sang Bhuta Garwa, and other deities. It is also common for a pura dalem to have a big tree like a banyan tree or a kepuh which is usually also used as a shrine. Pura Dalem is typically located next to the graveyard of the deceased prior to ṅaben (cremation) ceremony. It is also dubbed “Temple of the dead” and usually faces the sea.

Pura Mrajapati : Dedicated to Prajāpati (lord of people). Most often, in this temple, Shiva is worshipped in his form as prajapati.

Type by location:

Pura Segara (Sea Temple) : Located near the sea

Pura Tirta (Water temples) : temple complexes that along with religious function, also have water management function as part of Subak[2] irrigation system. The priests in these temple complexes have authority to manage the water allocation among rice paddies in the villages surrounding the complex. Some of such temples are noted for their sacred water and having petirtān or sacred bathing pool for cleansing ritual. Other water temples/temple complexes are built within lakes.

Pura Kahyaṅan Jagad or Pura Kahyaṅan Padma Bhuwana :

They are the 9 holiest places of worship on the island marking the 8 cardinal directions and center point. Built at strategic locations, they are meant to protect the island and its people from evil spirits. These temples belong to every Balinese on the island (as opposite to the other temples, which are the property of the village or town in which they sit).

Pura Besakih (in Karangasem Regency), the "mother temple" of Bali, for north-east direction.

Pura Lempuyang Luhur (half in Karangasem district and half in Abang district, Karangasem Regency), for east direction, associated with Iswara.

Pura Goa Lawah (in Pesinggahan district, Klungkung Regency), for south-east direction.

Pura Luhur Andakasa (in Antiga, Manggis, Klungkung Regency), for the south direction.

Pura Luhur Uluwatu (in Pecatu, Badung), for the south-west direction.

Pura Luhur Batukaru (in Tabanan), for the west direction.

Pura Pucak Mangu (in the village of Pelaga, Petang district, Badung Regency, on Mount Catur), for the north-west direction

Pura Ulun Danu Batur (in Kintamani), for the north direction. The name Ulun Danu means “head of the lake”; it is the abode of the deity Batari Ulun Danu, ruler of the lakes. This temple is also a Pura Tirta.

Pura Pusering Jagat (Pura Puser Tasik) (Pejeng, near Ubud, in Gianyar), for the center

Notable Temple Complexes

Pura Maospahit

Among the temples/temple complexes in Bali, Pura Maospahit[15] in Denpasar is the only one to be constructed in Pañca-maṇḍala (5 zone) concept. This form of arrangement is similar to the ancient temples of Majapahit or to the kraton palaces of ancient Java. Its history is recorded in Babad Wongayah Dalem, a stone inscription mentioning the story of Sri Kbo Iwa, an architect of Balinese religious architecture.

The first building of the complex is Candi Raras Maospahit, the main shrine of the complex, which was built in 1278 CE by Sri Kbo Iwa. In 1553 CE, another shrine, Candi Raras Majapahit was built besides the earlier shrine.

Zones of the temple complex:

1st zone — located to west of main shrine. Access is marked by a red-brick paduraksa known as Candi Kusuma. Contains the slit-drum tower.

2nd zone — located south of main shrine. Access is marked by a paduraksa known as Candi Reṅgat.

3rd zone (jaba sisi) — located to west of main shrine. Access is marked by a paduraksa known as Candi Rebah. Contains the kitchen

4th zone (jaba teṅah OR madya maṇḍala) — Accessed through a candi bentar via the east side of the 3rd zone. It was used to display sacred art which is only shown during festivals in Pura Maospahit. It is where several bale (Balinese pavilion) is located e.g. bale pesucian (purification pavilion), bale tajuk, and bale sumanggen.

5th zone (jero OR utamaniṅ maṇḍala) — contains the main shrine, and many other shrines dedicated to various deities.

→ Candi Maospahit:

Candi Bentar [Source: Pura Maospahit Denpasar, Denpasar Regency, Bali, Indonesia]

Candi Kusuma gate of eastern courtyard [Source: Pura Maospahit Denpasar, Denpasar Regency, Bali, Indonesia]

Bale Kulkul of eastern courtyard [Source: Pura Maospahit Denpasar, Denpasar Regency, Bali, Indonesia]

Kori Angung leading into the inner courtyard [Source: Pura Maospahit Denpasar, Denpasar Regency, Bali, Indonesia]

Bale Pangayunan (rear) and Bale Petirtan (front) [Source: Pura Maospahit Denpasar, Denpasar Regency, Bali, Indonesia]

Candi Raras Maospahit — the main shrine of the complex was its first building. (Built 13th century CE) [Source: File:Pura Maospahit Denpasar Bali.jpg]

Candi Raras Majapahit, a later twin of Candi Raras Maospahit built to its north (Built 1553 CE) [Source: Pura Maospahit Denpasar, Denpasar Regency, Bali, Indonesia]

Pelinggih shrines near the two innermost temples [Source: Pura Maospahit Denpasar, Denpasar Regency, Bali, Indonesia]

Footnotes

[2] Subak (irrigation) - Wikipedia

[4] Warmadewa dynasty - Wikipedia

[6] Goa Gajah, Gianyar Regency, Bali, Indonesia

[7] Goa Garba, Gianyar Regency, Bali, Indonesia

[15] Pura Maospahit - Wikipedia

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Balinese_architecture

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bhoma

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Leyak

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Padmasana_(shrine)

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Dang_Hyang_Nirartha